An Inflation Indicator to Watch, Part 1

Economics / Inflation Feb 18, 2018 - 03:56 PM GMTBy: F_F_Wiley

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”—Milton Friedman

Have you ever questioned Milton Friedman’s famous claim about inflation?

Ever heard anyone else question it?

Unless you read obscure stuff written for the academic community, you’re probably not used to Friedman’s quote being challenged. And that’s despite a lousy forecasting record by economists who bought into his Monetarist methods.

Consider the following:

- When Friedman’s strict Monetarism fizzled in the 1980s, it was doomed partly by his own forecasts. Instead of the disinflation the decade delivered, he expected inflation to reach 1970s levels, publicizing that prediction in 1983 and then again in 1984, 1985 and 1986. Of course, years earlier he foresaw the 1970s jump in inflation, but the errant forecasts that came later left him wide open to a “clock twice a day” dismissal.

- Monetarists suffered an even harsher blow in 2012, when the Conference Board finally threw in the towel on Friedman’s favorite indicator, removing M2 from its Leading Economic Index (LEI). Generally speaking, forecasters who put M2 in their models are like bachelors who put “live with mom” in their dating profiles—they haven’t been successful.

- The many economists who expected quantitative easing (QE) to wreak havoc on inflation are, of course, on the defensive. Nine years after QE began, core inflation remains below the Fed’s 2% target, defying their Monetarist beliefs.

When it comes to explaining inflation, Monetarism hasn’t exactly nailed it. Then again, neither has Keynesianism, whose Phillips Curve confounds those who rely on it. You can toss inflation onto the bonfire of major events that mainstream theories fail to explain.

But I’ll argue there might be a better way.

In three articles, I’ll try to convince you that we can develop a better theory by interpreting Friedman’s research differently than he did. Maybe you’ll like the theory, or maybe you won’t, but I promise this: the indicator that falls from it has a better record predicting major inflation trends than any other serious indicator I’ve studied. It’s not the only way to think about inflation, but it’s realistic and practical, and I’m interested in the reader reaction.

They Said, Hey Sugar…

Let’s get started with a walk on the wild side—we’ll walk with the renegades in economics who acknowledge the true role commercial banks play in the monetary system, that of creating money from nothing in the process of making loans. By our choice of company, we’re rejecting mainstream economics, including Monetarism and Keynesianism, which call for banks to be mere conduits in the money creation process. I discussed this topic last year in “Learning from the 1980s,” and I’ll summarize the key points below:

- When Friedman and his coauthor Anna Schwartz published their famous research showing a strong correlation between money growth and GDP growth, they and their followers failed to appreciate the importance of money-creating bank loans.

- Instead of allowing that bank lending might explain the historical correlation to GDP, they assumed that the intrinsic characteristics of money—liquidity, stability, and value as a medium of exchange—explained their results, leading them to embrace measures such as M1 and M2.

- But in fact, their seminal research had little to do with M1 and M2, because that data didn’t exist over the full period they studied. Instead, they used a measure that was almost exactly equal to the amount of money banks create when they make loans and buy securities.

- Loan and behold, when the various measures diverged in the 1980s, M1 and M2 lost their correlations to GDP, whereas the original measure studied by Friedman and Schwartz did not.

Confusing?

I’ll say it again in one sentence:

The money measures economists discuss and follow (M1 and M2, primarily) are empirically inferior to the measure they ignore (bank-created money), even though the measure they ignore is responsible for getting them interested in “money” in the first place.

For anyone my age, think Gilda Radner’s creations Emily Litella and Roseanne Roseannadanna, the spoof newscasters who argued passionately about topics that didn’t match the topics given. After being told of the mistake, Litella would end her rant with a simple “nevermind,” whereas Roseannadanna would just keep on talking. The economics profession is more Roseannadanna than Litella (you’ll never hear a “nevermind”), but my recommendation is to forget what you’ve been told about the monetary aggregates and focus instead on bank-created money.

Do Stop Believing

So I’ve channeled iconic characters from both economics and Saturday Night Live, but I haven’t yet drilled down to the inflation rate. In fact, I’ll use this article to expand on the empirical result noted above, which, to my knowledge, isn’t widely known. Once you see how the alternative approach to money works, and how it differs from mainstream economics, I can break out inflation in the next article. But we’ll also need some terminology.

In the past, I used the name “MDuh” for bank-created money, “Duh” referring to the result that the best indicator is the measure Friedman and Schwartz studied, not the measures they popularized. For this article, though, I’ll use “M63,” referring to the year they published their work. We should credit the original monetary maestros for their extensive research, notwithstanding my alternative interpretation, and “M63” should check that box. (Not only that, but “MDuh,” like a Journey song, sounded catchy at first but wore me down after repeated use.)

To choose M63 components, I ask a single question: Is a potential component initiated by a private entity with the legal authority to create money, meaning either a commercial bank or a similar deposit-taking institution? If the answer is yes, I include the component in M63. Otherwise, I don’t. By using only that criterion, I’m estimating the amount of new money banks pump into the economy when they make loans and buy securities. Not surprisingly, M63 correlates almost perfectly with net bank lending—the correlation between 1959 and 2016 was 0.97.

So, M63 growth and net bank lending both correlate with GDP growth, but why?

I would say it’s because banks are the only institutions that create money from nothing when they make loans, meaning their loans inject purchasing power directly into the economy. For loans that aren’t made by banks, purchasing power flows from one party to another without increasing the total (lenders that don’t hold bank charters have to give up their own purchasing power when they deliver loan proceeds). But for bank loans, net purchasing power increases, because banks can make loans without requiring prior saving. Apart from a small allocation of bank capital, banks conjure loan proceeds from thin air—that’s the crux of what their charters allow them to do.

In other words, bank loans are additive to the amount of spending that’s already occurring, and therefore, flow directly into GDP. They might boost real growth or inflation, or both, depending on a variety of factors including how the loan money is spent. But it’s important to remember that the money–GDP correlation is merely a byproduct of a lending–GDP correlation. Bank lending, not money, is the driving force.

Round, Round, Get Around

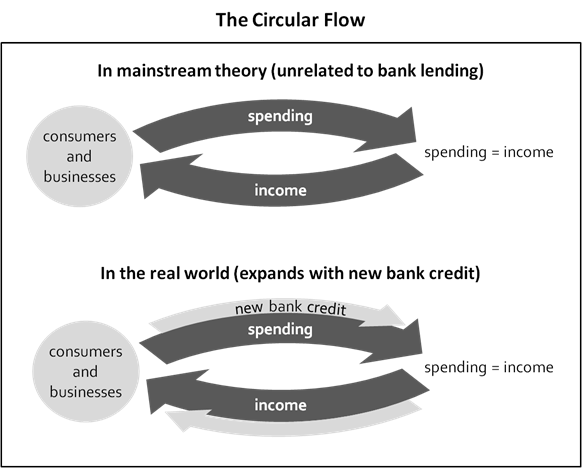

In pictures, we can compare the traditional, mainstream view to the alternative approach by sketching a “circular flow” between spending and income. Here’s an example I’ve simplified from charts that appear in my recently published book, Economics for Independent Thinkers, which covers the topic in more detail:

The upper panel shows that the people on the left—both consumers and businesses—are spending, and because a dollar spent equals a dollar earned, the exact amount that’s spent flows back to consumers and businesses to be spent once again. So money cycles from spending to income and back to spending in a circular flow, and that’s exactly how money works in mainstream theory.

The problem, though, is that mainstream theory assumes the role played by banks to be mostly irrelevant, whereas banks have a giant effect on the circular flow in the real world. In the real world, banks create deposits or cashier’s checks or some other form of money purchasing power to deliver loan proceeds. And by creating money from nothing, they increase spending above and beyond the amount of income that feeds in from the bottom of the loop. The circular flow expands, as in the lower panel.

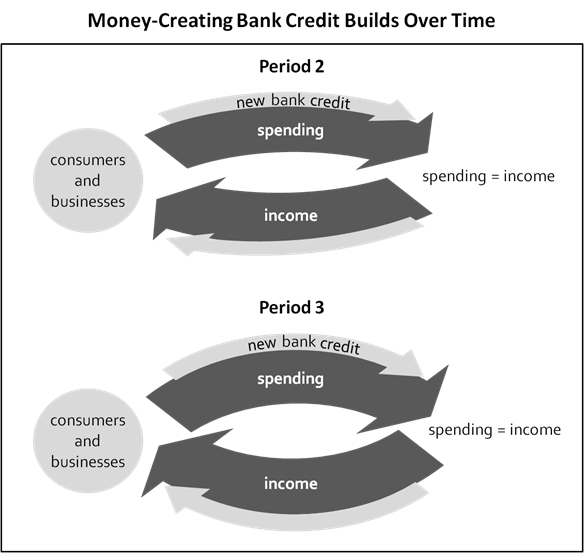

Even more importantly, these bank loan effects cumulative over time. If we say the chart above is the current time period or period 1, then the next chart (below) shows that period 1’s new bank credit (or at least a portion of it) is now part of the circular flow, and then it gets joined by period 2’s new bank credit. And then periods 1 and 2 join period 3’s new bank credit and the flow gets fatter and fatter.

Pictures Telling Stories

If every picture tells a story, the pictures above tell a story of economists building a discipline (mainstream macro) on a false premise so significant it can’t be corrected without starting over. Core theories in every mainstream school rely on the foundational assumption that money is independent of bank lending, all forms of lending believed equivalent and banks believed to be mere intermediaries. Mainstream macro restricts the circular flow to the picture in the first chart’s upper panel—it doesn’t allow private banks to expand the flow endogenously as in the other diagrams.

Of course, some mainstreamers claim to have improved their theories, and almost all of them would rather you didn’t listen to troublemakers like me. According to a typical defense, economists have now figured out how to stuff a hypothetical financial economy into a mainstream, real-economy wrapper, making my criticisms invalid. Anyone who says otherwise just isn’t in-the-know, as the story goes.

I shouldn’t have to write this, but those claims are as hollow as they are self-serving. Every paper I’ve read that purports to fix mainstream theory either still ignores the realities of bank lending or blends in other wildly unrealistic assumptions. (To pick a few notable examples, see Ben Bernanke’s financial accelerator model, similar papers on the same topic or Paul Krugman’s work on the financial economy.) Again, mainstreamers wove false assumptions into the theoretical fabric, and you can’t fix that without shredding the fabric and starting over. And once you’re committed to starting over, as I am, you might borrow from more realistic theories that sit well outside the mainstream.

Too much information?

I digress because certain economists respond predictably to my way of thinking, and it seems a good idea to address the most common response before moving to the next step. If you’re willing to entertain that those economists might be blowing smoke, and I might be onto something, stick with the series for another article.

In Part 2, I’ll extend the charts above to consider other flows relevant to inflation. We’ll need to paint the whole picture before I can present the logic behind my suggested inflation predictor, which, again, has an excellent historical record. Its historical performance might even lead you to question whether inflation really is “always and everywhere” a monetary phenomenon.

F.F. Wiley

F.F. Wiley is a professional name for an experienced asset manager whose work has been included in the CFA program and featured in academic journals and other industry publications. He has advised and managed money for large institutions, sovereigns, wealthy individuals and financial advisors.

© 2018 Copyright F.F. Wiley - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.