Modern Monetary Theory – Applications in the 21st Century

Economics / Economic Theory Jul 05, 2019 - 05:08 AM GMTBy: Andy_Sutton

Perhaps one of the biggest frauds perpetrated on the citizens of the world in the 20th century was Keynesianism. For those of you who are new to the discourse, Keynesianism was essentially the ramblings of a well-respected (at the time) economist named John Maynard Keynes and it dealt with deficit spending at the level of the federal government. It was a justification for something governments around the world were beginning to do anyway. The point of Keynes’ work was to give this very dangerous and ill-advised practice legitimacy. Sadly, it worked, and 85 years later, the developed nations of the world are mired in debt the likes of which the world has never before seen and may well never see again.

Perhaps one of the biggest frauds perpetrated on the citizens of the world in the 20th century was Keynesianism. For those of you who are new to the discourse, Keynesianism was essentially the ramblings of a well-respected (at the time) economist named John Maynard Keynes and it dealt with deficit spending at the level of the federal government. It was a justification for something governments around the world were beginning to do anyway. The point of Keynes’ work was to give this very dangerous and ill-advised practice legitimacy. Sadly, it worked, and 85 years later, the developed nations of the world are mired in debt the likes of which the world has never before seen and may well never see again.

Before we get to the true purpose of this paper: an analysis of MMT, we must lay some foundational work. Please bear with us. If you have been an active reader of our previous articles and research, feel free to proceed directly to the portion where MMT is addressed.

Interestingly enough, the topic of this paper; (another consequence of treating economics as a debating society instead of a science) the foundations of modern monetary theory (hereafter MMT) actually originated long before Keynes wrote his seminal work in 1936. MMT as it is being rehashed today was actually first described by a German economist name Georg Friedrich Knapp in 1905. Originally coined ‘chartalism’ by Knapp, this perversion of economics was pushed in Knapp’s 1905 ‘State Theory of Money’. The term comes from the Latin root charta, which means ‘token’ or ‘ticket’.

Knapp believed that money was not originally created to solve the problem of coincidence of wants which limited direct exchange economies. Rather, Knapp felt money was created by the state in order to direct and control economic activities. We will not argue for even a second that various governments haven’t done exactly that, however, his opinion on the origination of money is patently false. Specifically, Knapp believed that legal tender laws were the instrument used to take control of economic activities. The truth of this statement notwithstanding, however, is a discussion for another essay.

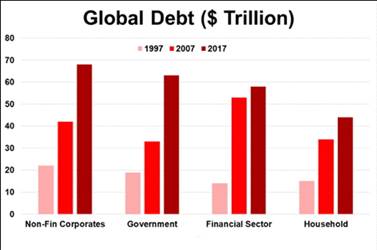

Data Sources: IMF, BIS, Haver Analytics

Nearly all US university economics programs are centered around Keynesianism, although classical and monetarist approaches are given some seat time. The Austrian capital by economic forbearance model is almost never mentioned even though, if followed, it would lead to positive economic outcomes both at the macro and micro levels in both the short and long term (Rothbard 793). The end result is there is precious little economic understanding beyond the myopic and slanted (actually, bought and paid for) views of Keynes’ faulty hypothesis outline in “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money”, which was published in 1936 during a critical time in history, particularly from an economic standpoint. Keynes justified the use of deficit spending as a weapon against economic recession, and in the 1936 timeframe, economic depression. However, even Keynes wasn’t foolish enough to opine that deficit spending should be become a way of life. Rather, he pointed to such activity as a short-term policy tool. Even the better Economics texts leave this last part out of the analysis.

Which bring us to the present day and the bind these same developed nations once again find themselves in. Runaway deficit spending has led to a $22+ trillion dollar national debt in the US, but that isn’t even half the story (usdebtclock.org, Treasury Department). The USGovernment loves to use its own accounting rules – which are changed anytime it is politically expedient. Forgotten is GAAP or generally accepted accounting principles. If a company fails to use GAAP, fines, sanctions, and possibly jail time await those who transgressed. However, since the USGovernment has a hard time prosecuting practices that have become institutionalized, you don’t hear what the REAL net present value of the national debt is.

Laurence Kotlikoff, a friend of the authors, has estimated, using GAAP, the net present value of the national debt at somewhere between $224 and $242 trillion dollars and is tabulated by a growing number of concerned Economists (Gunn). The total US money supply (obfuscated by the not-so-USFed since March 2006) but easily reproduceable is currently around $18 trillion. (Kotlikoff, Gunn)

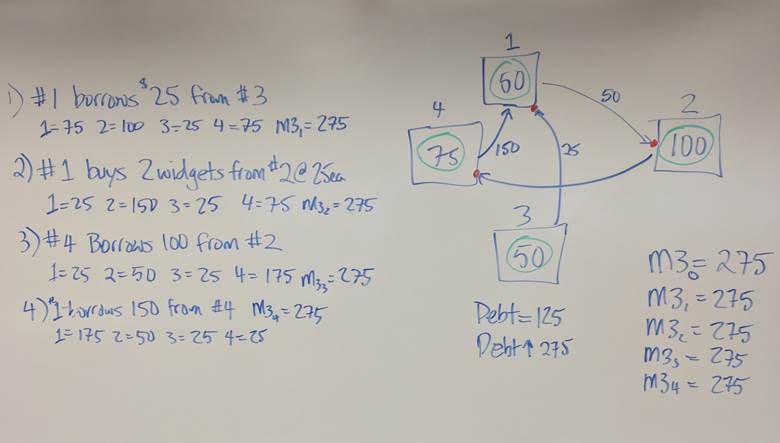

The money supply though, is transaction-based, not possessive. In other words, we don’t need to create $22+ trillion new dollars to pay off the national debt. We can demonstrate this with a simple illustration:

In the above example, we start with a money supply of $275, distributed unevenly among 4 economic actors. We conduct 4 transactions, 3 of which involve borrowing. The other is a purchase. At the end of the simulation, we have accumulated $275 of debt and our money supply is STILL the same $275 it was at the beginning of the simulation. We can draw 2 conclusions from this brief exercise. 1) Debt creation is not inflationary so long as we don’t allow fractional reserve banking. For example, if we add a bank to our mix and the bank is allowed to loan out 90% of all deposits, we will witness monetary inflation. Let’s say Actor #1 in our example puts his initial $50 on deposit with a bank. If the bank hangs on to the entire $50, then the money supply is stable.

If, however, the bank then lends $45 (90%) of the $50 deposit, then we’ve increased the money supply by $45 because the bank still has the responsibility of returning the $50 deposit to actor #1 and it’s already loaned $45 to another actor. 2) We can also draw the conclusion that we can run up debt equal to the original money supply without creating a single marginal currency unit. Applying the above exercise to the US national debt, it is absolutely possible to run up a $22 trillion debt with a money supply that is significantly lower. Again, money is transactional as well as being a unit of account.

However, the level of debt has become so massive that it is very clear that it will never be paid off and the Treasury issues more and more bonds every week to finance this fiscal malfeasance. Despite this, the USGovernment continues to enjoy sterling credit ratings from corrupt agencies like Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings. Why do we say corrupt? These agencies perpetrated a massive fraud when assigning ratings to tranches of subprime mortgages leading up to the 2007-08 meltdown of the mortgage backed securities market. Nobody went to jail. No meaningful action was taken. Eurozone nations have been dinged by these agencies for having debt in excess of 106% of GDP. The US is beyond that now – and if you use the GAAP numbers (if an honest analysis is to be performed then the same standards that apply to businesses must be used), it is several orders of magnitude beyond the levels of the Eurozone, but no ratings ding occurs, a brief downgrade that began on August 6th, 2011 due to the unresolved ‘debt ceiling’ issue notwithstanding. Every Treasury debt device issued gets a AAA, (or equivalent based on the firms’ rating nomenclature) no questions asked. Why? The premise of MMT will actually cover this quite nicely.

According to the IMF, global debt (non-GAAP) terms reached $152 trillion in 2015. Current debt levels place the debt to GDP ratio at 225%. (Fiscal Monitor) The IMF’s own aforementioned publication points to the obvious negative feedback loop where deleveraging is concerned. “Put simply, it is very difficult to deleverage because using wages and savings to pay off debt instead of using those funds for more purchases will have a deleterious effect on aggregate demand, and, eventually GDP. The drag on GDP then causes wage stagnation and high unemployment, which leads to debt accumulation since there is precious little savings outside the retirement system”.

In the current American circumstance, it is viewed much more favorably to take on debt to meet wage and income shortfalls than it would be to liquidate retirement savings to fill those gaps even though it SHOULD in fact be considered in many cases. However, in the United States, giving such advise would be considered below the standard placed on fiduciaries such as investment advisers. Why do we mention this? When MMT has been fully laid bare this will be mentioned again and it will be apparent.

Where does MMT fit in?

Government in general has a tremendous appetite for spending. Pet projects, pork barrel spending, it doesn’t matter what you call it; government loves it. There is an old saying that there is nothing as permanent as a temporary government program. Politicians love the adoration of their constituents and they gain that adoration increasingly by throwing pork to the masses. That is the state of the world today. Responsibility is nearly absent. Everyone is looking for someone else to fix their problems.

When we talk about financial and fiscal matters, people look to government. The IMF started 2019 with a serious campaign regarding the ‘Universal Basic Income’ or UBI as they call it. Notice all of these terms have acronyms. Governments of the world have used minimum wage for decades now to create’ a UBI, but it never works. Why? It’s not because the government isn’t raising the minimum wage enough – it is because there wouldn’t need to be a minimum wage at all if we were still using sound money.

Unfortunately, using sound money principles puts a serious damper on all this profligate government spending and we just can’t have that. Look at GDP and then pull out JUST the Federal deficit and see what GDP growth looks like. We’ll tell you. It’s gone. There’s negative growth. A recession at minimum. Best case. Another hurdle for the UBI is that it is to be provided to all (definite socialism) regardless of whether these people work or not. That is how it’s being packaged in the US. It’s a redistribution of wealth with the government acting as the conduit. If that isn’t socialism, then what is? Words mean things and instead of saying ‘welfare’, which now carries certain negative connotations along with it, they create a new moniker – UBI.

MMT asserts that any government can create its own money and uses the US as an example. This is a false assumption in the case of the United States. Many will ask why we chose to make a big deal out of the ownership of the Federal Reserve? There are two reasons. First, there is so much misinformation regarding this rather secretive bank. Secondly, since the US Government cannot issue its own money, one of the pillars of MMT is immediately called into question.

The Federal Reserve, on its website, mentions its stockholders – all chartered US Banks - which are private businesses, not public entities. These shareholders receive a dividend payment based on the number of shares they hold. This happens exactly as it would with any other PRIVATE company that pays dividends. This is not a theory or an opinion. This is how it is. There are no opinions on this matter as it is a fact. This is an admitted and very public fact.

It is extremely dishonest, from an intellectual standpoint, to raise opinions then present them as facts. This is one of the reasons why the mainstream media has sought to turn everything into an argument – even when pertaining to issues where facts are clearly present. Everything is a debating society; open to interpretation. This is no accident. We would not be surprised if 2+2=4 doesn’t come under some sort of attack. That is how twisted the situation regarding information has become. When we apply this to economics, we take something that is rather easy to understand and kill it first with terms, then with nonsense statements such as “You can’t count the amount of money that Medicare owes to the FDA (or some other government agency) – because we owe it to ourselves”. This statement totally dismisses the notion that there must be production and saving of excess to clear the debt REGARDLESS of the creditor.

Therefore, the basic premise for MMT is fraudulent and inaccurate. What difference does it make though? Does it really matter that the Federal Reserve is private and not part of government? What if the Treasury Department issued all this money instead? The point of fact is simple. There is interest inured to the Federal Reserve for every dollar in the system. This interest is paid primarily by the people of the United States with units of labor. Some will argue that all of the not-so-USFed’s profits are returned to the Treasury. This cannot be true since the ‘Fed’ claims to pay its member/shareholder banks a 6% cumulative dividend, shown below:

"After all necessary expenses of a Federal reserve bank have been paid or provided for, the stockholders shall be entitled to receive an annual dividend of six per centum on the paid-in capital stock, which dividend shall be cumulative. After the aforesaid dividend claims have been fully met, the net earnings shall be paid to the United States as a franchise tax except that the whole of such net earnings, including those for the year ending December thirty-first, nineteen hundred and eighteen, shall be paid into a surplus fund until it shall amount to one hundred per centum or the subscribed capital stock of such bank, and that thereafter ten per centum of such net earnings shall be paid into the surplus.”(federalreserve.gov)

Summarizing the above, Federal Reserve stockholders get their 6% before the Treasury sees anything. If there aren’t enough earnings on the assets of the Federal Reserve, the dividend accumulates until there are enough earnings to pay accrued dividends. Only after this obligation is met does the Treasury receive its cut. This clearly makes the Federal Reserve a for-profit, private institution.

Closing the circle, the fact that the Federal Reserve keeps money aside from its activities to pay its shareholders (instead of returning all proceeds to the Treasury) means Americans are paying for the services the Federal Reserve offers, including, but not limited to, the use of its currency even though the Treasury prints it.

If the Treasury issued the currency (as it did prior to 1913), there would be no interest incurred. As the system exists now, the Treasury – through the fiscal malfeasance of the Federal government – owes massive amounts of both principal and interest to various international entities merely for transgression of using the currency of those institutions. In Article 1, Section 8, the US Constitution has a far better answer. Had the government actually stuck to the Constitution we wouldn’t have private banks owning ever increasing amounts of our economic activity. Sadly, most people don’t see this as a problem.

How is MMT really any different in that regard? It’s not. Many aspects of MMT have, in fact, been in practice in the United States and other First World (OECD/G20, et. al.) for decades. Let’s take a look at the tenets one by one.

A government, such as the United States, that is able to print its own money:

1) Cannot default on debt denominated in its own currency;

2) Can purchase scarce goods without collecting taxes or issuing debt preceding such purchases;

3) Is limited in purchases and monetary creation by inflation, which accelerates once all scarce resources are in play at full employment;

4) Can control inflation by taxation and bond issuance, which remove excess money from the system, although this hinges on the political climate and may or may not happen efficiently;

5) Does not need to compete with the private sector for scarce savings by issuing bonds.

The allegation by proponents of MMT state that government should not be a priori when it comes to spending and taxation. It should, instead of taxing and issuing bonds to gain revenue with which to spend, simply create as much money as it needs, then deal with the resulting inflation with taxation and bond issuance.

Let’s now dissect these pillars one at a time:

1) Cannot default on debt denominated in its own currency. This is no change from the current model in that the not-so-USFed is always willing and able to print as much money as is needed to monetize debt and provide liquidity. This is one of the biggest underpinnings of the foolish notion that the US can never go broke. Never addressed, however, is the notion of value of the USDollar in either the current arrangement or MMT. Notice not a single mention of the value of the currency unit was made in the 5 major underpinnings of MMT. Secondly, this premise is foolish because why would any country denominate its debt in anything other than its own currency. The one possible grey area is the European Union. Greek debt, for example, is denominated in Euros rather than Greece’s former national currency, the Drachma.

Why any country would agree to giving up sovereignty by ceding control of its currency to a third-party central bank is beyond the authors, but sadly, we only need to go as far as the nearest ATM to find the biggest example of exactly that. When Congress ratified the unconstitutional ‘Federal Reserve Act’ on December 23rd, 1913, it violated Article 1, Section 9 of the US Constitution. So, we’re supposing we should really be calling it ‘pseudo modern monetary theory’ since the entire premise is a complete washout.

Why is it an essential necessity to belabor this point, however? The fact that the US is using a third party, private central bank is the crux of the entire matter. The two ‘mandates’ that the not-so-USFed was given were price stability and maximum employment. Sadly, it has an extremely poor record on both counts. The USDollar has lost around 96% of its purchasing power since 1913. The performance review on the price stability front receives an F. The economic roller coaster the country has been on, resulting in many periods of double-digit unemployment gives the ‘fed’ an F where it comes to full employment also.

2) Government can purchase scarce goods without collecting taxes or issuing debt. This tenet of MMT is basically the reverse of how things are done now. Let’s assume for the purposes of explanation and simplicity that the United States in fact does create its own money. We’ll cut out the not-so-USFed for now.

MMT dictates that if the government needs funds to undertake a project that it can just create the money for the project, spend the money into the system, then deal with inflation later through the issuance of bonds and taxation. At the present time, the government issues bonds and taxes in order to get the funds to conduct its activities. What is the difference? There are currently devices in place to pull money from the system in the event the bankers declare it to be necessary. It’s been dubbed quantitative tightening. The fed sells assets that it has accumulated in the past, during the various economic and banking crises it has helped create. This pulls money from the system. The fed also has the ability to tweak reserve requirements for banks, which will result in less monetary creation when deposits into the banks are made by individuals and businesses.

In the MMT model, the money would be printed and fired into the system first, then when the monetary excess started driving up prices, the money would be removed from the system by taxes and bond issuance.

It is this last point that interests us the most: Taxation. In order to keep price levels steady, there has to be enough money in the system to lubricate financial transactions, but not so much that the purchase of goods turns into a bidding war. One of the fed’s mandates was price stability (or, put another way, the purchasing power of the currency units). The fed has (intentionally in our opinion) done an absolutely terrible job with this mandate. The money supply is all over the place. Money zips between the various asset pools with the government running interference in terms of trying to ‘direct’ the excess currency. An example of this would be the ease of getting a mortgage in the 2002-2007 time window. This channeled trillions into the housing bubble. When the bubble burst, the homeowners went to the wall and many lived in tents – some to this day – while every bank that needed a bailout got one. Even if the fed were well-intended, which we don’t believe is even a little true, it would be difficult to levy taxes and issue bonds at the right time. It would be hard to hit the correct tax rate. The complexity of the financial and monetary system almost ensures that. Tax rates would be all over the place; the only indicator people would have of their upcoming tax bill would be how much prices are moving – IF removing money from the system was the only goal.

Given the proclivity of government to protect corporations (fascism true to definition), what can we make of the taxation portion of MMT? Nothing good, if history is any indicator. Given that money will be removed at the level of the system where prices are increased (ie: demand is monetized), the punishment for consumers will be marked and profound. Smaller business will be hit hard as well. The not-so-USFed has done an absolutely terrible job of keeping prices stable and now we are supposed to believe that suddenly, if the process is flipped around, that they’ll now be able to handle price inflation? As we posited above, it’s not going to happen. We believe there are much better odds of the taxation portion of the MMT framework to be used in a punitive or distributive manner, perhaps under the auspices of the universal basic income concept that is being pushed so hard by the IMF, World Bank, and Bank for International Settlements among others the past few months.

3) MMT also asserts that inflation is not seen unless and until all the factors of production are at total utilization during periods of full employment. Given that America has had many, many periods of simultaneous significant unemployment AND inflation, this assertion is rather comedic. The stagflation of the late 70s and early 80s comes to mind immediately. Again, the devil is in the details. Proponents of MMT view inflation as a price event, rather than a monetary one. Once again, they would be patently mistaken. This faulty assumption made by MMT proponents is obvious in the wording. They are positing that prices cannot rise unless and until all factors of production are in use during full employment. To put this assertion in correct terms, MMT advocates are saying that the money supply cannot increase unless and until all the factors of production are in use during full employment. But here’s the rub – the monetary event, according to MMT, occurs BEFORE full employment and full utilization are ever reached. This proves MMT is a fraudulent concept on its face.

Given that the whole point of MMT is to print first then ask questions, it is obvious they’re looking at inflation as a price event, which means the entire theory is non-salvageable as a viable hypothesis. Let’s play it out through an example:

It has been estimated by several groups that the cost of the New Green Deal in particular would be north of $90 trillion. Not all of this money will be needed at once, nor does $90 trillion need to be printed to do $90 trillion worth of infrastructure upgrades – see our aforementioned exercise. However, since the government is broke, it’ll need to have the not-so-USFed print up a pretty large batch of new money to get the process rolling. Even without full employment, it is possible (and it’s happened) to see inflation. Basically, once the new money hits the streets and contractors start bidding on scarce materials to do the various projects involved, prices will begin to rise in some areas. Put a different way, the creation of new money is essentially monetizing demand.

Following our example, and applying the tenets of MMT, as soon as prices begin to rise, the government should begin to pull money out of the system to get inflation under control – here they come close to getting it right. So now that prices are rising, the government will either tax or issue debt, which will, in theory, pull the money that is causing prices to rise out of the system and cause prices to revert back to original levels. The obvious point of MMT is for the government to buy every manner of pork on its ‘wishlist’ by putting money into the system, then yanking the money out of the system as soon as prices start to increase. Said another way, under the tenets of MMT, the government controls the factors of production. Such a move would close the circle and create the socialist dystopia we hear so often squawked about by socialists in the government and elsewhere.

In order for this poorly conceived stunt to be successful, the government must become a master of partial equilibrium analysis. Let’s use an example of repairing bridges along the Interstate system. Let’s use concrete as an example. The project will require a massive amount of concrete. So the government creates the money and starts subbing work out to concrete contractors. Remember, we’re already talking about full utilization of the factors of production under full employment, which MMT purports to cause and maintain. Give the government’s current assertions, we are already working in a situation of maximum employment and low inflation – in terms of prices (Wigle 2).

All price controls currently in effect notwithstanding, the entry of currency units at the margin will begin to push prices up because we’re already at full utilization according to the government. When the government’s subcontractors start bidding for the massive quantities of concrete required for Interstate bridge work, the price will increase. The government then must immediately withdraw money from the system to get concrete prices back down – think partial equilibrium again. There is increased demand for concrete and this demand is monetized by the new money created by the government. This process will be repeated over and over again until all the concrete for the project is obtained.

However, what is not considered is how withdrawing money from the economy in order to bring concrete prices back to pre-inflation levels will affect the rest of the economy – general equilibrium. Concrete is a single good. How does the government tax or issue debt to pull money JUST from the actors that would bid on concrete, thereby keeping prices down? Furthermore, will pulling money away from those actors guarantee that concrete prices will drop? Remember, we are repairing the interstate system. These economic agents (construction contractors) will continue to need concrete to finish the job. Will we enter an endless cycle of directed monetary infusions, purchase of goods, then targeted removal of money to essentially demonetize the demand for concrete? Will this process be Pareto efficient? Will it make one or more actors better off without making one or more actors worse off? (Kotlikoff, Auerbach 76)

Again, remember, we’re talking about one item here – concrete. We have already experienced MMT in America (and continue to) from a general equilibrium perspective. We have seen inflation ‘directed’ for lack of a better term into asset bubbles rather than into consumer prices. The former type of ‘inflation’ is considered to be favorable whereas the latter is generally considered to be unfavorable. This exposes the folly of examining the concept of inflation from a price perspective. The only real difference between the MMT outlined above and the current implementation of MMT (or its illegitimate cousin) is that the process is reversed. Currently, the government issues debt – because it CANNOT print its own money – then goes out and imitates spending activities. Normally, this would cause a general rise in price levels. However, the government has tried to direct or channel much of the inflation we’ve been seeing into things like the housing market, stocks, debt itself, and other areas where an increase in prices is seen as a good thing.

There really isn’t a good way to approach such an undertaking from a partial equilibrium standpoint, although, to prosecute MMT properly, that’s exactly what one must do. Once we realize the only way to run spending/inflation/taxation program without hiring an army of economists to track every product – or at least every product category, is to approach it from a general equilibrium approach. There must be enough money in the economy to facilitate all transactions, but not so much that there can be an upward push on prices. Now that we’ve made this conclusion, how will we measure inflation? MMT advocates watching prices and see what happens when money is injected into the economy. This is actually fairly close to what SHOULD be going on now. Today’s policymakers know this, but, for the public’s benefit, they only focus on the price side of the inflation situation. They ignore the monetary side, except behind closed doors.

4) Excess money can be removed from the system via taxation and bond issuance. This is beginning to get repetitive; MMT was never a good concept as a way to run an economy. Knapp knew this because his own beliefs were that the state used money as a weapon against the people. This was the premise upon which MMT was constructed. Oddly, even under the auspices of MMT, the state can still use money as a weapon against various groups of economic actors. Think taxation. Taxes/fees/levies/surcharges can be created, and are already being used, to hamper particular groups of economic actors. Most of these situations in the United States are directed at the ever-shrinking ‘middle class’. These are the people who make too much money to be on the government transfer payout list (aka: public dole) but make too little to be able to deny the impact of these seemingly ever-increasing fees. The fees hurt and the state knows it yet continues to do it anyway. If that isn’t using money as a weapon, then there is no better example. This is chartalism at its finest – according to Knapp’s work - and we would be hard-pressed to disagree.

There are a few questions that need to be asked here, namely: “How much excess is too much excess?” How do we track price levels? How do we decide when to pull money out? How do we leave enough money in the system to allow for economic growth? The problem has always been that growth is measured in prices paid using a currency that is continuously losing its value. Our dire fiscal situation is screaming for a return to sound money principles, but instead of admitting this is the case, the monetary mafia are doubling down on their own broken system and paying us all lip service in terms of price stability, which we can tell you will not happen. Given this ‘power’, the USGovt, in conjunction with the fed will print money for all of its pet programs, UBI, etc. then tax the daylights out of the economic producers once price levels start going up.

5) The government won’t have to compete with the business sector for scarce savings. Currently, the government issues bonds to pull savings from the economic ‘sidelines’ and get them into the game. Private businesses are also vying for that savings in many cases and they may issue bonds as well. Since MMT presumes the government is not going to have to compete with private business for savings, is a prohibition on corporate bonds going to take place? Or is the government going to buy those bonds to push businesses forward?

What does this mean for the personal or business saver? What becomes of the ones who create capital in an economy through foregoing of consumption and the storing away of the excess? Can a government, running under the tenets of MMT, allow private sector savings at the firm and individual levels? Those actors may decide to make their capital available to other economic actors and those actors will deploy these funds and put additional pressure on prices. How does a government control this? The answer is elimination of private sector savings through taxation as a primary measure. Converting private savings to public savings through bond issuance would be a secondary approach, but there is no guarantee that holders of private capital pools would be inclined to lend money to an entity (assuming that purchasing bonds would be voluntary) that is persecuting those who save, thus we believe that taxation would be a more reliable way to execute the conversion (theft) of private capital.

In conclusion, when one considers the 5 pillars of MMT then looks at the analysis, it is hard to conclude anything other than MMT is being weaponized as a form of policy position to essentially hijack the USEconomy and probably other major economies along with it in favor of a more socialistic approach. The key piece in all this is that a good portion of the MMT playbook is already in use. The IMF and its various mouthpieces have been pushing the Universal Basic Income for quite some time now and the cries for UBI have been increasing rapidly as we navigate 2019. Several US cities are already drawing up plans for a UBI. Let’s be honest here – the UBI is nothing more than yet another socialist scheme that sounds great to people who for whatever reason cannot or are not interested in working. It’s the welfare state, ‘Great Society’ of the 1960s with an added punch. This presents yet another problem for government. If the state is going to monetize additional pools of demand through money handouts, then how it is going to remove said money when the inevitable general price level increase comes? Our opinion is that the taxation will be aimed squarely at the shrinking middle class – both in the US – and abroad. However, persecuting economic producers in the long run has its drawbacks. Disincentivization comes to mind as the biggest problem.

Before we conclude, we need to re-visit our earlier assertion that under an MMT or even a pseudo-MMT system it behooves one to consider draining savings as opposed to taking on debt. The fact that our global society takes on debt without the least bit of consideration notwithstanding, there are major reasons why we must look at this in greater detail.

The first is that, very simply put, the returns one might hope to reasonably gain by investing money are far less than the cost of the debt (the interest rate paid on the debt). Few people recognize this and it is glossed over in most areas of consumer financial education, but there are several costs associated with borrowing money. The first is the interest paid as mentioned above. The second is the opportunity cost – what else might the economic actor have done with the interest that is now being paid to a lender? Let’s assume we can earn what is considered to be the ‘long-term’ rate of return for the broad sharemarket – generally accepted to be in the 7-8% range, varying by data source. If it costs 9.9% to borrow the money for a particular expenditure, the actor is better off draining savings. In the case where there are penalties for doing such as is the case with qualified retirement plans, then that must be calculated in as well. Given that our society puts packs of gum on the credit card at 19.9% (this is rather common) without even thinking, the issues of drawing from savings is a valid one. The opposite side of this particular point is the purely pathetic amount of savings the world has as a whole. The draw-down of savings wouldn’t last very long.

The second point is that in an MMT system, the government prints money until prices begin rising, then removes the money that is ostensibly causing the price inflation from the system with taxes and/or issuance of debt. Let’s use our typical situation where an actor puts a high definition television on the credit card at 19.9%. Now the actor is encumbered monthly until the debt is satisfied. Let’s say this transaction occurs in the monetary creation phase of MMT. All is well. There’s plenty of money to be borrowed. However, let’s say that once our actor starts making payments that price inflation begins to accelerate and the government begins withdrawing money from the system via taxes (very likely on our borrower) and issuing debt. The big question that so-called champions of MMT cannot answer is this: Will there be enough money left in the system for our borrower and everyone else in that position to actually make payments on their debt? Or, will MMT cause them to default? Remember, money is transactional, not possessive, as we illustrated above, but there still needs to be enough money to lubricate the economy and enable transactions to occur – and debts to be paid down.

Assuming that there will be enough money to pay down debts is putting an awful lot of trust in the monetary ‘authorities’ to a) be able to get it right and b) actually WANT to get it right. Remember, the point of taxes and debt in MMT is to reduce prices – including, but limited to, the price of labor. Using our example from above, the goal is not only to bring down the cost of concrete, but ultimately to bring the cost of labor down. Why labor? Because a workforce with less money cannot afford to pay the higher price levels because there simply isn’t enough currency to do so. Think of a supply shift to the left.

If in fact the United States, the G20, etc. actually adopt MMT as a formalized monetary policy initiative, the first duty for individuals will be to actually read any language that is available regarding the actual implementation. The key to surviving such a switch is to understand how much and by what means money will be created under the system, understanding the various triggers that will cause the monetary authorities to reverse the process, and behaving proactively in the economic sense. The economic landscape is dangerous enough as it is for the uninformed. With governments pushing money all over the place on a scale even larger than what is already taking place, getting caught on the wrong side of the fence will be catastrophic. Right now, it isn’t such a big deal. MMT is actually being implemented gradually – as we write this. It’s incrementalism at its dubious finest. For now, terms like ‘quantitative easing’ and ‘quantitative tightening’ are being used. The MMT activities are being performed at the central bank level. MMT hasn’t hit Main Street – yet.

In our opinion, MMT will be the carrot, but the stick will end up being the same as it is now: wealth redistribution, rampant money printing, and deficit spending will once again be ‘affirmed’ by the best and brightest ‘economists’ in the world. Similarly, like 1936, the whole thing will be a complete lie and the G20+ will burn into the second stage of an already far out of control debt crisis. Therein lies the crux of the matter. People are starting to ask questions regarding the sanity of our current fiscal trajectory. MMT is nothing more than an elixir intended to calm the frayed nerves of the few economic actors still paying attention to such matters.

There is one, more frightening matter, however. Over the past 18 months, there has been much rhetoric, which claims that the central banks of the world are backed into a corner, from a policy perspective. They’ve fostered a massive debt-based economic system. To this point, they’ve done a reasonable job of keeping monetary creation to a minimum, which has allowed the developed nations of the world to run massive debts without the appearance of runaway price inflation. The cornerstones of this approach have been to keep wage growth at such a level that there is no opportunity for a wage-price spiral, and to direct transactions into favorable areas such as the various asset classes.

The common wisdom asserts that the central banks cannot raise interest rates to quench price inflation that does occur because that will kill off the global economy through unsustainable increases in the cost of borrowing. The opposite side of the coin is the fact that the global central banks have been on a coordinated program of easing for the last dozen years. The program was called ‘ZIRP’ – zero interest rates to perpetuity. The not-so-USFed did a series of token increases, but the elasticity of demand for debt amongst both the American public and corporations seems to be sufficient to endure these modest increases. One can reasonably draw the conclusion that the central banks are far from powerless at this point. It’s a very dangerous game, however. Given that no major global currency is currently backed by anything tangible, the entire global economy is a giant confidence game.

This is why we believe concepts like UBI and MMT are so important to the monetary establishment moving forward. UBI throws a significant chunk of the United States and Europe a rationalization for existing and expanded transfer payments, while MMT becomes yet another poorly conceived, yet intentional excuse for printing even more money and lighting the afterburners. Simply put, these gimmicks are just another way to buy more time under the current paradigm while shifting the basis of public discourse solidly in the direction of abject socialism and the poverty that accompanies it.

Graham Mehl is a pseudonym. He is astonishingly bright, having received an MBA with highest honors from the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania. He has also worked as a policy analyst for several hedge funds and has consulted for several central banks. Among his research interests are finding more reliable measurements of economic activity than those currently available to the investing public using econometric modeling and collaborating on the development of economic educational tools.

Andy Sutton is a research and freelance Economist. He received international honors for his work in economics at the graduate level and currently teaches high school business. Among his current research work is identifying the line in the sand where economies crumble due to extraneous debt through the use of econometric modeling. His focus is also educating young people about the science of Economics using an evidence-based approach.

Bibliography

Rothbard, Murray. “Man, Economy, and State”, The von Mises Institute Press, 1971 et al. pp. 770-992 specifically, and numerous pages as background.

Kotlikoff, Laurence J. and Auberbach, Alan J. “Macroeconomics – An Integrated Approach”, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Pp. Numerous.

Kotlikoff, Laurence J. “17 Nobel Laureates and 1200+ Economists Agree with Ben Carson re US. Fiscal Gap”, Forbes, 13-May 2015. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kotlikoff/2015/05/13/17-nobel-laureates-and-1200-economists-agree-with-ben-carson-re-u-s-fiscal-gap/?utm_campaign=JM-305&utm_medium=ED&utm_source=for#614a61734d17 Accessed 10-May-2019.

Gunn, Murray. “Global Debt: $233,000,000,000,000”, https://www.deflation.com/Articles/Global-Debt-233000000000000, 9-January-2018.

By Andy Sutton

http://www.andysutton.com

Andy Sutton is the former Chief Market Strategist for Sutton & Associates. While no longer involved in the investment community, Andy continues to perform his own research and acts as a freelance writer, publishing occasional ‘My Two Cents’ articles. Andy also maintains a blog called ‘Extemporania’ at http://www.andysutton.com/blog.

Andy Sutton Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.