U.S. Debt Explosion Sets in Motion Massive Revolutionary Changes

Economics / US Debt Nov 09, 2009 - 09:15 AM GMTBy: Martin_D_Weiss

I’ve just returned from Munich, Germany, where Claus Vogt and I addressed the 8th Annual Conference of Sicheres Geld subscribers.

I’ve just returned from Munich, Germany, where Claus Vogt and I addressed the 8th Annual Conference of Sicheres Geld subscribers.

Here are the highlights of my side of the presentation. (Claus will give you his side in a future issue).

Massive Revolutionary Changes

A few years ago, when we first began this journey together, we warned that the U.S. government was leading us to a future banking panic.

We warned about the housing bubble that was about to burst.

We told you about the giant monster of derivatives that could someday explode.

And we showed you how the U.S. real estate bust and the derivatives monster were likely to strike the largest financial institutions of Wall Street, threatening a meltdown in global financial markets.

Then, three years ago, we described the coming crisis in greater detail, naming the large financial institutions we believed were most likely to fail:

- Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, two of America’s largest investment banks

- Countrywide Financial and Fannie Mae, America’s largest mortgage lenders

- Washington Mutual, America’s largest savings and loan corporation

- Citigroup, America’s largest consumer ban

Virtually no one believed this was possible.

When we gave the story of the Citigroup failure to a reporter of a major business magazine, the editor nixed the story. When we told other banking experts that Citigroup was on the brink of failure, they laughed. When we told government officials, the company executives simply told them we were crazy.

As it turned out, the crisis was not less severe than we expected. Nor was it as severe as expected. Rather, the crisis was actually more severe — for two reasons.

First, in addition to the companies that we named as candidates for failure, several other giant companies that we had not named also went bankrupt or required a bailout.

The failed Wall Street firms included not only Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, but also Merrill Lynch.

The failed commercial banks included not only Citigroup, but also Bank of America.

The bankrupt institutions were not only in the U.S., but also in the U.K., Germany, and even Switzerland — Royal Bank of Scotland; IKB and Hypo Real Estate in Germany; and UBS in Switzerland.

They included not only banks and brokerage firms, but also the largest single insurance company in America, AIG.

But whether we named them ahead of time or not, the salient fact is that, in nearly every major financial industry — commercial banking, investment banking, consumer banking, brokerage, mortgage lending, and insurance — the companies that failed, or almost failed, were not small- or medium-sized. They weren’t the third largest or fourth largest. They were the single largest in the world.

Think about that: The world’s largest companies in every single sector of the financial industry. Failed. Bankrupt.

Now, fast-forward to today, November 7, 2009. Suddenly and miraculously, the same economists who told you this crisis could never happen are now telling you that this crisis is “over.” And the same government officials who scoffed at the notion of giant financial failures are claiming they have the final solution to those failures.

But the derivatives we warned you about are not gone. They are still there. Nor are the bad debts on the books of major banks. And most important, the government policies which created the crisis in the first place have not been modified or reduced. They have actually been accelerated, as we’ll demonstrate in a moment.

And therein lies the second reason the crisis is actually worse than we expected. With its deliberate policies, the U.S. government, along with governments here in Europe, have now transformed the Wall Street debt crisis into the Washington debt crisis.

They have transformed a crisis that was bankrupting individual institutions into a crisis that could threaten to bankrupt sovereign governments. Worst of all, they have converted a crisis of debt into a crisis of our currency.

|

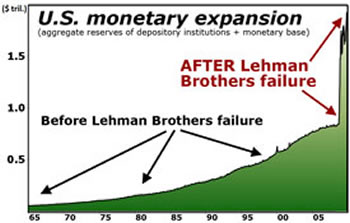

This chart shows the monetary base of the United States. It represents the most basic form of money supply — cash currency in the coffers of U.S. banks plus their total reserves.

As long as this basic measure of money supply is growing at a moderate pace, you can generally expect stability in the U.S. dollar, gold, and other markets. There will be ups and downs, of course, and sometimes, due to other global events, those ups and downs could be sharp. But they will not turn the world upside down.

Indeed, this had been the pattern since World War II: relatively moderate expansion. Up until September of last year, when Lehman Brothers failed, it took the U.S. Federal Reserve a total of 5,012 days to double this measure.

But then, look what happened: Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke doubled the U.S. monetary base in 112 days. Not in 5,012 days as his predecessors had done — but in a meager 112 days! He accelerated the pace of bank reserve expansion by a factor of 45 to 1.

Imagine a crowded highway with most cars traveling at an average speed of 100 km per hour. Then imagine a new driver appearing on the scene with a jet-powered engine that accelerates to a supersonic speed of 4,500 km per hour. That’s the same magnitude of change Fed Chairman Bernanke has presided over.

Ladies and gentlemen, this is not just more of the same trend that we have witnessed over the decades. It’s a massive, revolutionary change in the entire structure of the U.S. economy.

Even in the most extreme circumstances of history, the Fed never pumped in this much money in such a short period of time.

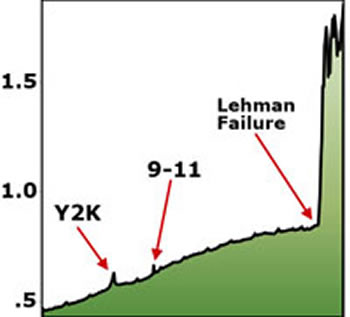

For example, before the turn of the millennium, the Fed was afraid of a computer catastrophe at the banks caused by the widely publicized Y2K bug. So it rushed to provide liquidity to U.S. banks and increased the monetary base by $73 billion in three months. At the time, that was considered huge. But this time, Mr. Bernanke has increased the monetary base by over $1 trillion, or 14 times more!

|

Here’s another example: In the days following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the Federal Reserve rushed to flood the banks with liquid funds. That time, it added $40 billion in less than 14 days. However, Mr. Bernanke’s recent trillion-dollar deluge of money is twenty five times larger.

Here’s the most astounding fact of all: After the Y2K and 9/11 crises had passed, the Fed promptly reversed its money infusions. It pulled out the extra liquidity from the banking system.

|

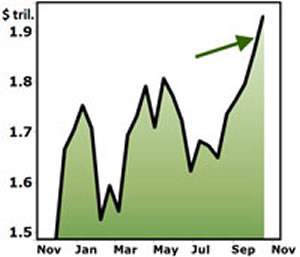

But this time, Mr. Bernanke has done precisely the opposite. Since he doubled the currency and reserves at the nation’s banks with his 112-day money-printing frenzy in late 2008, he has thrown still more money into the pot. And late last month, the monetary base surged to new, all-time highs.

Ladies and gentlemen, this is not just more of the same trend that we have witnessed over the decades. It’s a massive, revolutionary change in the entire structure of the U.S. economy.

This is the elephant in the room — the situation that everyone knows is there, but no one wants to admit.

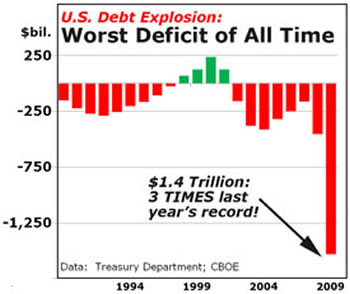

Now, let’s take a look at this same elephant from another perspective — the largest federal budget deficits in the history of mankind.

If the U.S. federal deficit were growing by 20 percent, 30 percent, or even as much as 50 percent, the pundits could have argued that it was just the continuation of a long-term trend, that it was simply more of the same.

|

But just in the last 12 months, the U.S. federal deficit has exploded from $454.8 billion in fiscal 2008 to $1.4 trillion in fiscal 2009. It has tripled in size in just one year’s time.

I repeat: This is not just more of the same trend that we have witnessed over the decades. It’s a massive, revolutionary change in the entire structure of the U.S. economy … and it’s totally unprecedented in history.

Now let’s turn to the consequences of these events — first, the intended consequences and then some of the unintended consequences.

Consequence #1 is a recovery in the U.S. economy. When the government creates that much monetary and fiscal stimulus, it naturally has some impact, of course. That’s why a recovery is now under way and why it is likely to continue for a few more quarters.

Consequence #2 is the rally in the U.S. stock market. Again, when so much liquidity is pumped into the economy, it’s only natural that some of it would flow into equities.

Consequence #3 is a recovery in emerging markets. Here, unlike the U.S. and other Western economies, not only are the economies benefiting from government stimulus, but they are also benefiting from strong domestic fundamental growth factors.

Consequence #4 is the decline of the U.S. dollar. The greenback is falling against the euro and virtually every major currency on the planet, and it will probably continue to do so. The U.S. Dollar Index, which measures the dollar against a basket of six major currencies, is now nearing its lowest level in history. Once that level breaks, the pace of the dollar’s decline could accelerate sharply.

Consequence #5 is the decline in the value of paper money as a whole, and the parallel rise in gold. Friday, gold pierced the $1,100 per-ounce level. Next, despite any intermediate setbacks, it could rise to $1,300.

Consequence #6 is rising interest rates. Yes, the Federal Reserve can hold its official short-term interest rates near zero, and this is precisely what it’s doing. But the Fed does not exert the same control over long-term interest rates. Nor can it control foreign central banks, some of which are beginning to raise interest rates. And most important, the U.S. government cannot control foreign investors who now own over half of the publicly traded U.S. government securities.

Meanwhile, the forces driving long-term interest rates higher are powerful and enormous — the same forces we told you about earlier: massive monetary inflation and equally massive federal deficits.

Consequence #7 is an anemic U.S. economy overall, weighed down by high unemployment, low spending, and most important, the largest debts of all time. Don’t expect this recovery to last very long. A second recession could come quickly on its heels.

I am often asked: Is the recession over? My answer is “yes.” But to the more important question — is America’s long-term depression over? — my answer is a firm “no.” In the years ahead, we’re likely to see a series of longer-than-usual recessions interrupted by shorter-than-normal recoveries, all adding up to a long depression.

Such is the inevitable consequence of the massive, revolutionary changes that have already taken place … with more changes of similar magnitude still ahead.

This investment news is brought to you by Money and Markets . Money and Markets is a free daily investment newsletter from Martin D. Weiss and Weiss Research analysts offering the latest investing news and financial insights for the stock market, including tips and advice on investing in gold, energy and oil. Dr. Weiss is a leader in the fields of investing, interest rates, financial safety and economic forecasting. To view archives or subscribe, visit http://www.moneyandmarkets.com .

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.