Unintended Consequences, Part 1: Easy Money = Overcapacity = Deflation

Economics / Deflation May 19, 2016 - 06:23 PM GMTBy: John_Rubino

Somewhere back in the depths of time the world got the idea that easy money — that is, low interest rates and high levels of government spending — would produce sustainable growth with modest but positive inflation. And for a while it seemed to work.

Somewhere back in the depths of time the world got the idea that easy money — that is, low interest rates and high levels of government spending — would produce sustainable growth with modest but positive inflation. And for a while it seemed to work.

But that was an illusion. What actually happened was textbook, long-term, surreally-vast misallocation of capital in which individuals, companies and governments were fooled into thinking that adding new factories, stores and infrastructure at a rate several times that of population growth would somehow work out for the best.

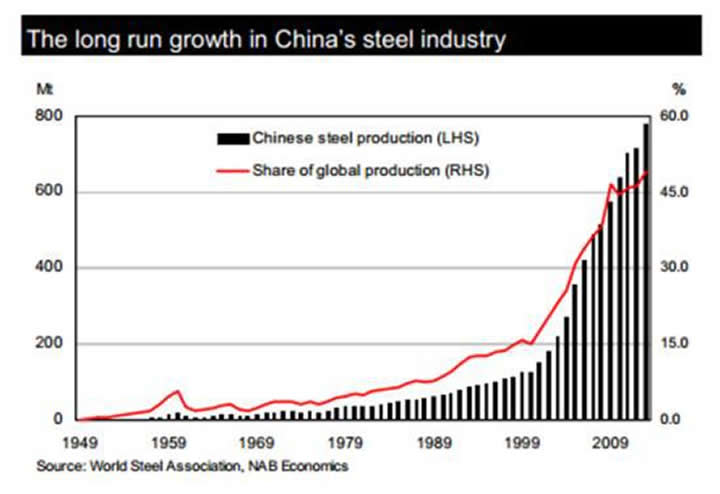

China, as with so many other things, was the epicenter of this delusion. In response to the 2008-2009 financial crisis it borrowed more money than any other country ever, and spent most of the proceeds on infrastructure and basic industry. It’s steel-making capacity, already huge by 2008, kept growing right through the Great Recession, and now dwarfs that of any other country.

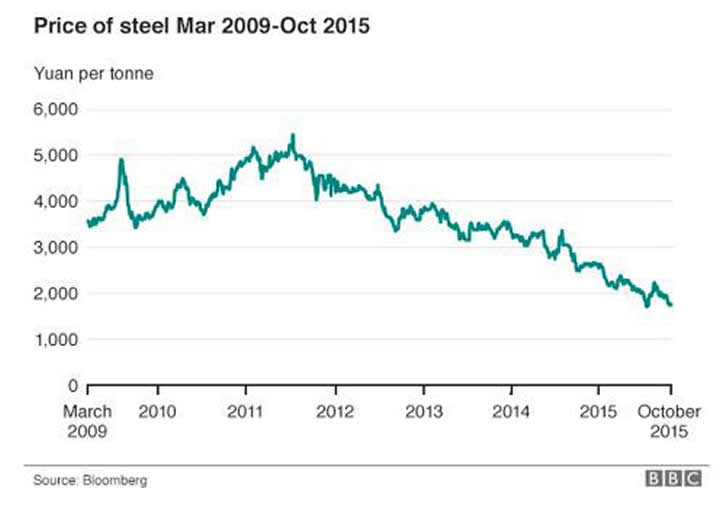

The result was indeed higher prices for iron ore and finished steel up front (that is, the inflation the architects of the easy money era expected and desired). But this was soon followed by falling prices as the rest of the world’s steel makers tried to stay in the game.

It’s the same story pretty much everywhere. Miners that produced the raw materials for the infrastructure/industrial build-out started projects based on inflated price projections and now have no choice but to keep producing to cover variable costs and avoid bankruptcy. Prices of virtually every commodity have as a result plunged.

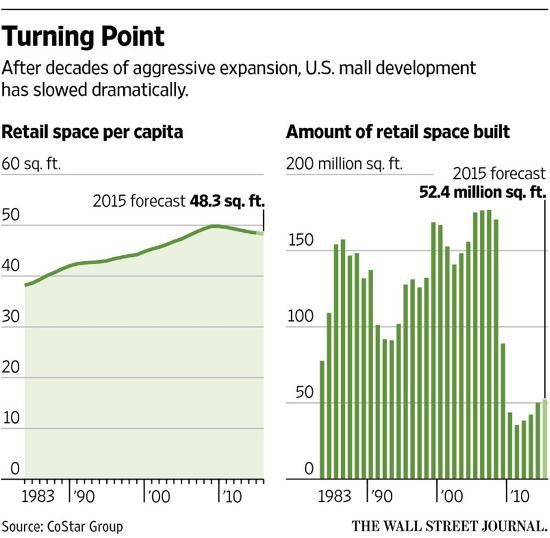

In the US, retailers built new stores at a pace that vastly exceeded population growth, apparently on the assumption that consumers would keep borrowing in order to buy ever-greater amounts of semi-useless stuff. And now bricks and mortar retailing is suffering a mass-die-off.

Even cheese, of all things, is in a potentially disastrous glut:

What does this mean? Several things:

Cheap money sends a “borrow and spend me” signal to the markets, just as expensive money (i.e., high interest rates and government surpluses) says “save and invest me”. So when money is made artificially cheap by cluelessly expansionist governments, it leads people to overborrow and overbuild.

The resulting overcapacity leads to price cuts as marginal producers sell for whatever they can get just to keep the lights on. Falling prices for individual products in the aggregate create systemic deflation. In other words, we’re getting exactly what we should have expected from “inflationary” policies — which is deflation.

The next stage of this process will be either:

The mass failure of marginal players in virtually every basic field. Steel mills, cement factories, shopping malls, high-cost miners, dairy farms, etc., etc., will default on their debt, fire their workers and liquidate their assets, leading to a global depression in which deflation exceeds the 25% seen in the 1930s. Or…

Mass devaluation in which the world’s governments lower the value of their currencies to make their debts survivable. This will, of course, scream “borrow and spend me before I lose even more value” to the markets, thus increasing systemic leverage and producing an even bigger bust somewhere in the future.

We’re clearly opening door number two, so the volatility of the coming decade should put today’s uncertainties to shame.

One final, hopeful note: In both scenarios, real cash, i.e., gold, is king. In the Great Depression, things got cheaper, which made life easier and more fun for people with money. During times of currency devaluation, gold soars in local currency terms — and life gets easier and more fun for the metal’s owners. So either way, owning sound money (as opposed to euros, dollars, yen or yuan) is one part of a plan to survive what’s coming.

By John Rubino

Copyright 2016 © John Rubino - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.