A Visual Look At The Fed Decision From A Retirement Investor's Perspective

Interest-Rates / Pensions & Retirement Apr 01, 2016 - 11:59 AM GMTBy: Dan_Amerman

Below is the transcript for the video. While the images are included below, the motion graphics and use of a pointer are quite helpful for conveying the information, and these can only be seen by watching the video.

Below is the transcript for the video. While the images are included below, the motion graphics and use of a pointer are quite helpful for conveying the information, and these can only be seen by watching the video.

Hello my name is Daniel Amerman, and thank you for joining me.

We are going to take a look using a number of visual images at what has been happening recently with the Federal Reserve, how this integrates with the federal government and the national debt, and the just extraordinary implications when it comes to retirement and other long-term investment decisions.

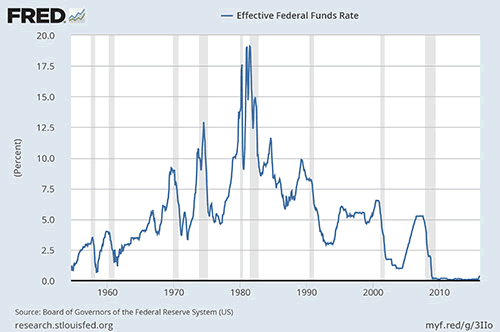

Our starting point is this graph from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, which shows the effective federal funds rate from July 1954 to February 2016.

As you can see it starts off very low in the 1950s and early 1960s, and then it goes in kind of a medium range, we could call them shoulders, between 1965 and the mid-1970s. There's a sharp peak from 1978 to 1982, and then we're back in that shoulder range from the mid-1980s through the late 2000s.

Then between September and December of 2008 during the very height of the financial crisis the rate plunged to almost zero in the space of four months and it has remained there or very close to there in the more than seven years since that time.

Now let's take a look at the dramatic increase in interest rates by the Federal Reserve that occurred in December of 2015 that has drawn such a tremendous amount of scrutiny and media and investment community coverage. But we're going to have to zoom in a bit to see it at all, because so far it has been so very tiny compared to Federal Reserve actions in previous cycles when they had decided to increase interest rates.

What the Federal Reserve originally communicated was that they intended to raise rates five times at about 0.25% each - four times during 2016 and once in 2015. And altogether those would've brought interest rates up from close to 0% to a little bit over 1.25% over the space of a little more than a year.

Which is still very small, very slow if we look at some recent cycles. The Federal Reserve moved interest rates in terms of the effective federal funds rate from 1.0% in May of 2004, to 5.25% in July of 2006, which was an increase of 4.25% in a little over two years.

The cycle before that, the Fed moved from 3.0% in January of 1994, to 6.0% in March of 1995, which was an increase of 3.0% in a little over a year. And of course if we go back to the mid-1970s and to the early 1980s there were far more dramatic rate increases in those times.

So even if the initial goals had been met that, still would've been a very minor increase by historical standards. However what the Federal Reserve has been most recently saying - and they have been changing their minds on a frequent basis there's no guarantees about this - but their current plans are that they might increase rates maybe twice in 2016, at maybe 0.25% each, and if they do indeed follow through that's still going to leave the effective federal funds rate below 1.0% by the end of 2016.

So why are they being so hesitant in seeking an answer?

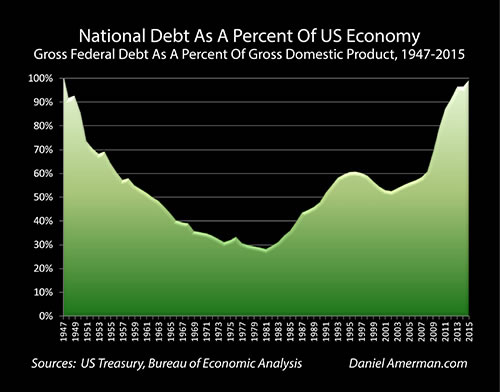

Let's take a look at this graph, which is in many ways the inverse of the interest-rate graph which we just looked at, and I'm going to suggest that that is no coincidence.

What this graphic shows us is the national debt as a percentage of the US economy. And you can see that it started very high, it was roughly equal to 100% of the US economy back in 1947. It was driven downwards, and as my long term readers know, I have extensive materials on how this happened, but it was driven downwards to below 30% by the early 1970s to the mid-1970sand then it started slowly climbing again.

And then we hit the financial crisis of 2008 and the deficit exploded relative to the ability to pay for it - which is relative to the national economy - as attempts were made to contain the economic damage from the financial crisis of 2008.

So let's look again at our interest-rate graph, and then our national debt affordability graph, and put them on screen together. There's a little difference in when they start - 1947 versus 1954 - but they are effectively the inverse of each other.

We have exceptionally low interest rates whenever the national debt is very high in real terms, in terms of affordability, in terms of the size the economy. And interest rates are only allowed to go very high when the national debt is comparatively low compared the national economy.

Those are the exact times where because the debt is much less, that higher interest payments on that debt become affordable.

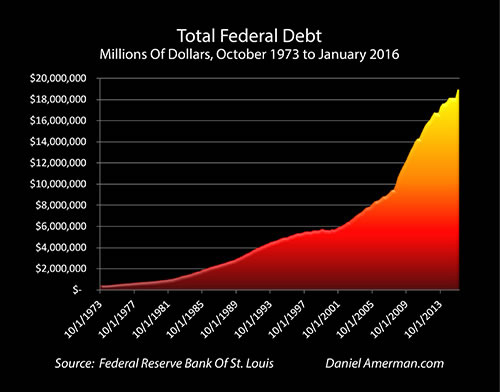

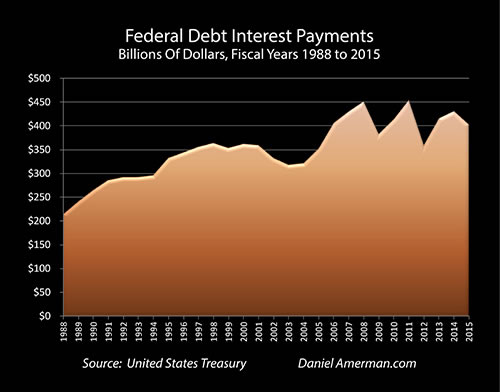

Now let's take another look at the total federal debt - just in dollar terms, we're not looking at compared to the economy anymore, and we see that explosion upwards in debt. Now shouldn't we be seeing an explosion upwards in interest payments on that debt?

But when we look at this next graphic that isn't what is happening at all. Interest payments on the national debt stopped growing, and even went down in some years.

Now let's put both of them up on screen. How could interest payments stay flat or even decline while the national debt was exploding at the fastest rate in US history (outside of a major war)?

This is how!

When we add our third graph of the effective federal funds rate, and move back and forth between them, then we can really start to see what is happening here.

The debt exploded.

Interest rates plunged.

The increase in interest payments that would've otherwise sent the annual budget deficit in the early 2010s up to over $2 trillion year - was cut off and prevented from happening by the Federal Reserve.

So what would happen to annual deficits and the total federal debt if interest rates were to return to more historically normal levels?

The really important relationship to understand is that the United States government currently does not have enough income from taxes to make interest payments on the federal debt, not after paying for everything else in the federal budget. So what the US government does each year is it borrows the money to make those interest payments.

And that has in recent years been the single largest source of the annual deficit for the US government, which has been making interest payments on that very large national debt.

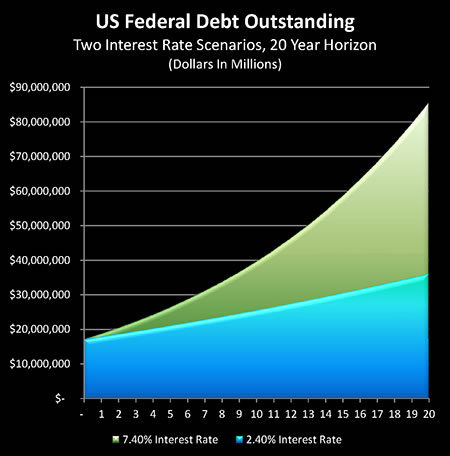

And if we look at this graphic we have two different interest rate levels that are being shown.

The blue area takes a look at what happens if our current interest rate levels stay the same indefinitely. The average interest rate that the US government pays on the federal debt is just a little over 2.4%, and because those interest rates are so low, the interest payments are very low.

And the national debt grows at a much slower pace, we're still up to $30 trillion - which is a big increase from today - by the time we're 20 years out but it is not just explosive.

However if we return to more historically normal interest rates, then we would have to borrow almost another trillion dollars a year to make interest payments, on let's say a 7.4% average interest rate on the federal debt. Which would be much more historically average if we're looking back let's say from today back to the 1950s.

And each year that we borrow that additional trillion dollars to make the interest payments, then our debt rises very rapidly, and the US government - as I've written about in some other articles - very rapidly develops a compound interest problem. So if we were to return to normal historic interest rates, instead of being above $30 trillion in 20 years, we would be above $80 trillion, and we would've passed the point of affordability long before then.

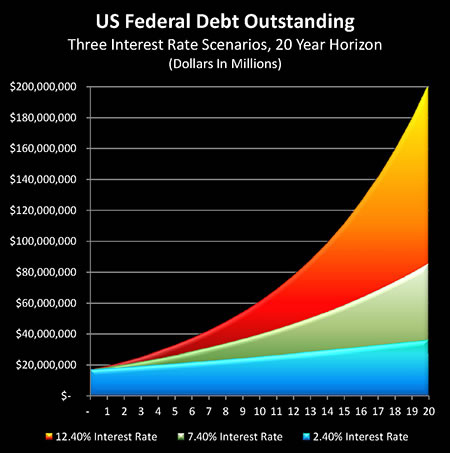

But that is far from worst-case scenario. What happens if the federal government really loses control of interest rates and we experience something like happened in the 1970sand 1980s?

Well if we go up to a 12.4% average interest rate on the national debt, that sets off a compounding of interest that means the national debt explodes upwards to over $200 trillion in the next 20 years!

How do we avoid getting the national debt to $80 trillion, or to $200 trillion?

We come right back to what the Federal Reserve is doing right now. Which is keeping the explosion in the national debt from occurring, by keeping interest rates at very, very low levels, these low levels. Oh, they may issue press releases saying it's about economic growth - and that's a factor - but it isn't happening in isolation.

What the Federal Reserve and the federal government are doing, is the same thing they were doing the late 1940s and through the 1950s and 1960s, is keeping interest rates very low. Which keeps the national deficit from exploding.

However there is a very powerful effect on retirement investors, because the interest rate levels paid by the US government help determine interest rates in all categories for investors in the United States (and in other nations with their own national governments).

Part II

In the second half of this video (and transcript), which is available on my website, DanielAmerman.com, and is linked below, we take a look at the extraordinary impact on savers and retirement investors, why the world has changed in a way that most retirement planning still does not take into account, and how the sharp increase in the federal debt could change both your lifestyle and your security in retirement, possibly for decades to come. Continue To Part II

Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Website: http://danielamerman.com/

E-mail: mail@the-great-retirement-experiment.com

Daniel R. Amerman, Chartered Financial Analyst with MBA and BSBA degrees in finance, is a former investment banker who developed sophisticated new financial products for institutional investors (in the 1980s), and was the author of McGraw-Hill's lead reference book on mortgage derivatives in the mid-1990s. An outspoken critic of the conventional wisdom about long-term investing and retirement planning, Mr. Amerman has spent more than a decade creating a radically different set of individual investor solutions designed to prosper in an environment of economic turmoil, broken government promises, repressive government taxation and collapsing conventional retirement portfolios

© 2016 Copyright Dan Amerman - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: This article contains the ideas and opinions of the author. It is a conceptual exploration of financial and general economic principles. As with any financial discussion of the future, there cannot be any absolute certainty. What this article does not contain is specific investment, legal, tax or any other form of professional advice. If specific advice is needed, it should be sought from an appropriate professional. Any liability, responsibility or warranty for the results of the application of principles contained in the article, website, readings, videos, DVDs, books and related materials, either directly or indirectly, are expressly disclaimed by the author.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.