Bring on US Debt Default, Otherwise, it's Permanent Deficits and Unemployment

Economics / US Debt Dec 29, 2011 - 01:43 AM GMTBy: Gary_North

Throughout the West, unemployment remains stubbornly high. Unemployment in these European nations ranges from 8.5% in Italy to over 20% in Spain.

Throughout the West, unemployment remains stubbornly high. Unemployment in these European nations ranges from 8.5% in Italy to over 20% in Spain.

For Europe as a whole, the figure is 10.3%. What is revealing is this: ever since 1995, it has been above 9% most of the time. Only in February 2008 did it fall to 7.3%. For workers under age 25, the figures are much worse. A generation of educated college graduates has become a lost generation.

Yet as the chart reveals, a few countries are doing far better. Netherlands, Austria, and Germany have rates from about 4.5% to 6.5%. These are nations noted for their comparative frugality.

Yet as the chart reveals, a few countries are doing far better. Netherlands, Austria, and Germany have rates from about 4.5% to 6.5%. These are nations noted for their comparative frugality.

For Europe as a whole, it has been 40 years of unemployment. It the 1960s, European employment was high. This changed in the 1970s. Keynesian economists seem baffled by this. Keynesian policies of government deficits were supposed to end unemployment. They haven't in Europe.

The chart for the United States since 1965 is revealing. The unemployment rate climbs in recessions, then falls into the 4% to 6% range. Not this time. Since 2008, the rate has soared and has refused to come down. Use the interactive chart to select a base year.

All this is to say that the Keynesian system is unable to explain why unemployment should persist. The Keynesian tool kit has been available to national governments. The political leaders are disciples of Keynesianism. Their advisors are Keynesians. Yet the prescription is no longer working. The U.S. government has run three consecutive years of trillion-dollar-plus deficits. They have not worked to bring down the unemployment rate.

This raises a pair of questions. First, with respect to economic theory, why isn't the policy prescription working? Second, historical: When a theory ceases to explain events, why won't it be abandoned by a younger generation of theorists?

These two questions faced neo-classical economists in 1936. They could not answer either of them. They lost the war for the minds of the next generations.

KEYNES' REVOLUTION

In 1936, Macmillan published John Maynard Keynes' book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. The book was an attack on the free market's ability to clear itself of unsold goods, including "labor goods," by means of downward price adjustments.

The answer to this issue had been provided two years earlier in a book also published by Macmillan and written by the rising economic star, Lionel Robbins. Its title: The Great Depression. It was written from an Austrian School approach. Robbins had studied informally with Ludwig von Mises in Vienna. Keynes' question was answered again in 1937 by another book published by Macmillan, Banking and the Business Cycle, by three economists. It also was written from an Austrian outlook. So, the big winner in all this was Macmillan.

Keynes' book became dominant. Younger economists adopted it. The other two books were forgotten by 1940. Within two decades, the modified Keynesianism of Paul Samuelson was dominant in Anglo-American academia. It remains dominant today.

The heart of Keynes' thesis is this: downward price flexibility does not clear markets, including the capital goods markets. Classical economics had taught that the competitive pressures of the free market will lead to falling prices and decreased unemployment. The rule was this: "At a lower price, more is demanded." This includes labor.

The Great Depression by 1936 seemed to refute the classical economists' theory. Because this theory of causation was central to economics from Adam Smith to the Great Depression, the persisting unemployment seemed to refute this fundamental tenet of free market economic theory. Thus, the profession was waiting for a new theory of free market pricing. Keynes supplied this. The theory was wrong, but it had a ready market.

Keynes recommended what every Western government had been doing since 1930: run deficits. His solution was more of the same: larger deficits and more government employment.

The problem facing the West was what classical economists had argued against: tariffs that restricted trade and government-mandated domestic price floors that encouraged the production of goods that could not be sold at the legal prices. The U.S. government under Herbert Hoover ran unprecedented peacetime deficits. It restricted trade, both domestic and foreign. The story of this came late: Murray Rothbard's monograph, America's Great Depression (1963). It was ignored. The only major academic to pick it up was Paul Johnson, in his 1983 book, Modern Times. This section of his book has also been widely ignored.

The academic guilds in history, economics, and political science are committed to the ideal of fiat money. With the lone exception of Austrian School economists, fractional reserve banking is not merely accepted, it is actively promoted. So is central banking.

This unanimity is easy to explain. First, in a world dominated by government spending on education, he who pays the piper calls the tune. Tax money is the basis of formal education in the West. Formal education is compulsory through the teenage years. The teachers are required to be certified by government-policed accrediting institutions. The lure of money buys compliance. Those who go through the subsidized educational system generally believe in the legitimacy of the system.

The second reason for the widespread acceptance of Keynesianism is that Keynesian theory supports rule by certified economists. The economists dream of power and money, as do so many other graduates of tax-funded schools. This dream of getting in control over all that spending is irresistible to members of a class of guild-certified specialists to whom the supreme tool of power – money creation – is handed by the politicians.

Money is the central economic institution. It came as a result of market developments. The civil government took over the certification process. Then it demanded a monopoly of control. It has asserted this sovereignty over money creation for over two millennia.

In the field of money, there is no level playing field. It is tilted in favor of government. Thus, in the field of economic theory, the same tilting is visible.

Keynes' theory was tied more to fiscal policy – deficits – than to monetary policy. But from the beginning of modern central banking in 1694, with the Bank of England, there was a quid pro quo between the politicians and the private owners of central banks. In exchange for the monopoly over the money supply, the central bankers promise to provide sufficient money – newly created – to buy new issues of the national debt at below-market rates. In a world in which fractional reserve banking and central banking are universally accepted, the Keynesian policy of federal deficits inevitably leads to a defense of central banking money expansion. Keynesianism and central bank inflation are a package deal.

WORLD WAR II: WHY KEYNES WON

Keynsian policies had begun half a decade before Keynes' book appeared. They had not worked by 1936. They did not work in 1937, 1938, and most of 1939.

Then the war broke out. From that point on in the West, governments inflated. They all imposed price and wage controls. They all adopted rationing. Then they drafted tens of millions of working-age men to serve in the armed forces. This was repressed inflation on a scale never dreamed of in the West. Nothing like this had been seen since the Roman emperor Diocletian's reform in the early fourth century.

Repressed inflation creates demand. "When the price of anything is reduced, more is demanded." The legal prices of most new goods were reduced by government decree. Then the money supply was increased by government decree. So, there was an enormous demand for basic consumer goods. This demand could not legally be supplied by the controlled markets. So, the governments imposed rationing. The market principle of "high bid wins" could not be abolished, but it could be modified. The high legal bids were placed in the hands of those who had ration stamps. The high illegal bids often thwarted the central planners.

This general statement is true. "World War II solved the Great Depression." The problem is, this statement is not challenged by the economist's question: "At what price?" Government officials with guns told people where they could work and for how much. When people with badges are pointing guns at citizens, the government is capable of putting people back to work.

Keynesian economics did not overturn classical economics' theory of pricing. Keynesianism was the historical outcome of a government-decreed system of price floors. Monetary deflation coupled with wage and price rigidities did produce unemployment on a massive scale. It did not go away, because the policies did not go away. "Too many goods chasing too little money at government-mandated prices."

Keynesian economics also did not overturn classical economics' theory of pricing during World War II. The governments inflated massively and imposed price ceilings. Demand rose. Supplies fell. Goods could not easily be obtained. "Too much money chasing too few goods at government-mandated prices."

The Great Depression was the product of bankrupt fractional reserve banks, which shrank the money supply when they failed. To this was added government-imposed price floors. People were offered goods to buy, but there was not enough money to buy them at the above-market mandated prices. Result: reduced wealth.

The Great War was funded by fractional reserve banks, which increased the money supply when central banks bought government debt. To this was added government-imposed price ceilings. People had money to spend, but not enough consumer goods to buy them. Ration coupons eliminated legal market demand, but this led to black market prices, which siphoned goods away from law-abiding people. Result: not enough goods to meet market demand. Result: reduced wealth.

So, government intervention, 1930-39, reduced wealth. Government intervention, 1939-45, also reduced wealth for those who were not killed. Worldwide, about 60 million were killed. This reduced production even further.

Why did Keynes win the intellectual battle? Because the masses did not want to believe that the Great Depression and World War II had been avoidable. A privately created gold coin standard plus the enforcement of contracts would have presented both of these events. People did not want to believe that government policies brought such misery. They had been taught that government heals. They had been taught a messianic view of the state. They were not ready to break with the supposed source of safety in an economic downturn.

They still aren't.

Economists have been unwilling to abandon the chief premise of Keynes, namely, that government deficits can mitigate and then overcome recessions. This premise rests on an assumption: there is a class of specially trained experts who can successfully oversee the process of deficit spending, so as to avoid either crowding out of capital in the private sector or the pop-gun effect of insufficiently large deficits.

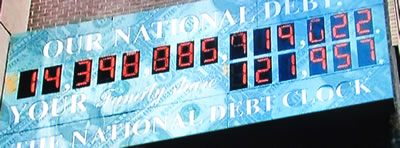

TRILLIONS AND TRILLIONS

The tools in the Keynesians' tool kit have failed to overcome unemployment in the U.S. since 2008. Massive deficits have not worked. Central bank inflation has not worked. These are the twin pillars of Samuelson's neo-Keynesian synthesis.

All Keynesians call for patience. That was what neo-classical economists called for in the 1930s. At some point, everyone lost patience. Some Keynesians call for larger deficits. But more of the same hastens the day of reckoning when private investors refuse to lend more money at today's low rates. Then what?

The economy is dependent on government spending. People receive their checks. They need those checks to maintain their present lifestyle. They greatly fear losing these checks.

Today, we are told by Keynesians and their fellow travelers that the government should not reduce spending. Why not? Because this would supposedly exacerbate the recession.

It would not exacerbate the recession. It would increase unemployment. The two outcomes are different.

Consider unemployment. Spending by the government crowds out spending by those who were either taxed or who lent the government money. When taxpayers are allowed to keep their money, their pattern of expenditures will change. They will re-budget. It will take time for this new demand to register in the thinking of entrepreneurs. In the meantime, those no longer receiving checks will have to readjust. There will be added unemployment until these now highly motivated people adjust. "You can't spend it if you ain't got it."

This is not part of the recession. It is part of the overcoming of recession. This rising unemployment will be added to the existing figures but this will not last. Without the welfare checks, people will find employment. It may take them time. They will have to lower their wage demands. But, at some low price, the markets will clear. They clear on the stock exchanges. They clear on the bond exchanges. They will clear in the labor exchanges.

No one in Washington wants the political effects of reduced government spending. Yes, unemployment will rise. It will take time for those who received government money to find new sources of revenue. But this does not mean that the money will not be spent. Others will retain the money that Washington did not spend.

Keynesianism rests on a grand deception. It argues that government spending can get the market rolling, whereas spending by private citizens cannot. This makes no sense. Spending is spending.

The deficits will not end, because the politicians do not want to cut spending. The Keynesians have built their careers and their self-confidence on the assumption that any reduction of government spending in a recession will make the recession worse. Yes, reduced spending by the government will make unemployment worse until people who lose their bailouts reduce spending. This will not make the recession worse. It will reduce the bottlenecks on production.

CONCLUSION

The deficits are permanent. High unemployment is also permanent. The Keynesian prescription will not make the patient well. It will make him sicker.

There will come a day when Keynesians will no longer be able to sell their patent medicine to opinion leaders. There will be a Great Reversal of opinion. I think this will come in the aftermath of the Great Default by national governments. That default is coming.

Gary North [send him mail ] is the author of Mises on Money . Visit http://www.garynorth.com . He is also the author of a free 20-volume series, An Economic Commentary on the Bible .

© 2011 Copyright Gary North / LewRockwell.com - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.