Trade Wars: Facts And Fallacies

Economics / Protectionism Oct 20, 2019 - 06:19 PM GMTBy: Steve_H_Hanke

U.S. President Donald Trump, alongside many others, has a straightforward view on international trade, particularly the U.S. external balance. They believe an external deficit is a malady caused by foreigners who manipulate exchange rates, impose tariff and non-tariff barriers, steal intellectual property, and engage in unfair trade practices. The president and his followers feel the U.S. is victimized by foreigners, as reflected in the country’s negative external balance.

U.S. President Donald Trump, alongside many others, has a straightforward view on international trade, particularly the U.S. external balance. They believe an external deficit is a malady caused by foreigners who manipulate exchange rates, impose tariff and non-tariff barriers, steal intellectual property, and engage in unfair trade practices. The president and his followers feel the U.S. is victimized by foreigners, as reflected in the country’s negative external balance.

This mercantilist view of international trade and external accounts is wrongheaded. The negative external balance in the U.S. is not a “problem,” nor is it caused by foreigners engaging in nefarious activities. The U.S.’s negative external balance, which the country has registered every year since 1975, is “made in the USA”—a result of its savings deficiency.

To view the external balance correctly, the focus should be on the domestic economy. The external balance is homegrown; it is produced by the relationship between domestic savings and domestic investment. Foreigners only come into the picture ‘through the backdoor’. Countries running external balance deficits must finance them by borrowing from countries running external balance surpluses.

It is the gap between a country’s savings (read: income, minus consumption) and domestic investment that drives and determines its external balance. This fact can easily be seen by studying the savings-investment identity:

CA = Sprivate – Iprivate + Spublic – Ipublic,

where CA is the current account balance, Sprivate is private savings, Iprivate is private domestic investment spending, Spublic is government savings, and Ipublic is government domestic investment spending. In this form, Sprivate – Iprivate is the savings-investment gap for the private sector and Sprivate– Ipublic is the savings-investment gap for the government sector. For a full derivation of the identity in this form, see “The Strange and Futile World of Trade Wars” by Steve H. Hanke and Edward Li in the Fall 2019 issue of the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance.

First, the national savings-investment gap determines the current account balance. Both the public and private sector contribute to the current account balance through their respective savings-investment gaps. The counterpart of the current account balance is the sum of the private savings-investment gap and public savings-investment gap (read: the public sector balance).

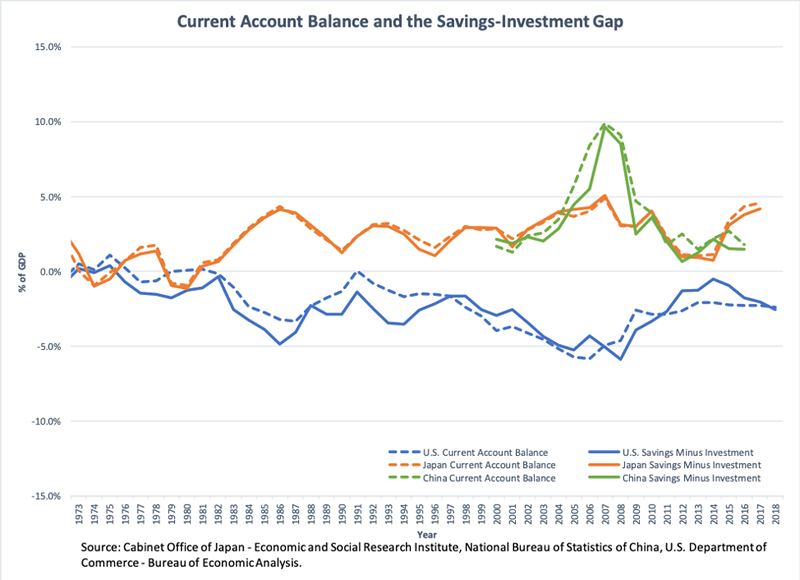

The U.S. external deficit, therefore, mirrors what is happening in the U.S. domestic economy. This holds true for any country, even those with significant external surpluses. The chart below, which comports with the savings-investment identity, makes this clear. The U.S. displays a savings deficiency and a negative current account balance that reflects its negative savings-investment gap. Japan and China display savings surpluses, and both run current account surpluses that mirror their positive savings-investment gaps.

Prof. Steve H. Hanke and Edward Li

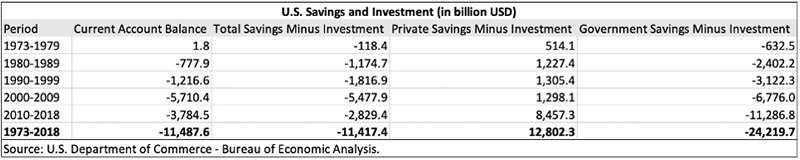

The table below shows again that U.S. data support the important savings-investment identity. The cumulative current account deficit the U.S. has racked up since 1973 is $11.488 trillion, and the amount by which total savings has fallen short of investment is $11.417 trillion. But, that is not the end of the story. Disaggregated U.S. data are available that allow us to calculate both the private and government contributions to the U.S. current account deficit. As shown in the table, the U.S. private sector generates a savings surplus—that is to say, private savings exceed private domestic investment—so it actually reduces (makes a negative contribution to) the current account deficit. The government stands in sharp contrast to the private sector, with the government accounting for a cumulative savings deficiency—that is to say, government domestic investment exceeds government savings, resulting in fiscal deficits—that is almost twice the size of the private sector surplus. Clearly, then, the U.S. current account deficit is driven by the government’s (federal, plus state and local) fiscal deficits. Without the large cumulative private sector surplus, the cumulative U.S. current account deficit since 1973 would be almost twice as large as the one that’s been recorded.

Prof. Steve H. Hanke and Edward Li

The straightforward implication of this analysis is that President Trump can bully countries he identifies as unfair traders and can impose all the restrictions on trading partners that his heart desires, but it won’t change the current account balance. The U.S. current account deficit is solely a function of the savings deficiency in the U.S., in which the government’s fiscal deficit is the proverbial elephant in the room. And how is the current account deficit financed?

Well, it turns out that foreigners who generate savings surpluses and current account surpluses finance the U.S. current account deficits. It is clear, therefore, that current account balances represent nothing more than a measure of the international trade in savings.

What’s more, the Trump administration’s fiscal policies, which promise ever-widening fiscal deficits, will throw a monkey-wrench into President Trump’s trade policy works. Indeed, if his fiscal deficits are not offset by an increase in private savings relative to private investment, increases in the federal budget deficit will translate into larger current account deficits. So, the U.S. current account deficit will not only continue to be made in the good old U.S.A., but it will be greatly enlarged by President Trump himself—the professed archenemy of external imbalances.

The good news, however, is that the U.S. has been able to finance its current account deficit with relative ease. Indeed, foreigners are more than willing to park their savings in U.S.-dollar-denominated assets. This is a tribute to the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency, America’s creditworthiness, and the effectiveness of U.S. corporate governance.

The level of economic illiteracy that surrounds the strange world of international trade policy is stunning. Now we have irrefutable arguments and evidence to explain why a country’s external balance is determined domestically, not by foreigners. As the history of trade policy shows, it’s difficult to change false beliefs with facts. But, now we have even more damning evidence to refute the false beliefs than ever before.

Follow me on Twitter. Check out my website.By Steve H. Hanke

www.cato.org/people/hanke.html

Twitter: @Steve_Hanke

Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics and Co-Director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Prof. Hanke is also a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C.; a Distinguished Professor at the Universitas Pelita Harapan in Jakarta, Indonesia; a Senior Advisor at the Renmin University of China’s International Monetary Research Institute in Beijing; a Special Counselor to the Center for Financial Stability in New York; a member of the National Bank of Kuwait’s International Advisory Board (chaired by Sir John Major); a member of the Financial Advisory Council of the United Arab Emirates; and a contributing editor at Globe Asia Magazine.

Copyright © 2019 Steve H. Hanke - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

Steve H. Hanke Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.