The Bottled Water Bamboozle

Commodities / Water Sector Dec 03, 2018 - 03:46 PM GMTBy: Richard_Mills

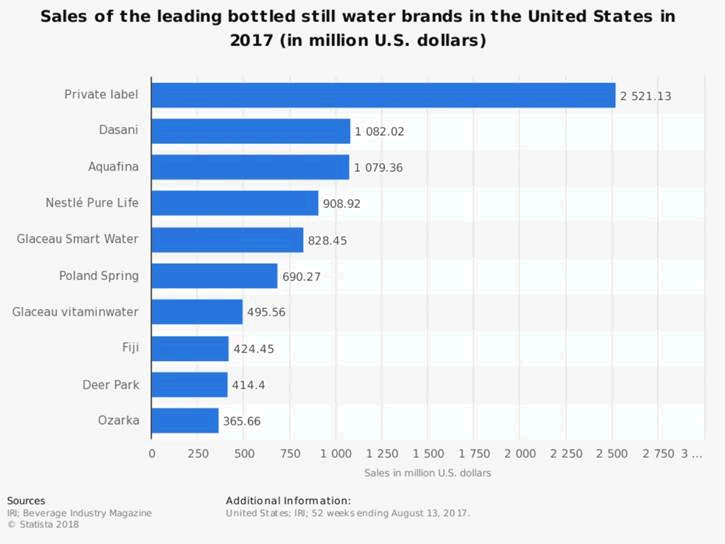

Bottled water is now the most consumed drink sold in a plastic bottle in the United States. The fact that North Americans don’t think twice about paying up to $5 for a bottle of H2O has allowed Nestle Waters - the largest bottled water company in the world - to sell $7.4 billion worth in 2016, and that was just for water, one of dozens of products from chocolate to baby food marketed by the Swiss food and beverage conglomerate.

Bottled water is now the most consumed drink sold in a plastic bottle in the United States. The fact that North Americans don’t think twice about paying up to $5 for a bottle of H2O has allowed Nestle Waters - the largest bottled water company in the world - to sell $7.4 billion worth in 2016, and that was just for water, one of dozens of products from chocolate to baby food marketed by the Swiss food and beverage conglomerate.

Perhaps if Canadians and Americans knew what drilling for water, pumping it to the surface, and piping it to a bottling plant was doing to the world’s groundwater supplies, not to mention the world’s oceans where a lot of the plastic ends up, they would switch to the tap. Incidentally, tap water costs Canadians on the order of tenths of a cent per liter.

The bottled water industry is BIG and growing. Globally, it is estimated to be worth around $170 billion. In Canada the industry generates $2.5 billion in annual sales. In the US, sales reached $16 billion in 2017 - 10% higher than 2016.

No surprise there. Consider the margin on a bottle of a water. Even when the expenses to pump, pipe, bottle and distribute it are taken into account, the cost per unit is very low compared to the selling price. Companies pay next to nothing for the water they draw from underground aquifers, if they’re not just using city water, treating it and passing it off as something exotic.

This article will take a look at this highly profitable but unethical industry that has duped literally billions of people into believing that bottled water is better for you and worth paying top dollar for. Of course, sometimes bottled water is necessary where clean tap water is unavailable. We’re exempting those folks, since they don’t have a choice in the water they drink. We’ll also do a global survey of the state of the world’s aquifers, to show just how much of a risk water boards are taking in allowing multinational companies to deplete billions of gallons/ liters of a scarce fresh water resource. We are truly being bamboozled.

Water exploitation

The top three bottled water companies are Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Nestle. Coke also owns Dasani, a popular brand. There are numerous examples of the big three being blamed for water shortages in areas that are already water-stressed. Some of the objections have resulted in court cases with multi-million-dollar damage payouts.

Coke for example has been accused of drying up communities and farmers' wells to feed its bottling plants, thus destroying local agriculture. It takes almost three liters of water to make one liter of Coca-Cola.

The company’s negative impacts on water have been particularly felt in India - one of the most water-stressed nations on Earth, according to aNASA satellite study. Backlashes have been organized in several Indian states including Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala and Maharastra.

In arid Rajasthan, Coke set up a plant in 2000. Official documents from the government’s water ministry show stable water levels between 1995 and 2000, but the levels dropping 10 meters over the next five years. In the southern state of Kerala a Coca-Cola bottling plant was shut down in 2004 on grounds that it had over-used and contaminated local water sources. The state later passed legislation allowing Coca-Cola to be sued for as much as $47 million.

A similar conflict occurred 10 years later in the city of Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, where Coke was ordered to shut down its plant following complaints that it was drawing excessive amounts of groundwater and it was found to have violated its operating license.

In 2017 over a million traders boycotted carbonated drinks after claims from two Indian trade associations that foreign firms were exploiting water resources. Their concerns were brought to light following low rainfall during the monsoon season, which led to a drought in Tamil Nadu.

Bottling soft drinks is especially problematic in India considering that companies are competing with farmers for water and many regions are parched. Not only that, it takes sugarcane to extract sugar to make pop, and sugarcane is very water-intensive. The director of India Resource Centre, an NGO, told The Guardian it takes 1.9 liters of water to make a bottle of Coca-Cola. But when combined with the amount of water used to grow sugarcane, it’s more like 400 liters to make one liter of Coke.

In El Salvador the world’s largest beverage maker was accused of exhausting water over a period of 25 years, and in Mexico, the government led by former President Vicente Fox - a past Coca-Cola president - reportedly gave the company concessions to exploit local water resources.

In North America, bottled water companies have clashed with local interests in California, Michigan, Ontario and British Columbia. The measly amounts these companies pay for groundwater is at best unethical, at worst criminal.

Take Michigan as an example. The water-rich state (surrounded by four Great Lakes) charges water bottlers just $200 in administrative fees a year. How do they get away with it? It goes back to British common law. The “reasonable use” doctrine allows landowners to use the water on or under their properties so long as it doesn’t affect neighboring ground or surface waters. The principle underpinning the doctrine is that nobody “owns” the groundwater. The problem is this leads to a “tragedy of the commons” situation, where users sharing resources act in their own interests not the interests of the common good.

Michigan Live reports that this same legal principle is applied not just in Michigan, but most states east of the Mississippi. Maine charges $50 per million gallons, Maryland gives it away for free. Only 18 states tax water-bottling factories.

A nine-year court battle against Nestle resulted in a 2009 settlement that limited Nestle to pumping just over 200 gallons per minute from its four wells near Canadian lakes in Mecosta County, Michigan. The company wanted 400 gpm.

In 2017 Nestle got itself into a fight with a Michigan township over its plan to pump 794 millions of liters of groundwater annually (1,500 liters a minute) for bottled use.

Californians are also unimpressed with the Swiss food and beverage titan. Despite experiencing the worst drought since the 1400s, Nestle took advantage of there being no laws on the books in California to draw water from multiple Indian reserves, California currently has 108 bottled water plants.

To bottle its Arrowhead brand using water from Strawberry Creek in the San Bernadino National Forest, Nestle pays the forest service $524 a year; the water rights cost nothing due to a 19th century possessory claim, according to a feature article in Los Angeles Magazine. In 2015 Nestle’s 12 wells pulled 36 million gallons from Strawberry Creek. Activists filed a lawsuit. The suit was recently resolved, with Nestle being granted a three-year water extraction permit, albeit with restrictions that will keep a creek flowing for other uses.

In Canada Nestle has clashed with activists in southern Ontario, near Guelph. Nestle Waters Canada has a permit to take up to 3.6 million liters a day from its well at Aberfoyle but in 2015 opponents urged the province not to renew its license. They claimed the extraction wasn’t sustainable, given that the area was in a drought, and also noticed the aquifer had dropped 1.5 meters between 2011 and 2015 when Nestle had increased its pumping rate by a third.

The Ontario government has come under fire for setting its rates too low for commercial groundwater extraction. The rate used to be $3.71 per million liters (yes you read that right) but in 2017 it went up to $503.71. Water bottlers got a pass until the new rate came into effect, with Ontario allowing them to pump 7.6 million liters a day on expired permits, “as it gives them time to amend renewal applications,” CBC reported.

If you think that’s bad, in British Columbia, the former Liberal government was thrown down a well by the public in 2015 - a drought year also in BC - for giving away water to Nestle for far too cheap. Premier Clark ordered a review of water rates charged after 200,000 people signed a petition complaining about Nestle being allowed to bottle 265 million liters of BC water for - wait for it - $596.25 a year.

Going upmarket

In case you haven’t noticed when you grab a bottle of water at the airport for your flight, the choices have greatly expanded, along with prices. Coke and Pepsi are reportedly bottling higher-end water to compete with industry stalwarts like Evian and Perrier, and introducing fizzy and fruit varieties. Two such brands, Lifewatr and Smartwater, sell for $2.79 per one-liter bottle at 7-Eleven in New York, compared to $1.50 for 7-Eleven’s brand of the same size.

The ever-expanding Chinese middle class is a popular target market for these more expensive bottles. Coke reportedly launched a Swiss brand of sparkling water that is double the cost of a Starbucks venti (extra large) cappuccino. Its Valser water, also said to be sourced in Switzerland, apparently costs US$9.29 a bottle.

Premier brands are also being launched in India, where they are seen as a status symbol, including Coke’s ultra-elitist-sounding Glaceau Smartwater.

Just for fun, take a look at the 10 most expensive bottled waters in the world, ranging from $5 per 750-ml bottle, to an outrageous $60,000 for Acqua di Cristallo Tributo a Modigliani, which comes in a 24-karat gold vessel.

“Bottled water is almost 2,000 times more energy intensive to produce than tap water A research study from 2009 suggests that producing bottled water requires between 5.6 and 10.2 million joules of energy per liter, depending on transportation factors (a typical personal-sized water bottle is about 0.5 liters). That’s up to 2,000 times the energy required to produce tap water, which costs about 0.005 million joules per liter for treatment and distribution. The same research paper estimates that 50 million barrels of oil are dumped into the creation of a year's worth of plastic water bottles (a number that has probably gone up since the research was conducted). Another sources estimates that the amount of oil used to make a year's worth of bottles could fill one million carsfor a year.” WaterDocs,10 outrageous facts about bottled water we need to take seriously

Not so pure

If the quality of bottled water was so much better than tap water, there would be some justification for paying a premium for it. But a little research shows this isn’t the case. Unlike publicly supplied water, which is subject to regular scrutiny, bottled water is not subject to the same guidelines. In fact bottled water in Canada is classified the same as food which is governed by the Food and Drugs Act, meaning it only needs not to contain “poisonous or harmful substances.”

The bottled water industry is estimated to be worth nearly $200 billion a year, surpassing sugary sodas as the most popular beverage in many countries. But its perceived image of cleanliness and purity is being challenged by a global investigation that found the water tested is often contaminated with tiny particles of plastic.

"Our love affair with making single-use disposable plastics out of a material that lasts for literally centuries — that's a disconnect, and I think we need to rethink our relationship with that," says Prof. Sherri Mason, a microplastics researcher who carried out the laboratory work at the State University of New York (SUNY). CBC.com

Studies suggest disposable, plastic water bottles can harbor hundreds of tiny bits of plastic, and we're drinking them down with bottled H2O

Between 2000 and 2009 there were 29 recalls of bottled water products due to contaminants, which included bacteria, mould, arsenic and glass. People are taking more of a risk drinking bottled water than tap water.

And what of those delicious-sounding adjectives, like “spring water”, “artesian water”, “glacier-fed” etc.? According to CBC, unless the water is labelled spring water or mineral water, the companies don’t have to reveal its source. In the US, an estimated 45% of bottled water is actually tap water that has been treated with additives. A class action lawsuit against Nestle, which labeled its Poland Spring water as “naturally purified spring water” when in fact it was from groundwater, was settled out of court, with the multinational agreeing to pay $10 million.

In 2004 Coca-Cola was scandalized when the UK launch of its Dasani brand was tarnished by a reporter’s finding that Dasani was in fact upgraded tap water. Making matters worse, a bad batch of minerals contaminated production, and Coke was forced to pull all half a million bottles in circulation off shelves.

How much water do we have?

The bottled water companies would like you to believe that while the amount of underground water (and tap water) they are using sounds egregious, it is in fact small compared to the water used for irrigation and other purposes, in the country they are operating in.

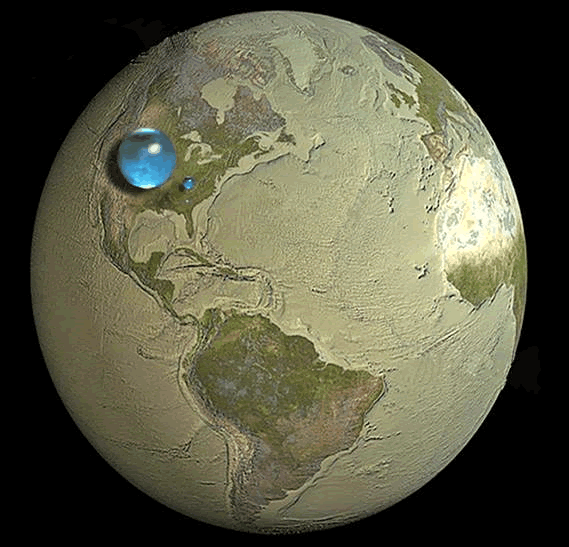

The problem with this argument is that the planet’s fresh water is - contrary to popular notions - extremely limited. We have written on this several times before, but here are the facts again, this time from the US Geological Survey (USGS). The photo of the globe below with the blue circles makes it easy to visualize.

All the water on Earth makes up 1.386 billion cubic kilometers. Almost all of it, 96.5%, is seawater.

More than 2 billion people lack safe drinking water. That number will only grow

The large blue sphere on the map represents not just seawater but water locked in ice caps, glaciers, lakes, rivers, groundwater, in the atmosphere, in soil, and even in living beings.

Now look at the blue sphere over Kentucky. This represents all the world’s fresh water. It is 10.633 million cubic kilometers, or 3.46% of the planet’s total water.

But much of this water is unusable - swamp water, soil moisture, saline groundwater/ lakes, or locked up in ice caps, glaciers, ground ice and permafrost. This leaves just 0.78% of usable water; of this, fresh groundwater makes up 0.76%. Put another way, of all the water on Earth, less than 1% is stored underground, and this precious water is being tapped furiously by bottled water companies and oil and gas companies who use it for fracking.

Each fracking well uses between 1.5 and 15 million gallons of fresh water. This is water that could be used for drinking, by animals or humans, or for irrigating crops and pastures. Billions of gallons of fresh water are destroyed in the process of mixing water with chemicals and frack sand to break apart layers of shale rock to extract oil and gas.

Thirty to 40% of the fracking fluid is left in the well. The “flowback liquid” that is left after the gas is extracted contains water and a number of contaminants, including radioactive material (like radium, which can cause leukemia), heavy metals, hydrocarbons, bromide and other toxins.

The wastewater pumped underground goes into oil and gas waste wells or saline aquifers. There are serious concerns about the ability of these caverns and aquifers to handle the increased pressure and the evidence is showing that deep-well injecting is linked to the occurrence of earthquakes.

For more read our The real price of LNG

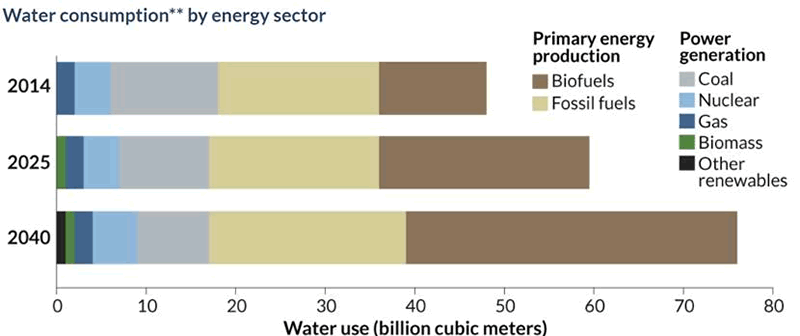

As for what most of the world’s fresh water is used for, it’s mostly to generate power, at least in the United States and Canada. In Canada 34.7 billion cubic meters are used for power generation, mining and manufacturing, farm irrigation uses 1.7 billion cubic meters, and households use 3.2 billion.

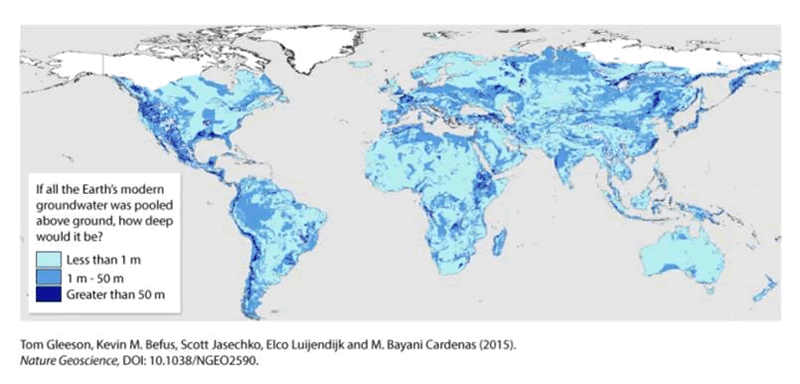

How much groundwater is left?

It may not seem like it living in a place like British Columbia (as I write this the rainfall is biblical) but we are in the midst of a serious fresh water crisis.

Since 99% of Earth’s fresh water is groundwater, this is the most important source to look at in terms of depletion.

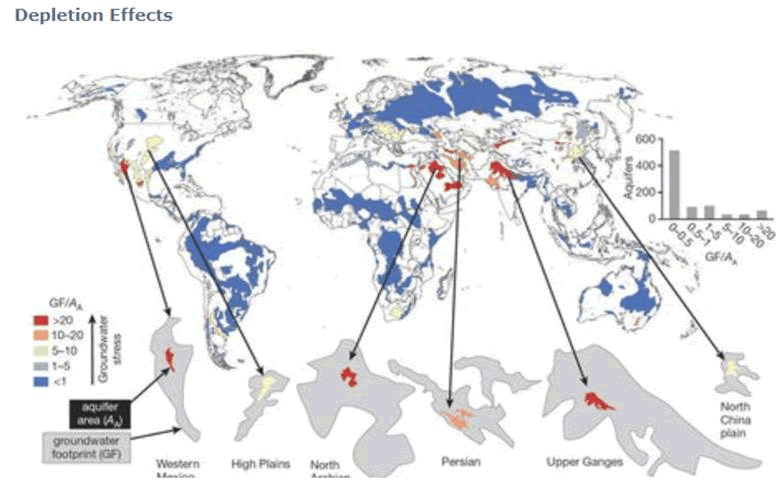

There are two types of aquifers: the shallow kind that get recharged from surface water, and deeper aquifers that contain ancient water that has been locked under the Earth for centuries. Once these non-rechargeable aquifers are gone, they’re gone for good. A University of Victoria study found that just 6% of global groundwater is being replenished within 50 years.

According to the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), we could be looking at a 40% shortfall in the availability of water within just 12 years - that includes the 600 aquifers that cross borders; at current usages, there are sure to be more fights over water in future.

This is happening already. According to the Pacific Institute’s Water Conflict Chronology, in 2017 there were over 70 conflicts over water, compared to just three in 1997. Examples include 70 people killed in Darfur in a clash between farmers and herders; and threats by bandits in India to kill people if they weren’t brought water during a drought.

Of the world’s population of 7.6 billion, 2 billion rely on groundwater. SIWI states that total groundwater withdrawals already exceed availability in about 20% of the world’s aquifers, which provide 35% of the planet’s fresh water.

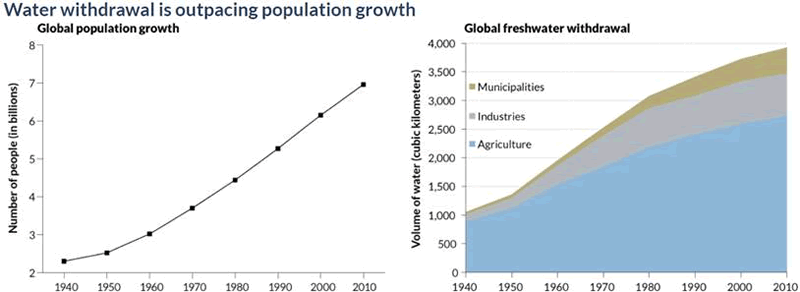

It gets worse. As aquifers are depleting, demand for water is growing. It’s expected to increase 55% by 2050 - mostly due to the need for more food production. Demand increases during droughts, when surface water gets dried up first. California for example, in a drought since 2011, currently taps aquifers for 60% of its water, 20% more than normal.

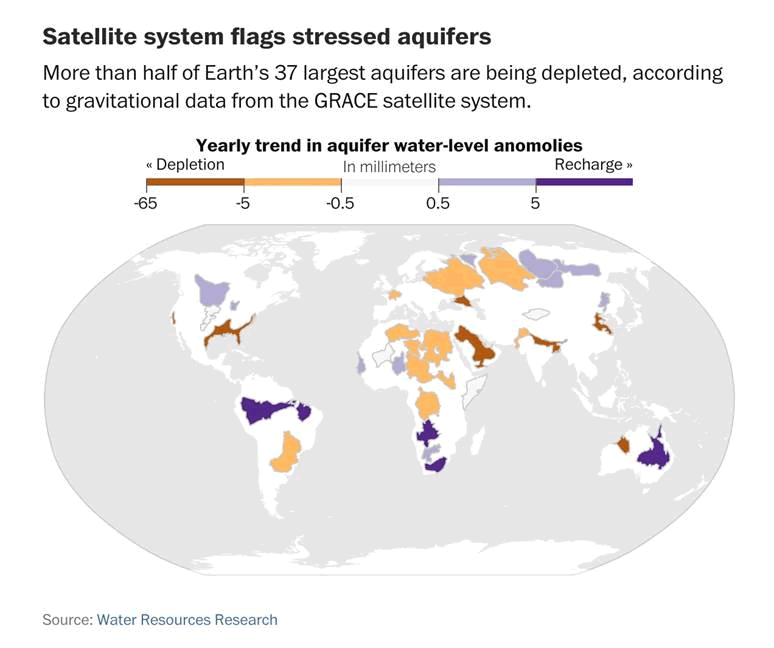

So how are the world’s aquifers doing, region by region? NASA attempted to answer this question using satellite data. It found that of the major gravel and sand-filled aquifers, 21 out of 37 (56%) are receding. A third were described as “highly stressed,” “extremely stressed” or “overstressed”. SIWI states that nearly half of the world’s aquifers may be past their tipping point, meaning a natural recovery has become impossible.

“The water table is dropping all over the world. There’s not an infinite supply of water,” says Jay Famiglietti, senior water scientist at NASA. Falling water tables also lead to increased electricity costs to pump the water up from deeper down.

The most water-stressed aquifers, according to the NASA study and a very recent survey by the SIWI, are:

- Arabian Aquifer, used by over 60 million people across the Arabian Peninsula; 90% of the groundwater is pumped for agriculture.

- Indus Basin in India and Pakistan. Home to 300 million people, the Indus Basin has seen the water table in some parts drop as much as 20 feet.

- Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin, encompassing India, China, Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan, holds 10% of the world’s population.

- Murzuk-Djado Basin in northern Africa.

- Northwest Saharan Aquifer, flowing under 60% of Algeria, almost a third of Libya and part of Tunisia.

- Nubian Aquifer System, also in northern Africa, is the largest non-rechargeable aquifer in the world. It spans Egypt, Libya, Sudan and Chad.

- Canning Basin, Australia.

- North China Plain Aquifer, where about 11% of the Chinese population lives, including the capital Beijing.

- Central Valley Aquifer, California - the most troubled aquifer in the United States. The current drought is forcing farmers to drill wells into the aquifer for irrigation. The Central Valley Aquifer irrigates 25% of all food produced in America.

- Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains Aquifer, along the southeast US coast and Florida.

The red area on the above map (click on map to biggie size) is the aquifer, the grey area is the size of the area that would be required to catch enough rainfall to replenish that aquifer and make up for all the water currently being pumped out of it.

Conclusion

It doesn’t take a hydrologist to figure out that the world must stop bottled water companies from drawing down already-stressed aquifers, or even pumping from areas that aren’t water-stressed. When multinationals like Nestle and Coca-Cola are allowed to sink wells into aquifers for nothing or next to nothing, there’s something seriously wrong.

The problem stems from governments and their representatives being unaware of the fragility of our global groundwater. They don’t know, or don’t care, that we have a crisis of fresh water. Less than 1% of the Earth’s water is groundwater.

Billions of people rely on it for survival. Yet the world’s aquifers are rapidly depleting. We could be 40% short of water in just 12 years. And the demand for water keeps rising. How are we going to meet it? Our current rates of depletion are unsustainable. But if we did one thing to slow the depletion of groundwater, it might buy us a few more years: ban bottled water companies from extracting it.

It doesn’t matter whether the company is pumping it from bone-dry California or rain-soaked BC, eventually we are going to need this groundwater when the Earth warms to the point where all the glaciers melt and once-mighty rivers are reduced to trickles. Instead we’re giving it away. What are we doing?

By Richard (Rick) Mills

If you're interested in learning more about the junior resource and bio-med sectors please come and visit us at www.aheadoftheherd.com

Site membership is free. No credit card or personal information is asked for.

Richard is host of Aheadoftheherd.com and invests in the junior resource sector.

His articles have been published on over 400 websites, including: Wall Street Journal, Market Oracle, USAToday, National Post, Stockhouse, Lewrockwell, Pinnacledigest, Uranium Miner, Beforeitsnews, SeekingAlpha, MontrealGazette, Casey Research, 24hgold, Vancouver Sun, CBSnews, SilverBearCafe, Infomine, Huffington Post, Mineweb, 321Gold, Kitco, Gold-Eagle, The Gold/Energy Reports, Calgary Herald, Resource Investor, Mining.com, Forbes, FNArena, Uraniumseek, Financial Sense, Goldseek, Dallasnews, Vantagewire, Resourceclips and the Association of Mining Analysts.

Copyright © 2018 Richard (Rick) Mills - All Rights Reserved

Legal Notice / Disclaimer: This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified; Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.