Bailout for the People: Dividend Economics and the Basic Income Guarantee

Politics / Credit Crisis Bailouts Feb 04, 2009 - 08:29 AM GMTBy: Richard_C_Cook

Prepared for a Presentation at the 8 th Congress of the U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network and 2009 Eastern Economics Association Annual Conference Sheraton New York Hotel and Towers New York, N.Y., February 27

Prepared for a Presentation at the 8 th Congress of the U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network and 2009 Eastern Economics Association Annual Conference Sheraton New York Hotel and Towers New York, N.Y., February 27

The existing monetary system is not free enterprise, and it is not capitalism. It is cancer.

Isn't it Finally Time to Enact a Basic Income Guarantee?

The lack of individual and family income security in the midst of a highly-developed economy is a travesty under any circumstances. But the contradiction of “poverty in the midst of plenty” that has plagued the world since the start of the Industrial Revolution is becoming much more grave in the U.S. and abroad as the recession of 2008-9 worsens.

The problem does not lie with the production of goods and services which technology can accomplish abundantly. The problem lies with the distribution side of the equation. What people increasingly lack today is the money to purchase the necessities of life. Both the workplace and capital are idled because employees and consumers lack the purchasing power to buy the products and services our economy is capable of producing. The basic problem is excess capacity relative to available income.

The problem does not lie with the production of goods and services which technology can accomplish abundantly. The problem lies with the distribution side of the equation. What people increasingly lack today is the money to purchase the necessities of life. Both the workplace and capital are idled because employees and consumers lack the purchasing power to buy the products and services our economy is capable of producing. The basic problem is excess capacity relative to available income.

Winston Churchill gave eloquent testimony to this conundrum of the modern age when delivering the Romanes Lecture at Oxford University on June 19, 1930. This was a few months after the crash of the U.S. stock market marked the start of the Great Depression. Churchill said:

“Who would have thought that it would be easier to produce by toil and skill all the most necessary or desirable commodities than it is to find consumers for them? Who would have thought that cheap and abundant supplies of all the basic commodities would find the science and civilization of the world unable to utilize them? Have all our triumphs of research and organization bequeathed us only a new punishment: the Curse of Plenty? Are we really to believe that no better adjustment can be made between supply and demand? Yet the fact remains that every attempt has failed. Many various attempts have been made, from the extremes of Communism in Russia to the extremes of Capitalism in the United States. They include every form of fiscal policy and currency policy. But all have failed, and we have advanced little further in this quest than in barbaric times. Surely it is this mysterious crack and fissure at the basis of all our arrangements and apparatus upon which the keenest minds throughout the world should be concentrated.

Evidently we've learned little since Churchill spoke. Isn't it shameful—or just surprising—that since the proponents of “post-modern” economics restructured the U.S. economy around the concept of a deregulated financial sector over the past 30 years, income and wealth disparities between rich and poor have become much worse? Thus the ability of even middle-class people to pay for such basic needs as housing, food, medical care, and transportation falls ever further behind.

Perhaps we are finally ready to reopen the question of whether human beings have the right to an income sufficient to keep body and soul together even during difficult times. Within the U.S., this question has been mostly lost since President Ronald Reagan declared in his 1981 inaugural address that, “Government is not the solution to the problem; government is the problem.”

For it is only government that can authorize and implement what is called a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG). But if government is trapped in the ideological straightjacket Reagan and his fellow conservatives put it in, then the only possible outcome is Social Darwinism—i.e., survival of the fittest. We shouldn't sugar-coat the pill. Social Darwinism is a death sentence for those unable or unwilling to claw their way to the top. Obviously voters repudiated this philosophy by the election of Barack Obama as president of the U.S. last November. Therefore the debate over implementation of a BIG that was abandoned over a generation ago should now also be reopened.

BIG Reconsidered

It is not difficult to see that implementation of a Basic Income Guarantee, had it been put in place when the concept still had political life in the U.S. during the 1960s and early 1970s, would have gone a long way toward ameliorating human distress from poverty along with assuring a significant degree of economic justice. And the population as a whole would clearly be much better off today, when loss of a job usually creates a family financial calamity, often with cancellation of health insurance and the risk of home foreclosure.

The last serious efforts at a BIG were President Richard Nixon's Family Assistance Plan, which passed the House but was defeated in the Senate in 1970, and implementation of the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income families, enacted in 1975 and extended by President Bill Clinton in the 1990s. Since the 1970s, almost every step toward economic “reform” has been one permutation or another of trickle-down economics, including the supply-side tax cuts of the Reagan and Bush II administrations.

Of course, the move to deregulate the financial industry that has been going on for three decades, along with the tax cuts for the upper brackets that characterized the supply-side approach, were supposed to have created a new “ownership” society based on having our money “work for us.” But the bubble economy that resulted from deregulation has now blown up, exposed as the biggest financial fraud in history. It is true that many more people now participate in the financial markets through mutual funds and 401(k) plans, but the value of these portfolios is ravaged during financial downturns like the one today.

Yet even in the midst of massive government bailouts for the banks and the as-yet-to-be-implemented economic stimulus proposals for the people, a BIG is never mentioned, not even by progressives. One problem with BIG is that its proponents often presented it as a transfer-of-wealth program, where a portion of the earnings of people with earned incomes would be diverted through taxation to support those in need. Even the idea of reducing military expenditures to support a BIG could be viewed as a transfer program, since a smaller war machine would mean a reduction of salary and benefit payments to military personnel and civilian contractors.

At times, some of those in favor of BIG have seemed to view it almost as a kind of charity. Others have pointed to a stronger moral grounding based on the fact that it is the whole of society that provides the vital ingredients for enterprises to be successful.

Bill Gates, for instance, could never have earned billions on his own. He depended on complementary industries, such as semiconductors, as well as an educated workforce, competent consumers, a strong patent and legal system, the transportation and retail infrastructure, etc. If it was society that provided such things, then society has a legitimate claim to sharing the proceeds based on its contributions.

One way the larger social contribution is acknowledged is through government's claim on sharing the profits of enterprise through taxation. But taxation also is a burden that adds to the cost of products. Viewed simply as an additional cost, it is likely safe to say that a BIG has little, if any, chance to be implemented within the U.S. at any time in the foreseeable future, at least in an amount that would have an impact. In time of recession in particular, no one has the political appetite to argue in favor of a more equitable distribution of a dramatically shrinking economic pie.

But there are other ways to look at the problem. One is that of the Social Credit movement, where a regular dividend payment to individuals is seen not only as fair but is viewed as a necessary balancing force within a developed economy. A dividend in this case refers to a payment to all members of society based on the productive potential of the economy, not on tax revenues or government borrowing. But Social Credit concepts, while a force in the British Commonwealth nations, is virtually unknown in the U.S. Closer to home is the Alaska Permanent Fund (APF), where residents enjoy by right a share of the resource wealth of the state.

Both Social Credit and the APF as models for action will be discussed in this paper. The paper focuses on the U.S., though the concepts are applicable worldwide, and proposes a method of providing a BIG as part of a program to rebuild the economy from the bottom up. I call this program, based on dividend-type approaches, a “Bailout for the People,” as opposed to the bank bailouts that are adding trillions of dollars to the national debt and failing to revitalize the economy. I have presented this program previously in articles on the internet as “The Cook Plan.” (See “ How to Save the U.S. Economy ,” Market Oracle, October 10, 2008)

A Historic Collapse

As the recession deepens, with precipitous declines in employment, business activity, home appraisals, consumer confidence, and retail sales, it is evident that the U.S. and the world could be facing the possibility of an economic collapse of Great Depression severity. Officialdom denies it, but they also denied the recession was here until almost a year after the fact. Meanwhile, violent crime, stress-caused illness, and tension among nations are increasing.

Amazingly, it took a full year of economic distress, from December 2007, when economic activity last peaked, to a conference call on November 28, 2008, before the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research declared that a recession had actually been taking place. As late as September 15, 2008, Republican presidential candidate John McCain said, “the fundamentals of our economy are strong,” a statement that mirrored what President George W. Bush had been intoning ever since the housing bubble began its rapid deflation in 2006.

But even with the economists and politicians finally acknowledging reality—it was the recession that propelled Barack Obama to victory—the situation is actually worse than they say. If economic health is measured, for instance, by immediate consumer purchasing power, it is telling that M1—the money in cash and checking accounts—has been decreasing, when adjusted for inflation, since December 2003. That was five years ago!

The decrease began soon after the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates following three years of cuts—over 500 basis points—that created the housing bubble in the first place. The bubble was the method chosen by the Bush administration and Federal Reserve to act as an economic engine after the recession of 2000-2001. Naturally, when they stopped inflating the bubble, cash-on-hand began to decline.

The recession is now settling in. The official unemployment rate was 7.2 percent at the end of December 2008, with half a million jobs disappearing per month. Major corporations in the retail, heavy equipment, and technology sectors—like Home Depot, Caterpillar, and Sprint—are shedding jobs by the thousands. So are the financial institutions that had grown so much they produced over $500 billion in profits as late as 2006.

Some commentators are predicting an unemployment rate of more than 10 percent within the next couple of months. Additionally, the number of underemployed or no longer seeking jobs is likely running at rate similar to the number officially out-of-work. According to John Williams' Shadowstats website, unemployment including “discouraged workers” is almost 18 percent. Thus total unemployment could soon top 20 percent—close to Great Depression crisis conditions. Mere unemployment benefits cannot keep pace with this type of emergency.

Hence the action of the Obama administration to implement a major economic stimulus package. But will such a stimulus make a big enough difference? Can it be implemented in time? According to a January 26, 2009, report of the Congressional Budget Office, two-thirds of the proposed measures would be in place by September 2010, producing a “noticeable impact on economic growth and employment.” “Noticeable impact?” Is that good enough for a national and international crisis?

The fiscal reality is such that the federal government is poorly equipped to step in. The George W. Bush administration long ago reversed the Clinton budget surpluses by cutting taxes for the rich and through the enormous costs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

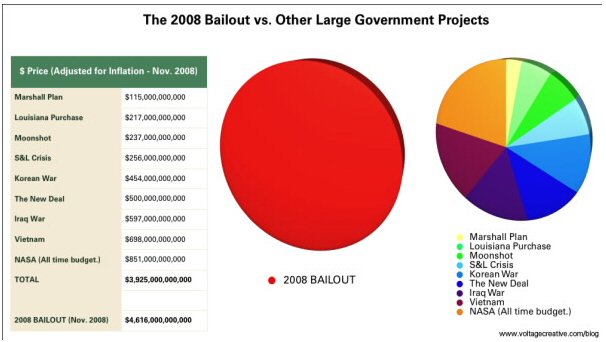

The federal budget deficit was added to significantly during the last six months of the Bush administration by former Secretary of the Treasury Paulson's $700 billion financial industry bailout, along with other loans and bailouts to rescue Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, insurance giant AIG, and additional emergency loans to banks and businesses from the Federal Reserve under Chairman Ben Bernanke. No one really has a handle on how much government money has been committed. $4+ trillion is a reasonable guess, though some estimates go as high as $8.3 trillion. The size of the bailout compared to government spending for major projects in history is shown in detail in the following graphic by www.voltagecreative.com/blog .

Still to come are any loans Congress or the Treasury will end up authorizing to save the auto industry and the costs of President Obama's economic stimulus package that may approach $1 trillion. More bank bailouts may also be needed. According to Jonathan Macey of Yale University, author of a book about a bailout of Sweden's banking system during the 1990s, “The pace of …bank losses is outrunning the infusions by the government.” Projections of more financial industry bailouts have been made by Vice President Joe Biden and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac may need an additional $16 billion.

During the coming two to three years the ratio of the national debt to GDP, which peaked at 125% in 1945, will likely exceed that record amount. The value of such a calculation is that it is transparent to inflation and may conveniently be compared to individuals in the same financial straits. What would happen to a family that each year incurred new debt at a rate of 125% of what they earned?

The difference between now and 1945 is that at the end of World War II American consumers enjoyed a high rate of savings due to full employment during the war, combined with a dearth of available consumer goods. After the war, these savings became available for the economic growth that paid down the national debt and created the boom of the 1950s. Today, consumer savings are virtually non-existent. And there is no assurance that more government spending will achieve anything like the full employment of the World War II era.

So the nation in 2009 is in uncharted territory, a scenario that is being repeated around the world with increased poverty, the decline of economic growth even in explosive economies like those of China and India, and imposition of more government austerities on less-developed nations by the International Monetary Fund. Again, under such circumstances, a Basic Income Guarantee, were anyone to consider it here or elsewhere, cannot be a simple transfer program, where those still with money are required to share a significant portion of it with those without. Rather new methods of funding must be found.

The Failure of Economics

So what is really wrong with the economy? Some say the housing bubble is the culprit, where the banks made credit so easy to acquire that the prices of homes inflated beyond their real value. Others point to the “toxic debt” from subprime mortgages that investment banks packaged and sold to unwary investors in tranches of mortgage-backed securities. Others blame the unregulated U.S. financial system which generated huge amounts of speculative investments, accomplished through bank leveraging, that now have gone sour. Here's what economist Joseph Stiglitz wrote recently in Vanity Fair :

“Of course, the current problems with our financial system are not solely the result of bad lending. The banks have made mega-bets with one another through complicated instruments such as derivatives, credit-default swaps, and so forth. With these, one party pays another if certain events happen—for instance, if Bear Stearns goes bankrupt, or if the dollar soars. These instruments were originally created to help manage risk, but they can also be used to gamble. Thus, if you felt confident that the dollar was going to fall, you could make a big bet accordingly, and if the dollar indeed fell, your profits would soar. The problem is that, with this complicated intertwining of bets of great magnitude, no one could be sure of the financial position of anyone else—or even of one's own position. Not surprisingly, the credit markets froze.”

Stiglitz is a former World Bank chief economist, a Nobel Prize winner, and professor at Columbia University. What is puzzling is his apparent lack of recognition of the role of collapsing consumer purchasing power as a cause of the freezing of the markets.

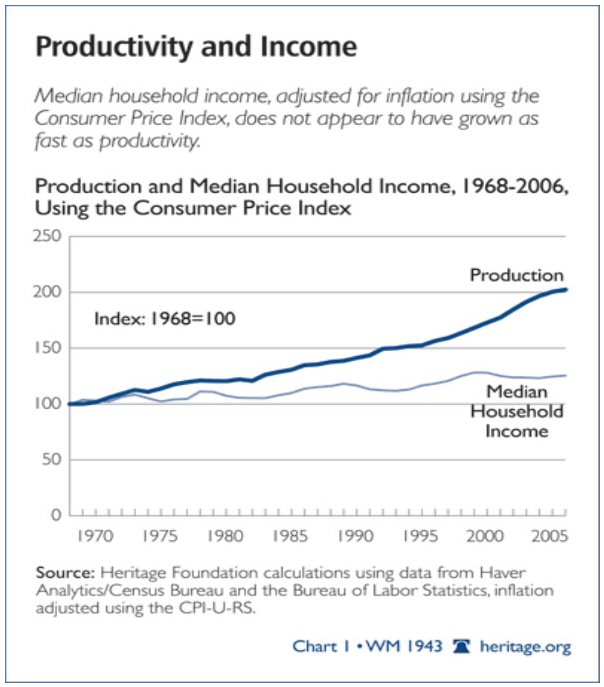

The following chart from www.Heritage.org compares growth in productivity to median household income within the U.S. over almost 40 years:

It is not difficult to see that individuals can no longer get loans because of the simple fact that they can't afford to repay them . Businesses can't get loans because declining consumer income is insufficient to buy their products. Within the U.S., consumer purchasing power has fallen not only because of the outsourcing of so many manufacturing jobs to low-paying overseas labor markets like China, but also because workers have not shared in the benefits of rising productivity.

As stated, for commentators like Stiglitz, or like Paul Krugman, another Nobel Prize winner who teaches at Princeton and writes for the New York Times , the debt-based monetary system run by the banks is a “given” as the unchallenged centerpiece of the world economy. But every debt a bank originates has to be paid, sooner or later, and paid with interest. The day of reckoning can be put off for a while by fresh lending, but not forever. If debt chronically outpaces earnings, the system will collapse.

Here is Krugman's prescription from a November 18, 2008, column:

“What the world needs right now is a rescue operation. The global credit system is in a state of paralysis, and a global slump is building momentum as I write this. Reform of the weaknesses that made this crisis possible is essential, but it can wait a little while. First, we need to deal with the clear and present danger. To do this, policymakers around the world need to do two things: get credit flowing again and prop up spending.”

But even as Krugman and others argue for more government spending to prime the economic pump and restore employment—another trillion dollars added to the national debt can't hurt, they say—such spending can only take place through more Treasury borrowing funneled through the Federal Reserve System. So their answer to a crisis marked by overwhelming public and private debt is more debt. This is where over-reliance on Keynesian economics has led. As Richard Nixon famously said back in 1971, “We are all Keynesians now.” It's still the case in 2009.

The problem is that the world has changed radically since John Maynard Keynes wrote in the 1930s at a time when the banking system had discredited itself with the economic collapse that started the Great Depression. Then, the banks were contracting the currency and causing a liquidity shortage. But they were brought to heel by the federal government under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. To get things moving again, the government ran its own low-cost credit programs through agencies like the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. And while the government borrowed for job-creation programs like the WPA and CCC, business and household debt weren't even close to what they are today.

What has happened since then is that the full-employment industrial state that was brought into existence in the U.S. by the New Deal and World War II, and which produced so much wealth that a BIG—then defined as a negative income tax—actually was taken seriously as a matter of discussion in the 1960s, no longer exists. Instead of the industrial state, we have what should be called the international “Empire of Usury.”

Road to Disaster

By the late 1960s the U.S. industrial state was being replaced by global outsourcing of manufacturing overseen by the financiers at the head of the largest American banks. Export of manufacturing operations to cheaper labor markets served a dual purpose: costs were reduced and payment of U.S. taxes by corporations could be avoided. A key event took place in 1971 when President Nixon removed the gold peg from the dollar and world currencies began to float. From that point on, credit became separated from production, and people began to look more to paper profits through currency, resource, and asset speculation as the source of wealth.

From 1971 onward, the financial magnates, located mainly in the U.S. and Britain, regularly made greater profits in currency trading and capital gains from asset inflation than in the production of goods and services. Who needed workers any more? Plus the U.S. was able to assure that the dollar would become the permanent world reserve currency by making it the standard for petroleum sales.

During the early 1970s, once removal of the gold peg made the quantity of dollars infinitely expandable, the U.S. government actively encouraged OPEC to implement radical increases in petroleum prices. The flood of “petrodollars” which resulted were deposited by the oil producers in U.S. banks or used to buy Treasury bonds. This money financed the growing U.S. trade and fiscal deficits and caused a sharp rise in inflation due in part to a devalued American currency. When the Federal Reserve under Chairman Paul Volcker began to attack the inflation with interest rates that would exceed 20 percent, the worst recession since the Great Depression followed.

This recession lasted from 1979-83 and wrecked the U.S. industrial economy. Never before in U.S. history had the financiers wielded such dictatorial—and destructive—power. The focal point of this power was David Rockefeller's Chase Manhattan Bank. The revolving door between Chase and the U.S. government is illustrated by Volcker's career.

Volcker began in 1952 as a Federal Reserve economist after being educated at Yale, Harvard, and the London School of Economics. He joined Chase as a financial economist in 1957. In 1962 he left for the U.S. Treasury Department and served as director of financial analysis. His boss was Rockefeller protégé Douglas Dillon, President John F. Kennedy's Secretary of the Treasury. In 1963 Volcker became deputy under-secretary for monetary affairs.

In 1965 he returned to Chase as vice president and director of planning before heading back to Treasury in 1969 to spearhead the removal of gold convertibility. While still at Treasury, he became a founding member of David Rockefeller's Trilateral Commission.

Then in 1975 Volcker became president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and was appointed to the Fed chairmanship in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter. Today Volcker is 81 years old. Now this quintessential Rockefeller technocrat is back as an adviser to President Barack Obama and head of the President's Economic Recovery Advisory Board.

The last straw in the destruction of the U.S. as an industrialized democracy came when the financial industry began to be deregulated during the late 1970s to take advantage of the orgy of greed that had been made possible by government monetary policy. The bankers and multinationals didn't care, because much of the U.S. trade deficit resulted from corporations buying from their own overseas subsidiaries whose products were then sold to American consumers on credit.

Accordingly, every period of domestic economic growth since then has been a financial bubble, including the merger-acquisition bubble of the Reagan/Bush I years, the dot.com bubble of the 1990s while Bill Clinton was president, and the housing/equity/derivative bubble of the 2000s during the George W. Bush administration. Each bubble was initiated by Federal Reserve interest rates cuts. Each was financed by massive bank lending, combined with foreign investment in the securities markets and tangible assets like real estate.

Every president since Reagan made his own contributions to the madness of financial deregulation. Meanwhile, the loss of manufacturing jobs that had started in the late 1960s and accelerated during the Volcker recession continued under President Bill Clinton, who signed NAFTA and gave China most-favored-nation status. The number of manufacturing jobs declined further under President George W. Bush.

Another feature of the bubble economy, especially during the 2000s, has been that growth, such as it was, has been tied to real estate through waves of construction for vast suburban tracts of new homes, retail mega-stores, upscale urban shopping/apartment/condo complexes, and gigantic new office buildings spread across the landscape as far as the eye could see. Industrial areas of former years were either converted to these uses or abandoned.

The retail stores are owned by the gigantic global conglomerates, sell mainly goods produced in China and other cheap labor markets, and employ low-paid domestic and immigrant workers. Managing it all has been a cadre of super-competent professionals and technicians, while the middle and skilled working classes of past decades have largely been replaced by computers. Among the few job categories that have grown significantly have been food service, health care, and law enforcement.

Home, store, and office construction have been financed not only through foreign capital, but also through huge bank loans capitalized by deposits from businesses which utilize overnight “cash management” accounts, by individual and institutional retirement savings, and by often-substantial federal, state, and local government cash reserves. The building booms pump money into the economy through the construction industry, and the accompanying price inflation results in capital gains that yield personal income and tax revenues. All of it is dependent on automobile transportation and increasingly-expensive gasoline. Not surprisingly, the oil industry, led by giants such as Rockefeller-dominated Exxon-Mobil, has been fabulously profitable.

But this spending—it really shouldn't be called “investment”—does not lead to permanent prosperity. The cash flow stops when bank lending becomes over-extended and foreign capital dries up. In a downturn like today's, price deflation of houses and stock markets destroys wealth that existed only on paper, eliminates income from capital gains, causes retail stores to shut down, erodes tax revenues, leaves office space empty, and strikes the construction industry and its spin-offs with loss of jobs. Unemployment in other sectors follows.

Most economists cling to the myth that what we have today is really free-market economics and fail to recognize the tremendous sea changes that have made the U.S. economy dysfunctional to its roots. This means that none of the standard solutions, which are aimed merely at re-inflating the bubbles, can solve the problem.

The stalemate is exacerbated by the fact that the era of worldwide U.S. dollar hegemony that has been in place since the 1970s has run head-on into the growing strength of a united Europe, a resurgent Russia, and the Asian economic powerhouses of China and India. These nations have caught onto the game the American banks have been playing. Removal of the gold peg by the U.S. in 1971 was the start of almost 40 years of monetary warfare against the rest of the world, which is finally saying “enough.” Unfortunately, with the U.S. consumer growing poorer by the day, fewer goods can be imported from other nations which suffer as well as their export-oriented manufacturing economies decline.

Let me also observe, with respect to the tender concern which economists have that the credit markets get up and running again, doesn't this also illustrate the human tendency to “kiss the whip that scourges”? For the financial system holds everyone hostage, including citizens, politicians, and economists. An analogy might be the “Stockholm Syndrome,” where, as described by Yahoo.com:

“Captives begin to identify with their captors initially as a defensive mechanism, out of fear of violence. Small acts of kindness by the captor are magnified, since finding perspective in a hostage situation is by definition impossible. Rescue attempts are also seen as a threat, since it's likely the captive would be injured during such attempts.”

The U.S. financial industry, which is the source of the disease, still is officially regarded by the federal government as “critical infrastructure”—i.e., sacrosanct—where anything that would threaten its dominance is seen as tantamount to terrorism or treason.

Cancer

The internationally-based Empire of Usury we have been watching collapse is a qualitatively different phenomenon from earlier phases of American history. It has little to do with any of the concepts we are so familiar with such as “democracy,” “business cycles,” or even “capitalism.”

In standard economic theory, capital is one of three necessary ingredients—along with land and labor—in the process of production. Utilization of each has a cost which is calculated in a myriad of ways. The technical term for this cost is “rent.”

The appropriate type of rent to be charged for the use of capital has been controversial down through the ages. Interest and dividends are two such types. What distinguishes today's conditions is that control of capital is monopolistic, excessive, and entirely under the control of a parasitic sector, the financial industry.

An apt concept might be one drawn from medicine, since what we are seeing appears to be a rapidly metastasizing case of possibly terminal cancer. The host of this cancer is the economy of the U.S., and the cancer is deadly. The prescriptions of people like Stiglitz and Krugman, and even those now being presented President Barack Obama, are like offering a pair of crutches to a cancer patient so ill he can no longer even stand up.

The Empire of Usury is worldwide in reach and has a long pedigree. It goes back to ancient Sumeria, when debtors first began to be sold into slavery. Excessive debt ruined many of the Greek city-states and helped wreck the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, usury was viewed as such an evil practice that the Catholic Church outlawed it.

The current phase of the Empire dates to the creation of the Bank of England, which was a privately-owned banking institution that made its money by lending to the British government so it could fight its imperialistic wars. The Bank of England was cloned on American soil when the Federal Reserve System was created by Congress in 1913. The bankers had previously tried take control of the U.S. through the First and Second Banks of the United States but had been defeated by democratic forces led initially by President Thomas Jefferson (pres. 1801-09) and later Presidents Andrew Jackson (1829-37) and Martin Van Buren (1837-41).

Since the founding of the nation, there has been a struggle within the U.S. between pro-and anti-bank forces. Van Buren in his famous Inquiry into the Origin and Course of Political Parties in the United States (publ. 1867) traces the two-party system to this antagonism.

After a dramatic see-saw battle lasting two centuries, the banks finally saw complete triumph in the 1970s when the philosophy of monetarism took over and assured that a chronic insufficiency of real money in the economy would be answered by an exponentially growing amount of bank-generated debt. The flood of petrodollars overseas was paradoxically mirrored in reverse by a growing shortage of consumer purchasing power at home.

Monetarism was not directed solely by figures within the U.S. Rather it was part of a worldwide financier conspiracy. The “Reagan Revolution” which facilitated it was matched by “Thatcherism” in the U.K. and similar pro-bank regimes around the world. This included Australia and New Zealand, whose post-Great Depression prosperity was ultimately ruined by the new bank-centered financial policies.

Since American economists have failed so egregiously, we are forced to turn elsewhere for explanations. The triumph of usury—i.e., cancer—was ably described by New Zealand author Les Hunter in his 2002 book, Courage to Change: A Case for Monetary Reform .

“It was the artificial scarcity of money imposed by the application of monetarist policies that caused the usurious system to mutate from the industrial and allowed the collection of usury in amounts greater than that forthcoming as industrial economic rent. What has come to be practiced is a corruption of the investment practices that, in the past, and particularly in the industrial systems, had driven civilization forward.

“As investment proceeds within a usurious system, debt securities are accumulated and valued by the holders as income-earning assets. Of course, unlike the industrial assets such as the powered machine, a debt security produces nothing that is real.

“However, monetary income received as interest from compounding debt does give claim on current output—wealth at the point of sale—as does any form of economic rent once it has been collected in a monetized economy. Within usurious society, the rich are made richer and the poor, poorer, for no justifiable reason.”

How did this come about? Hunter writes in terms similar to those I used previously:

In the late 1960s, an aberrant socio-economic phase emerged: the usurious state, in which the control over money, rather than the ownership of machinery, is the most important lever of economic and social power. Investment in debt, and the speculative buying and selling of paper assets, are the most significant means of accumulating personal wealth.

Hunter provides the following list of characteristics of usurious systems, features that are agonizingly familiar:

- “Crushing debt;

- “A widening gap between rich and poor;

- “Share markets subject to collapse;

- “Currency meltdowns;

- “Mounting social distress;

- “A pervading belief that the free market should be allowed free reign;

- “Banks driven by profit but holding tremendous power through their ability to create and extinguish the national currency, that is, money.”

Hunter's analysis is light-years ahead of U.S. economists, who, even when playing the role of an “official” opposition, really only enable the international financial elite to continue their dominance unabated. Of course industrial society is at the mercy of this financial tyranny, because huge quantities of money are needed for a modern economy to function. Hunter continues:

“The accumulation of usurious debt—money-lenders' assets—became possible because those in business have an absolute requirement for access to sufficient working funds to pay costs. (The payment of costs is the main means of generating the national income; investment makes up the difference.)

“The money needed as working funds is defined as M1, which is the sum of base-metal coin, notes, and cheque money. It is this money that is accepted as the national currency. In many nations, applying monetarist policy has given business's working funds—as the ancillary factor of production—sufficient scarcity value that significant amounts of usury, as the relevant form of economic rent, can be, and are being, collected.”

This system is not free enterprise, and it is not capitalism. It is the cancer that is destroying the world.

Revolution

The bankers' takeover of the world economy that gained a complete triumph in the 1970s cannot be undone by President Barack Obama's economic stimulus program or any other progressive nostrum. Even the goal of creating millions of new jobs, should it succeed, is not likely to compensate in the long run for the enormous amount of debt the productive economy is carrying. But then again, Obama does not intend to overthrow the Empire of Usury. After all, a main source of campaign funds for the Democrats in 2008 was Wall Street bankers and financiers.

The amount of debt the economy is carrying is staggering. If we count individual, household, business, and government debt, that figure now exceeds $40 trillion, including the recent bailouts. What the General Accounting Office calls “unfunded liabilities” of the federal government, due to future costs of entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare, adds another $60 trillion. These estimates don't include outstanding debt for derivatives, most of it bank-leveraged, which, according to the Bank for International Settlements, may amount to $1.28 quadrillion worldwide.

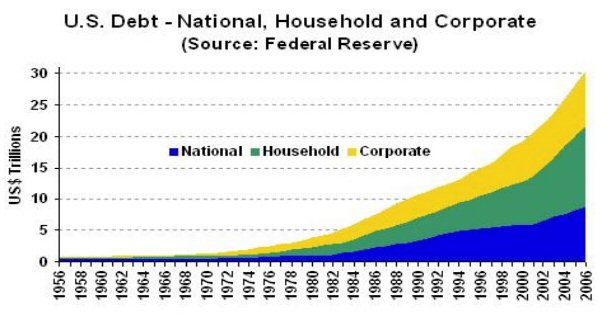

Growth in debt through 2006—understated, compared to figures derived by independent analysts—is shown by the following chart based on Federal Reserve figures. Note that virtually all of the debt has been incurred since removal of the gold peg and that its growth is exponential.

The commentators who write for newspapers like the Washington Post or give advice to the Federal Reserve have come up with solutions like slashing Social Security and Medicare benefits, a prescription President Obama will likely follow, or selling more U.S. assets to creditor nations like China. But they are proposing solutions in the interest of the financiers, not the nation.

They refuse to propose the obvious, which is that the debt must be written off as soon as possible and the monetary system changed to prevent further debt from being accumulated. Nationalization of the banks is not the answer; it still would be a debt-based system where the banks would rule from within the government rather than outside.

Bailouts financed by the government must be repaid with interest by the taxpayers. But the taxpayers are already overburdened by debt. Because the bankers are so untrustworthy and motivated by self-interest, they must be removed from power. This requires a political revolution that may already have begun.

The attack on the bankers' power must be broad, persistent, and far-reaching. Today they control the political process in the U.S. and around the world. Their power is guarded by the laws and regulations of the Western nations. They control international agencies such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization. They also influence the Western military and intelligence machines, with NATO now being sworn to protect Western “neoliberalism,” which means the bankers' Empire.

The one U.S. political figure who has called for revolution is Dr. Ron Paul, Republican candidate for the 2008 presidential nomination and author of legislation to abolish the Federal Reserve System. But Dr. Paul still favors a largely unregulated bank-based system, though one where inflation is controlled through a metallic-backed currency. But there has never been enough gold and silver in existence to provide backing for the massive liquidity needs of an industrial economy.

In the past few weeks Democratic Congressman Dennis Kucinich—also a former candidate for his party's presidential nomination—has spoken on the House floor in favor of placing the Federal Reserve under the Treasury Department. Kucinich also favors the American Monetary Act proposed by the American Monetary Institute. ( www.monetary.org )

The American Monetary Act became part of Kucinich's platform during his 2008 congressional campaign after he had dropped out of the run for the presidency.

This plan would eliminate public debt for federal government expenditures by returning to a Greenback-type system of direct government purchasing like we had during and after the Civil War. Public expenditures would focus on the creation of infrastructure assets as the basis for the monetary system. The Act would eliminate fractional reserve banking by requiring the banks to borrow money they lent from the government.

These measures would address the errors made by all Western governments by which, according to Canadian professor of economics John H. Hotson, they have violated “four common sense rules regarding their fiscal and monetary policies.” Hotson was professor emeritus of economics at the University of Waterloo and executive director of the Committee on Monetary and Economic Reform (COMER), when he identified these rules in 1996 as:

“1. No sovereign government should ever, under any circumstances, give over democratic control of its money supply to bankers.

“2. No sovereign government should ever, under any circumstances, borrow any money from any private bank.

“3. No national, provincial, or local government should borrow foreign money to increase purchases abroad when there is excessive domestic unemployment.

“4. Governments, like businesses, should distinguish between ‘capital' and ‘current' expenditures, and when it is prudent to do so, finance capital improvements with money the government has created for itself.”

The violations would be corrected by the reforms contained in the American Monetary Act. This would go a long way toward returning banking to its proper role of providing working capital for the economy but would displace the banking system as the focal point of national economic and political dominance. But these reforms by themselves still would not meet the need for a direct infusion of purchasing power into the hands of individuals. Fortunately, the American Monetary Act also contains a dividend provision, a deeply meaningful concept that we will now explore.

By Richard C. Cook

http:// www.richardccook.com

Copyright 2009 by Richard C. Cook

Richard C. Cook is a former U.S. federal government analyst, whose career included service with the U.S. Civil Service Commission, the Food and Drug Administration, the Carter White House, NASA, and the U.S. Treasury Department. His articles on economics, politics, and space policy have appeared on numerous websites. His new book, We Hold These Truths: The Hope of Monetary Reform , can now be ordered for $19.95 from www.tendrilpress.com . He is also the author of Challenger Revealed: An Insider's Account of How the Reagan Administration Caused the Greatest Tragedy of the Space Age , called by one reviewer, “the most important spaceflight book of the last twenty years . ” His Challenger website is at www.richardccook.com . A new economics website at www.RealSustainableLiving.com is upcoming with partner/author Susan Boskey.

Richard C. Cook Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.