Why Philippines Economy Is Thriving, Despite IMD

Politics / Asian Economies May 29, 2018 - 09:36 AM GMTBy: Dan_Steinbock

According to the 2018 IMD World Competitiveness report, Philippines ranking plunged nine notches. In reality, competitiveness indexes often fail to capture disruptive change.

According to the 2018 IMD World Competitiveness report, Philippines ranking plunged nine notches. In reality, competitiveness indexes often fail to capture disruptive change.

According to the IMD report, executed in cooperation with the Asian Institute of Management, Philippines fell by nine places to 50th among 63 countries.

Nevertheless, Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Ernesto Pernia called the findings a “misobservation” - and rightly so.

Economic realities vs. Index data

After the global crisis, the Philippines’ economic performance quickly bounced back, but did not provide sustained growth in the first half of the 2010s. Despite stated struggle against corruption, the Aquino administration neglected systemic graft and drugs proliferation focusing on geopolitics, at the cost of economic development. Investment was ignored. Relatively low debt benefited mainly the financial elite.

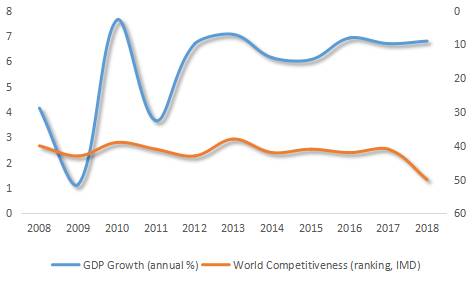

How were these trends depicted by the IMD at the time? Actually, the IMD data suggests nothing much happened in the Philippines in the early 2010s (Figure).

Figure Philippine Economic Performance Vs IMD Ranking, 2008-2018

Source: World Bank (annual real GDP growth); World Competitiveness Index (IMD ranking)

Ironically, the Index ranking also indicates that the country’s competitive performance improved in 2013-14, when narco-corruption grew pervasive creating odd bedfellows in politics. As the Liberal Party saw Manuel Roxas as the next president, a wasteful “election stimulus” supported growth in Aquino’s last days.

In contrast, Duterte began a historical infrastructure investment push, while initiating the requisite changes to boost foreign investment, with his economic team, including Secretary of Finance Carlos Dominguez III, Secretary of Budget and Management Benjamin Diokno and Secretary of Public Works and Highways Mark Villar. That required greater debt-taking and would lead to deficits in the short-term. Philippine peso would soften against the US dollar, as a result of conservative monetary policy in the past and the Fed’s rate hikes. Yet, the Philippines is positioned to enjoy 6-7 percent annual growth and rapidly rising living standards until the early 2020s.

How has the IMD measured these realities? The simple answer is: Poorly. Basically, the Index insulated short-term trends - e.g., debt, deficit, exchange rate - from the transformative investment program, and then mistook its own misreading as the government’s policy mistakes.

As the Philippines is now positioned for sustained growth, the IMD Index suggests that economic performance has been hit the worst, when in fact it is more sustained than in years as the government’s infrastructure program is integrating and connecting the country domestically, regionally, and internationally.

So why do the competitiveness indexes often fail to capture transformative change?

Five caveats

In the past 25 years I have been involved with global competitiveness and innovation initiatives, while lecturing and speaking in MBA and Executive MBA programs from New York University’s Stern School of Business and Columbia’s School of Business to Harvard Business School, Tsinghua and Fudan in China, Singapore Management University, Nanyang Technology University and INSEAD, to mention some.

When the Cold War ended, economic competitiveness came to substitute for geopolitical rivalry. That's when I began cooperating with the leading strategy and cluster analyst, Prof. Michael E. Porter in Harvard Business School. His approach framed the original Global Competitiveness Index by the World Economic Forum (WEF), along with Jeffrey Sachs’s macro index and Xavier Sala-i-Martin’s research.

Of the two competitiveness indexes, IMD’s World Competitiveness Yearbook is the minor one. It deploys both hard data and executive surveys but features only 63 economies. Much of the WEF data is based on executive surveys and a third on hard data, but it features some 140 economies.

The not-so-secret secret of the competitive indexes is that they tend to reflect slowly-changing historical realities. So they often fail to capture rapidly-changing, future-driven and disruptive economic realities, such as Duterte’s transformative leadership.

Second, these rankings rely significantly on executive surveys, which reflect the views of incumbents rather than those of the challengers. When I projected in the US National Interest in 2005 that Chinese and Indian multinationals were becoming competitive and innovative, most observers had not heard of Huawei, Alibaba, Tata and Infosys, and other future leaders. Like the Philippines today, Chinese competitiveness was downplayed for years. Yet, Chinese government leaders and executives remained focused on economic progress - as Filipino leaders do today.

Third, when competitive realities change rapidly and disruptively, hard data is absent and surveys reign. In such situations, domestic media should mirror economic realities. But when that media is linked with domestic monopolies and vested interests, such neutrality is often absent. When Nokia and Ericsson conquered mobile markets in the 1990s, most executives still focused on Motorola and AT&T, which failed in the GSM era - as I discovered advising them in New York City.

Fourth, as most competitiveness indexes represent multinationals headquartered in advanced economies, they offer lessons that don’t always work for late entrants from emerging economies. Last summer, when I spoke in Jollibee’s executive summit, I recalled that when I began to use the company in case studies a decade ago, foreign execs often said: “Jolly, who?” Today, Jollibee is far better known, thanks to its international strategy and quest for excellence.

Finally, there are political linkages behind all indexes. Michael Porter became more widely known in the 1980s, when the Reagan administration made him the head of its competitiveness commission. Jeffrey Sachs’s ideas of “shock therapy,” which monetarist Milton Friedman had first applied during Pinochet's Chilean dictatorship, contributed to Russia’s Great Depression in the 1990s. Sala-i-Martin used to cooperate with Robert Barro who built his growth theory on neoclassical economics, which has been the cornerstone of post-Cold War US administrations. But what works for US dominance may not always be good for other nations.

The long and short of it is that many competitiveness indexes look into the future by staring at the rear-mirror. That’s not a receipt for future , but for crashes.

It is not the Philippine economic performance that is failing. Rather, it is the competitiveness indexes that fail to capture the country’s new economic progress - for now.

Dr Steinbock is the founder of the Difference Group and has served as the research director at the India, China, and America Institute (USA) and a visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more information, see http://www.differencegroup.net/

© 2018 Copyright Dan Steinbock - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

Dan Steinbock Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.