Higher US Interest Rates May Force Higher Inflation Rates

Economics / Inflation Sep 15, 2017 - 03:30 PM GMTBy: Dan_Amerman

Summary:

Summary:

1) Financial analysis of the three way relationship between interest rates, inflation and the U.S. national debt.

2) Higher interest rates causing higher interest payments on the $20 trillion national debt would ordinarily cause soaring deficits over time.

3) Detailed analysis of the "loophole", which is that if inflation even moderately increases - then interest rates can rise without exploding the real debt.

4) This simultaneous increase in interest rates and inflation would have a major impact on all markets, as well as long term retirement planning.

5) The logical response to rising interest rates may be to sharpen one's focus on how to better deal with higher rates of inflation over the long term.

Because of the $20 trillion size of the total U.S. national debt, the Federal Reserve acting to increase interest rates would ordinarily create severe financial problems for the government over time, due to sharply rising interest payments on the debt. There is, however, a loophole for the federal government.

As we will examine in this analysis, so long as rates of inflation increase - then the United States government can remain financially healthy while increasing interest rates. Indeed, it could even be said that for heavily indebted nations - higher rates of inflation are mandatory with higher interest rates, all else being equal.

The increase in inflation does not necessarily need to be dramatic, there is no need for hyperinflation or 10%+ annual rates of inflation. However, even a moderate increase in inflation, in combination with a moderate increase in interest rates, is enough to transform investment results in all the major asset categories of bonds, stocks, real estate and precious metals.

The Federal Reserve is currently discussing slowing the planned rate of interest rate increases because of purported low inflation. With that in mind, what this analysis explores is a critical but often-overlooked component of the relationship between interest rates and inflation, that may have a profound impact on Federal Reserve decisions - and therefore the markets - over the coming years.

Because of the particular exposure of retirees to inflation, the governmental need for higher inflation rates to enable higher interest rates may have a dramatic impact on retirement investments and standards of living.

Rising Interest Rates & Governmental Solvency

In the preceding analysis linked here, we examined the effects on U.S. government deficits and the national debt if the Federal Reserve were to carry through with raising interest rates by a total of 2.25% from the post-crisis low.

The conclusions were that over the short term of the next 1-3 years, the weighted average life of the national debt does indeed allow the Federal Reserve a great deal of latitude when it comes to raising interest rates. This is because most of the national debt is not initially impacted.

Within 5-11 years, however, maintaining higher interest rates comes at a very high cost as ever more debt rolls over at the new interest rates, and this would have the effect of doubling the interest payments on the national debt, while drastically increasing the size of the annual deficits.

When we go to the longer term of 15-20 years and beyond, the Fed's stated plans would create a financial catastrophe scenario, because of the higher exponential compounding rate of 4.5% versus 2.25%.

The Inflation Loophole

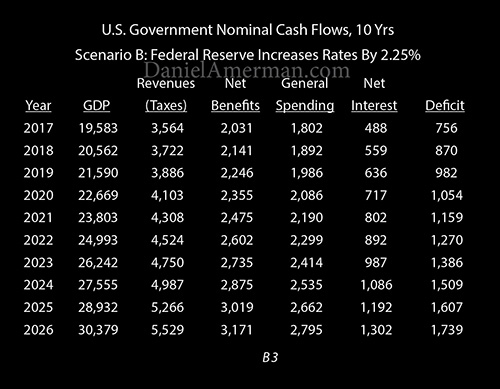

The table above is from the preceding analysis, and it shows how a 2.25% increase in interest rates incrementally increases interest payments over the coming years.

We start with the economy (assuming 2% real growth and 3% inflation), determine tax revenues as a percent of that economy, take out net benefits and general governmental spending as percentages of the economy, then take out interest on the national debt, and that leaves the annual deficit.

The increase in interest rates doubles the interest payments on the national debt by 2023, and helps to approximately double the annual government deficit to over $1.5 trillion per year by 2024.

(In order to tightly focus on the critical but little understood relationship between 1) the national debt, 2) interest rates and 3) inflation, a number of simplifying assumptions were made. The most important is that "net benefits" - the sum of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid - were left constant as a percentage of the economy at fiscal year 2016 levels. This spending is expected to rise dramatically in the coming years, which produces much larger deficits over time than those shown herein.)

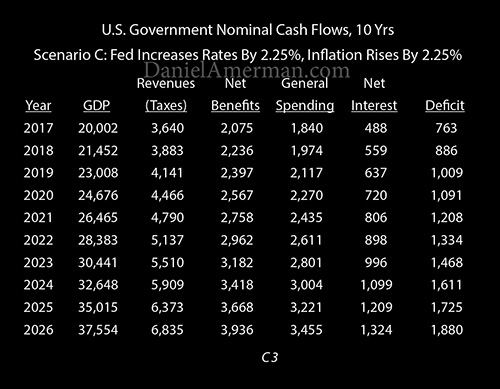

Scenario C is identical to the previous scenario, with one exception. Inflation rises by 2.25%, to 5.25%, in order to offset the 2.25% increase in interest.

If we focus on the net interest and deficit columns, then this might appear to do no good whatsoever. Net interest is up by $22 billion ($1,324 - $1,302) when we go to fiscal year 2026, and the annual deficit is up by $141 billion ($1,880 - $1,739).

How does increasing the deficit by over $100 billion a year help the federal government?

The answer can be seen when we look at the bottom of the GDP and Revenues columns. The higher rate of inflation scenario (C) produces an economy by 2026 that is over $7 trillion a year greater than that produced by the lower rate of inflation scenario (B). The economy isn't really larger - real economic growth is 2% in both scenarios - it is just that higher inflation means that there are a lot more dollars out there, with each of those dollars purchasing less. Keeping taxes constant as a percent of the economy means that taxes increase by over $1.3 trillion per year.

And if taxes are up by over $1.3 trillion per year, but net interest costs are up by only $22 billion per year - then the federal government is indeed in far better financial shape than it otherwise would have been.

Yes, general government spending and "Net Benefits" (Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid) are shown as rising in exact synch with the increase in inflation, so the dollar amount of the deficit does increase. But because taxes rose so much faster, that deficit is actually much more relatively affordable.

Moving To Inflation-Adjusted Dollars

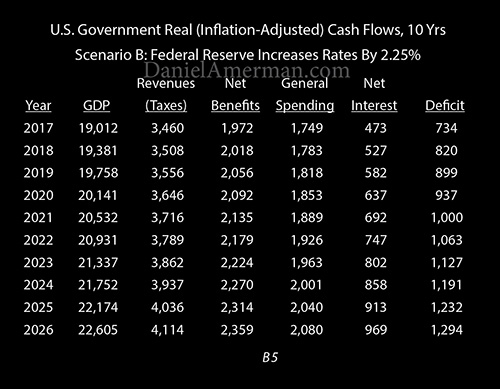

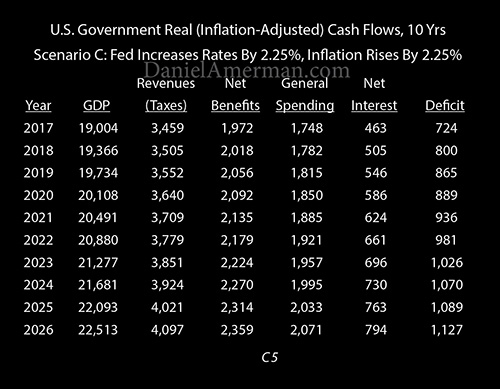

How increasing rates of inflation financially benefit governments with large national debts becomes much clearer when we move to what are known as real or inflation-adjusted dollars, meaning dollars whose value have been adjusted for the changed purchasing power of the dollar.

If interest rates rise but inflation doesn't, then we have inflation-adjusted annual interest payments of almost $1 trillion by fiscal year 2026, and an annual deficit of almost $1.3 trillion.

If inflation also rises, however, then the real value of interest payments falls below $800 billion by 2026, and the annual deficit falls to a little above $1.1 trillion.

This may not like sound like such a big deal, but as shown below, it can be enough to make the difference between ever increasing problems for the government, and an improving situation.

If we look at the size of the national debt versus the economy, then increasing interest rates means a debt that is starting to pull away from the economy, meaning a nation that is getting in ever worse financial shape.

But raising inflation by a corresponding amount means that the national debt is actually pulled down in inflation-adjusted terms, even as the economy continues to grow in size.

What appears to be subtle changes is enough to create a night and day difference. Increasing inflation by a little over 2% is enough to transform the financial health of the government - even as it transforms real investment results, as well as standards of living in retirement.

How Subtle Changes Build Over The Longer Term

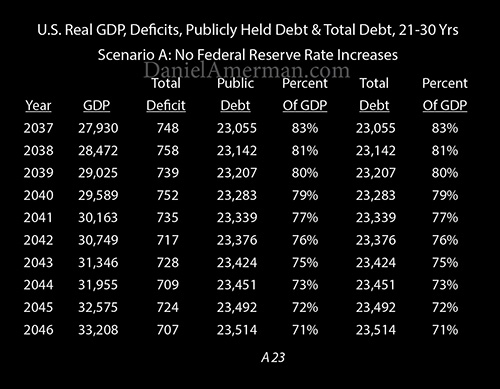

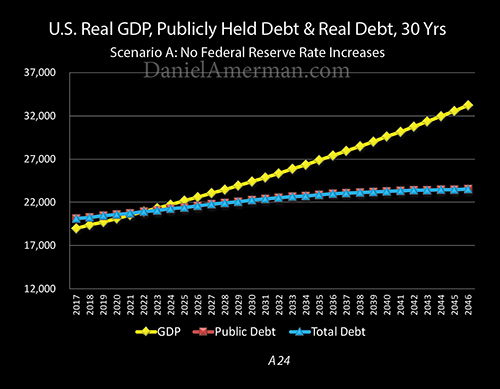

How seemingly subtle changes can transform results over the longer term can be seen in the base "A" scenario above, with 2% real economic growth, 3% inflation and no change in average interest costs for the national debt. The inflation-adjusted value of the national debt in the base scenario climbs to "only" $23.5 trillion by 2046. Because the size of the economy has climbed to over $33 trillion by then, such a debt is much more affordable for the nation than today's $20 trillion debt.

This can be seen graphically above, where the yellow line of the economy grows larger than the debt by the earlier 2020s, and then continues to climb, while the inflation-adjusted value of the national debt languishes in an almost flat range, becoming ever less important.

(Again, this is based on neutralizing the growth in Social Security and Medicare payments, in order to focus in on the crucial but little-understood relationship between the size of the national debt, what income from interest payments can be on a sustainable basis, and what our dollars will buy for us.)

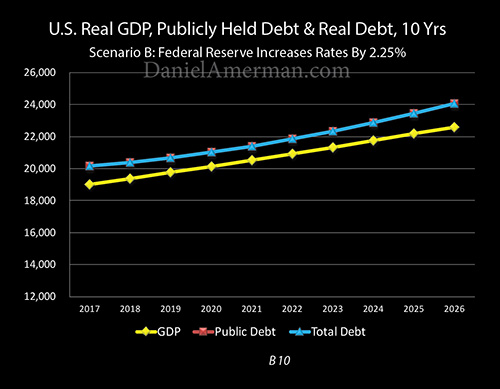

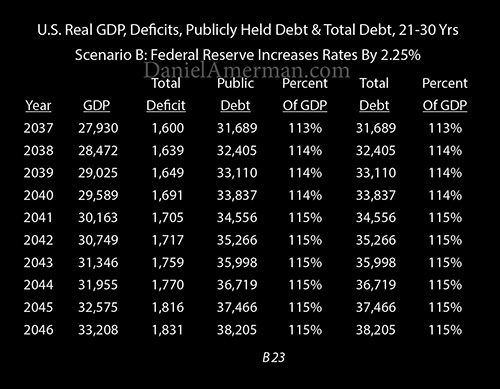

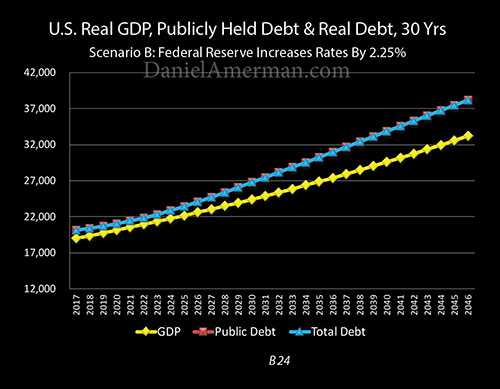

If we assume that the Fed raises rates by 2.25% - but inflation is 3% - then we get the "B" scenario table above, with an inflation-adjusted national debt that almost doubles from today, and is much larger than the size of the economy.

This is shown graphically above, and what we can see is a nation in growing financial trouble.

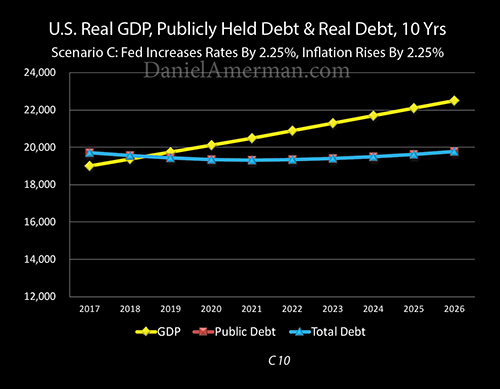

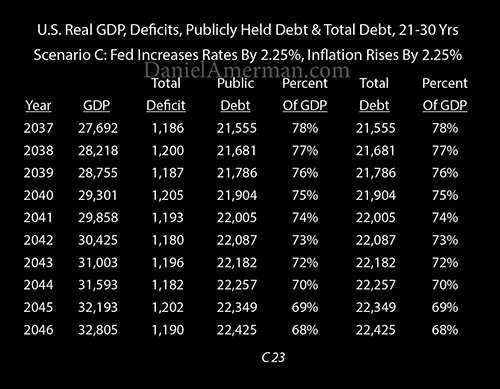

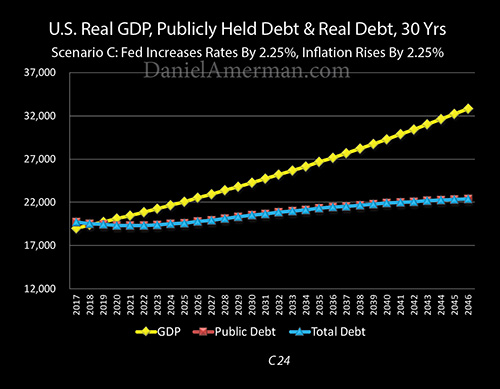

However, if the rate of inflation is also increased by the same amount as interest rates, as explored in the "C" scenario - then the national debt is "only" $22.4 trillion by 2046.

As shown graphically above, increasing inflation at the same time that rates are increased can indeed entirely neutralize the increase in interest rates.

(The "C" scenario with equal increases in inflation and interest rates produces slightly better results than the base "A" scenario because inflation is shown as occurring immediately in the early years, while it takes many years for the national debt to roll over and reprice to higher interest rates.)

Conflicts Of Interest

Many people believe that a $20 trillion national debt is a somewhat abstract problem with little practical impact on their day to day lives or their long-term financial planning.

What they are missing is that heavily indebted nations - like the United States today - have major financial limitations which less indebted nations do not. So when the national debt of the United States quickly doubled between 2007 and 2014 - the challenges associated with long-term investments and retirement financial planning dramatically changed as well.

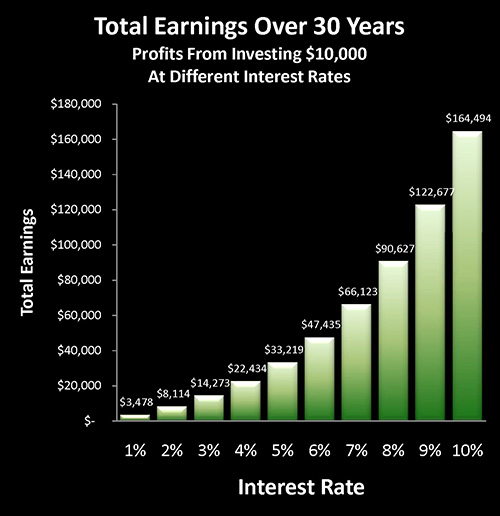

As explored in the analysis linked here, there is a powerful conflict of interest between savers and heavily indebted governments when it comes to interest rates. Savers build wealth when interest rates are on the right side of the graph. Heavily indebted nations maintain solvency by "dialing" rates down to the left side of the graph - which simultaneously destroys investor wealth creation.

So when interest rates collapsed at the same time that the national debt soared - it was no coincidence. There were multiple reasons why the Federal Reserve moved interest rates to historic lows, but one of the most important ones is that both deficits and the debt would have exploded upwards - far beyond where they are right now - if rates hadn't been forced down. Investors who don't take this fundamental relationship into account may be very disappointed with long term investment results, while those who understand it and explicitly build it into their plans may be rewarded.

Inflation is the other basic "dial" that is available for heavily indebted governments. By increasing the rate of inflation - the value of the national debt is steadily wiped out over time. As is the value of the dollar and the value of retirement savings.

Higher National Debts & Higher Interest Rates Require Better Inflation Planning

Inflation has always been the scourge of successful long-term financial planning. It is far more difficult to achieve substantial wealth gains over time in after-inflation and after-tax terms, than it is with simple pre-tax dollars.

Even in ordinary times, this issue is amplified for retirement investors, who will no longer have salaries that (hopefully) keep up with inflation. So they need to find a reliable way to try to overcome the ever declining value of the dollar, and that isn't easy while making safe investments, even with just historically average rates of inflation.

However, when a nation becomes much more heavily indebted - then the inflationary challenge necessarily becomes that much greater for retirement and long-term investors. Because the government now has an extremely powerful motivation to (on average) increase the rate of inflation over time.

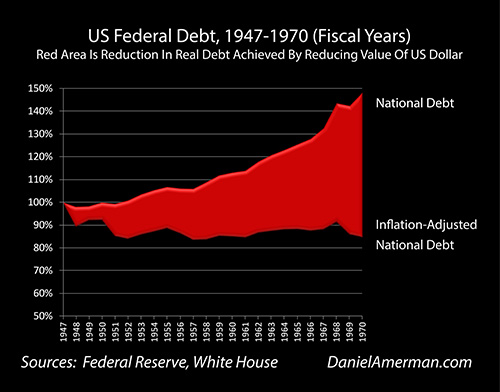

This has happened many times in many nations, and it is fairly basic macroeconomics - heavily indebted nations which control the value of their own currencies create inflation in order to reduce the real value of their own debts.

When people think about using inflation to wipe out national debts, they often jump straight to hyperinflation, and think of examples such as Zimbabwe or Argentina. They assume a false dichotomy where either things are "normal", or it is straight to monetary catastrophe.

However, as explored in the analysis linked here, there is another alternative which is the use of low interest rates and moderate rates of inflation in combination to gain control over the national debt, and this alternative is a key part of the financial history of the United States. Few people understand it today, but for a period of decades both the interest rate and inflation "dials" were twisted to restrain the growth of the national debt (as shown above), while the economy grew, and the nation slowly emerged from its heavy World War II debt burden. Even as the other major economies of the West were doing the same thing.

Yes, this analysis uses simplified projections about the future, in order to illustrate some crucial issues that most people are not taking into account. But the tools themselves are not the slightest bit theoretical, instead they are our collective history, even if little understood.

Now, because this a long-term process, there can be temporary disconnects. Stated inflation can go up and down in a range, and can stay in the lower end for years at a time - particularly when the government controls the calculation of the inflation statistics. But over time, unless there is a major change in economic growth, then a higher rate of inflation for more indebted governments could be called almost a requirement, if financial solvency is to be maintained.

Rephrased, higher national debts mean that inflation planning becomes a much more important component of retirement and other long-term financial planning. That doesn't mean that individuals and planners will immediately realize this, but it does increase the likelihood of a disappointing outcome over the long term, if the plan does not change to address the greater inflationary challenges.

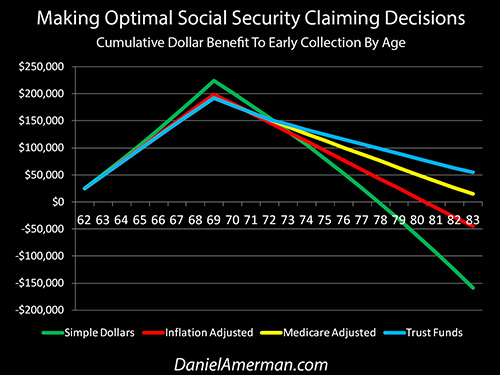

It is also necessary to understand that better inflation planning extends beyond just retirement savings. One of the most important retirement decisions a person can make is when to start claiming their Social Security benefits, as this decision will help determine the size of their monthly benefits for the rest of their lives.

Yet, as explored in the analysis linked here, many Social Security decision aids do not properly take inflation into account, nor how Medicare premiums impact the inflation indexing of Social Security for most recipients. Higher rates of inflation can increase the degree of errors - and the potential negative impact for recipients.

Therefore the greater the potential for future inflation, the more important it is that inflation be built into both sides of the retirement financial planning process, including both savings and benefits.

The Third Level Of Inflation Challenges

There is a third level, which is what we have explored using a very simplified methodology in this analysis. If a nation is heavily indebted AND average interest rates go up over the longer term - then the necessity and the challenge of finding strategies for overcoming inflation goes up right along with the rates.

This is not the current discussion. We have the Fed continuously talking about raising rates, with the variable being how long the process will take. We have widespread investor beliefs that inflation may effectively be "dead", and perhaps may even be as low as 1% per year over the coming decade.

The fundamental problem is that the two of those in combination - higher interest rates and purportedly very low inflation - don't add up for a nation that is $20 trillion in debt. The combination is indeed quite toxic (unless we have a much higher rate of real economic growth), and the resulting surge in the national debt could greatly bring forward in time a financial crisis scenario, that might require slashing Social Security and other government spending.

So either a financial crisis is created that that can entirely change the retirement planning process - or rates must come down, or inflation must go up. Or, both could occur at the same time. And the longer that rates are up or inflation is down, then the greater the chance that there will be an eventual crisis, or the greater the adjustments that must eventually be made in terms of lower rates and/or higher inflation in order to avoid the crisis.

Which is precisely why each time that someone reads a headline about rising interest rates - their response should arguably be to sharpen their focus on how to better deal with higher rates of inflation over the long term.

The perspective developed in this analysis is also very useful information when it comes to interpreting the verbal dance from the Federal Reserve as it goes back and forth on raising rates, and says it is reluctant to raise rates unless it can get inflation to be higher.

Yes, there are plenty of theoretical considerations when it comes to the relationship between interest rates, inflation and economic growth that are difficult to understand (and are possibly not even correct). However, there is also an entirely tangible component that can be understood, and which we just reviewed.

Heavily indebted nations that let interest rates climb while keeping inflation low are in danger of having to borrow ever more money until something breaks. And a crisis of that type is prevented (or at least delayed) by either reversing course and bringing rates back down, or by making sure that inflation goes up, with this being accomplished by potentially taking more drastic actions than those taken to date.

Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Website: http://danielamerman.com/

E-mail: mail@the-great-retirement-experiment.com

Daniel R. Amerman, Chartered Financial Analyst with MBA and BSBA degrees in finance, is a former investment banker who developed sophisticated new financial products for institutional investors (in the 1980s), and was the author of McGraw-Hill's lead reference book on mortgage derivatives in the mid-1990s. An outspoken critic of the conventional wisdom about long-term investing and retirement planning, Mr. Amerman has spent more than a decade creating a radically different set of individual investor solutions designed to prosper in an environment of economic turmoil, broken government promises, repressive government taxation and collapsing conventional retirement portfolios

© 2017 Copyright Dan Amerman - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: This article contains the ideas and opinions of the author. It is a conceptual exploration of financial and general economic principles. As with any financial discussion of the future, there cannot be any absolute certainty. What this article does not contain is specific investment, legal, tax or any other form of professional advice. If specific advice is needed, it should be sought from an appropriate professional. Any liability, responsibility or warranty for the results of the application of principles contained in the article, website, readings, videos, DVDs, books and related materials, either directly or indirectly, are expressly disclaimed by the author.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.