Venezuela's Opposition Is Playing With Fire

Politics / Venezuela Feb 17, 2019 - 04:50 PM GMTBy: Steve_H_Hanke

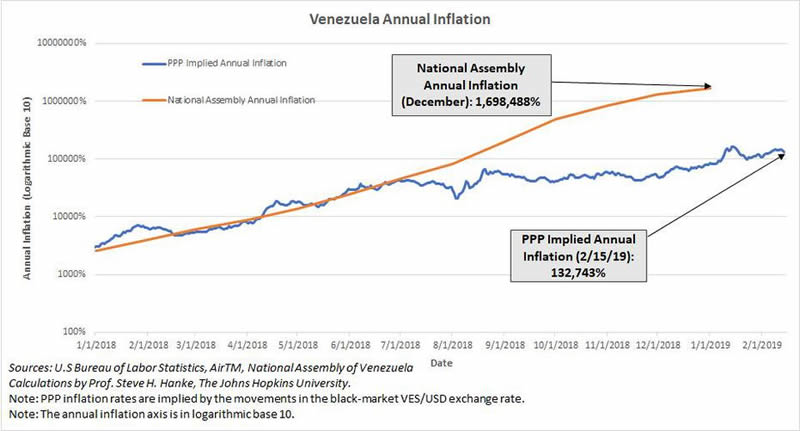

The Maduro government has put Venezuela in Satan’s record books. That hellish distinction is because Venezuela is in the grip of one of the world’s 58 episodes of hyperinflation. Hyperinflation occurs when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50%/mo. for at least 30 consecutive days. Of the 58 episodes of hyperinflation, Venezuela’s inflation rate is middling: it ranks as the 23rd most severe episode. Today, I measured Venezuela’s annual rate of inflation at 132,743%/yr. (see the chart below). This contrasts sharply with the National Assembly’s lying statistic of 1,698,488%/yr. for December 2018 and the IMF’s absurd forecast of 10,000,000%/yr. for December 2019.

The Maduro government has put Venezuela in Satan’s record books. That hellish distinction is because Venezuela is in the grip of one of the world’s 58 episodes of hyperinflation. Hyperinflation occurs when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50%/mo. for at least 30 consecutive days. Of the 58 episodes of hyperinflation, Venezuela’s inflation rate is middling: it ranks as the 23rd most severe episode. Today, I measured Venezuela’s annual rate of inflation at 132,743%/yr. (see the chart below). This contrasts sharply with the National Assembly’s lying statistic of 1,698,488%/yr. for December 2018 and the IMF’s absurd forecast of 10,000,000%/yr. for December 2019.

Prof. Steve H. Hanke

Although Venezuela falls in the middle of the pack when it comes to hyperinflation magnitudes, it is experiencing an extended hyperinflation—28 months and counting. This ranks Venezuela’s episode as the fifth longest in history.

It is clear that the number one problem facing any new government in Venezuela will be to crush hyperinflation. If a new government solves the hyperinflation problem, it will gain immediate credibility. Then, it will be able to proceed to clean up the mess created during the Chavez-Maduro years. If a new government fails to smash hyperinflation and establish stability, it will face the public’s wrath and will be short lived.

To smash hyperinflation, a new exchange-rate regime will be required. Venezuela has a self-proclaimed “President” Juan Guaidó, a man plucked from the opposition. However, it is not clear what his views, or other members of the opposition's, are on what would be Venezuela’s new exchange-rate regime.

But, there are straws in the wind. On February 2nd, The Economist reported in a “Briefing” on Venezuela that the opposition was cozying up to Ricardo Hausmann and his “National Plan: the Day After.” This plan calls for a massive amount of foreign aid and government-to-government credit, huge write-downs on Venezuela’s debt, and an opening of Venezuela’s oil sector to private oil companies. However, Hausmann is rather short on details when it comes to solving Venezuela’s number one problem: hyperinflation. All he told The Economist is that he favored a pegged exchange rate system, as opposed to a currency board. He also indicated that he didn’t wish to discuss the details of his peg plan in public because it might spawn currency speculation. So, we don’t know exactly what he has up his sleeve. But, we know enough to conclude that if the opposition embraces any one of the many variants of a pegged exchange-rate regime, it will be playing with fire, and it will fail.

Indeed, pegged exchange-rate systems are fatally flawed. They have a near-perfect record of failure. In contrast, currency boards, the system Hausmann eschews, have a perfect record of success.

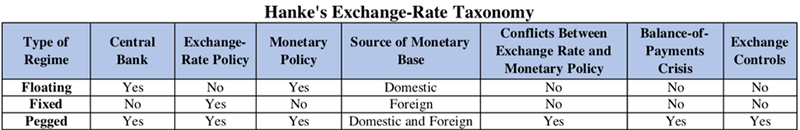

To understand why, consider that there are three distinct types of exchange-rate regimes: floating, fixed, and pegged, each with different characteristics and results (see accompanying table).

Prof. Steve H. Hanke

Although floating and fixed rates appear dissimilar, they are members of the same free-market family. Both operate without exchange controls and are free-market mechanisms for balance-of-payments adjustments. With a floating rate, a central bank sets a monetary policy but has no exchange-rate policy—the exchange rate is on autopilot. In consequence, the monetary base is determined domestically by a central bank. With a fixed rate, there are two possibilities: either a currency board sets the exchange rate but has no monetary policy—the money supply is on autopilot—or a country is “dollarized” and uses a foreign currency as its own. In consequence, under a fixed-rate regime, a country’s monetary base is determined by the balance-of-payments, moving in a one-to-one correspondence with changes in its foreign reserves. With both of these free-market, exchange-rate mechanisms, there cannot be conflicts between monetary and exchange-rate policies, and balance-of-payments crises cannot rear their ugly heads. Indeed, under floating- and fixed-rate regimes, market forces act to automatically rebalance financial flows and avert balance-of-payments crises.

Fixed and pegged rates appear to be the same on the surface. However, they are fundamentally different: pegged-rate systems often employ exchange controls and are not free-market mechanisms for international balance-of-payments adjustments. Pegged rates require a central bank to manage both the exchange rate and monetary policy. With a pegged rate, the monetary base contains both domestic and foreign components. Unlike floating and fixed rates, pegged rates invariably result in conflicts between monetary and exchange-rate policies. For example, when capital inflows become “excessive” under a pegged system, a central bank often attempts to sterilize the ensuing increase in the foreign component of the monetary base by selling bonds, reducing the domestic component of the base. And, when outflows become “excessive,” a central bank attempts to offset the decrease in the foreign component of the base by buying bonds, increasing the domestic component of the monetary base. Balance-of-payments crises erupt as a central bank begins to offset more and more of the reduction in the foreign component of the monetary base with domestically created base money. When this occurs, it is only a matter of time before currency speculators spot the contradictions between exchange-rate and monetary policies (as they did in the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98) and force a devaluation or the imposition of exchange controls. Like the big devaluations during the Asian financial crisis, the same contradictions tangled up Argentina’s Convertibility System, which was not a currency board, and resulted in a maxi-devaluation and chaos.

So, forget pegs. They will always fail. What about floating? As a means to smash hyperinflation in a country in which no institutions have a semblance of credibility, floating would be a disaster. Just look at what happened to Indonesia during the Asian financial crisis. On the advice of the International Monetary Fund, Indonesia floated the rupiah on August 14, 1997. But, the rupiah didn’t float on a sea of tranquility—it sank like a stone. In consequence, inflation soared, and food riots ensued. These events ultimately forced Suharto out of office on May 21, 1998.

Currency boards have always worked to smash inflation and establish stability. I know. I have designed and helped to install currency boards in Estonia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Currency boards not only work, but they also have an impressive theoretical pedigree. The late Nobelist Sir John Hicks made that perfectly clear. According to Hicks, the currency board rests soundly on the strand of classical monetary theory developed by David Ricardo (1772-1823). As Hicks put it, “On strict Ricardian principles, there should have been no need for Central Banks. A currency Board, working on a rule, should have been enough.”

Those Ricardian principles were put into practice in 1849, when the first currency board was established in Mauritius. Since then, there have been over 70 currency boards operating in most parts of the world. Although ignored by most observers, their rich history has been overwhelmingly characterized by success. Even in the most trying times, currency boards always produce stable money and maintain full convertibility. Countries with currency boards also keep their fiscal houses in order and realize respectable economic growth rates. In addition, they foster stable banking systems in which financial crises are rare. As Hicks recounts, at the zenith of currency boards, early in the 20th century, “The financial cycle was almost disappearing.”

Alas, even an allusion to this exemplary historical record is absent from most of the contemporary literature, including Hausmann’s “National Plan: the Day After.” Venezuela’s opposition must take note before its fingers are burnt.

By Steve H. Hanke

www.cato.org/people/hanke.html

Twitter: @Steve_Hanke

Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics and Co-Director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Prof. Hanke is also a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C.; a Distinguished Professor at the Universitas Pelita Harapan in Jakarta, Indonesia; a Senior Advisor at the Renmin University of China’s International Monetary Research Institute in Beijing; a Special Counselor to the Center for Financial Stability in New York; a member of the National Bank of Kuwait’s International Advisory Board (chaired by Sir John Major); a member of the Financial Advisory Council of the United Arab Emirates; and a contributing editor at Globe Asia Magazine.

Copyright © 2019 Steve H. Hanke - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

Steve H. Hanke Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.