Four Stock Market Black Monday Takeaways Wall Street Hopes ETF Investors Never Understand

Stock-Markets / Exchange Traded Funds Sep 09, 2015 - 03:46 PM GMTBy: ...

MoneyMorning.com  Keith Fitz-Gerald writes: Exchange-traded funds – ETFs for short – are billed as among the most investor-friendly products ever created, thanks to low fees, intra-day pricing, and unprecedented flexibility versus the mutual funds they’ve ostensibly “replaced.”

Keith Fitz-Gerald writes: Exchange-traded funds – ETFs for short – are billed as among the most investor-friendly products ever created, thanks to low fees, intra-day pricing, and unprecedented flexibility versus the mutual funds they’ve ostensibly “replaced.”

In reality, ETFs are yet another Wall Street creation designed to separate you from your money.

Proponents will undoubtedly cry foul as will many Wall Street professionals when they read this. That’s understandable – they’ve got a lot to lose. According to Morningstar, there are more than 1,400 ETFs trading in U.S. markets, holding an estimated $3 trillion in assets. In 2005 that figure stood at $300 billion. In 1990 it stood at nothing.

We’re going to talk about why that’s the case today and, of course, four key takeaways every ETF investor should understand.

Don’t get me wrong – ETFs aren’t a landmine if you understand how to use them, as I’m about to show this month’s Money Map Report readers.

Chance, to paraphrase Louis Pasteur, favors the prepared mind…

…to which I’ll add “especially when it comes to profits.”

A Quick Bit of History Sets the Stage

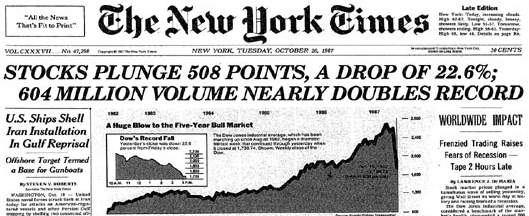

To understand why ETFs are such a rigged game, we have to go back to another Black Monday – October 19, 1987.

I recall it very clearly.

On the heels of what had been a banner summer and two rockin’ years leading into that fall, the markets were fueled by a combination of low interest rates, merger mania, and leveraged buyouts. Then, as now, debt was key and IPOs were hotter than hot. The character Gordon Gekko, played by Michael Douglas in the 1987 movie Wall Street, figured prominently in the social meme when he said: “Greed is good.”

At the same time, insider trading was rampant and the SEC was clamping down, despite being outmaneuvered at nearly every turn. Traders turned to hedging as a means of protecting against temporary downturns. This, too, should sound familiar.

To keep things from getting completely overheated – and you knew this was coming – the Fed stepped in to increase short-term interest rates. Predictably, all hell broke loose.

Keen to protect their positions, institutional managers scrambled and billions of dollars’ worth of sell orders hit on October 19 within minutes. I stood slack-jawed as the tape went by.

While the institutional damage was bad, the individual experience was worse.

Those holding mutual funds were particularly hard hit because they couldn’t sell until the markets had closed. By then the Dow had fallen 22.6% in a gut wrenching one-day drop that saw nearly $500 billion wiped from the slate.

Never mind that the markets recovered quickly. The damage had been done – there had to be a way to sell during market hours using investments covering a basket of securities.

Three years later, State Street Global Advisors launched the first U.S. ETF. Created to track the S&P 500, the Standard & Poors Depository Receipts ETF is now known as the SPDR, or “spider” for short. Other broad index-based alternatives sprung up in short order.

Today there are more than 1,400 ETFs covering everything from indices to very, very specialized investments, from the iPath Dow Jones-UBS Livestock Subindex Total Return (NYSEArca:COW) to the Market Vectors Gaming ETF (NYSEArca:BJK).

According to Wall Street, they’re vastly superior to mutual funds because they have higher daily liquidity, lower fees, and can be traded throughout the day.

If you’re starting to smell a rat, you’re not alone.

Understanding What an ETF Is and Isn’t

Mutual funds represent a basket of shares priced at the end of any given trading day. When you buy shares in one, you send your cash to the fund company which then, in turn, uses that money to purchase shares of the companies it intends to buy. Then the fund company issues additional fund shares.

ETFs are security certificates. That means ETFs are really two layers – shares that trade like stocks and the basket of securities they represent. Only authorized participants – read large institutional investors and broker dealers – actually buy or sell shares directly to or from the ETF using blocks of tens of thousands of shares called creation units. In other words, you’re an indirect owner.

Most of the time an ETF’s Net Asset Value (NAV) closely matches the underlying index basket of securities it tracks. But not always.

Here Comes the Curveball

If the underlying securities upon which an ETF is based stop trading, the ETF in question cannot be priced.

And how would that happen?

The NYSE put trading curbs in place known as “circuit breakers” following the 1987 meltdown intended to reduce volatility and prevent massive price panic, as well as to give traders time to digest whatever is driving the meltdown. Other exchanges have similar rules designed to slow down trading. Still more rules came and went following the 2010 Flash Crash.

Monday’s circuit breakers tripped a staggering 1,300 times and in such rapid fashion that broker dealers and ETF market makers were, in turn, unable to price the NAV of many popular ETFs holding the most popular stocks – Apple, Google, Netflix, Home Depot and more.

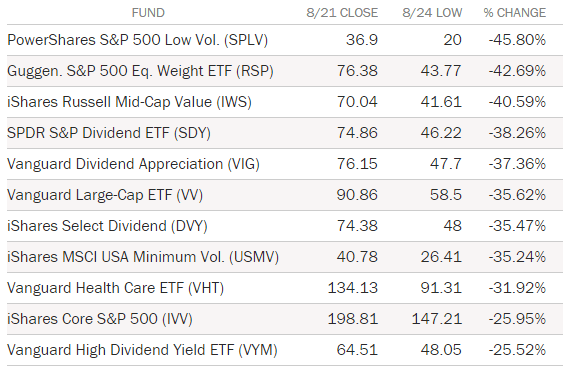

Consequently, one in four ETFs fell more than 20% because they couldn’t be priced.

Source: MaxFunds

Several big name funds long viewed as bastions of stability slid 25% – 46% even though their underlying assets fell only a fraction of that.

For example, the $2.5 billion Vanguard Consumer Staples Index ETF dropped 32% within minutes of opening, even though the underlying holdings only dropped 9% according to The Wall Street Journal and FactSet. It was halted six times in 37 minutes.

Faced with the prospect of getting run over and losing a lot of money, traders pulled pages directly from our playbook. They started using Lowball Orders to buy and price targets to sell as a means of controlling their risk. Protecting your money went right out the proverbial window.

In this case, traders saw that ETF shares were trading at huge discounts to some of the most popular companies. So they bought the ETF while simultaneously selling those same companies and locked in the difference as profits in a process known as arbitrage.

Academics argue that arbitrage is a necessary function for markets because it helps markets return to normal. That’s true when prices are dislocated based on external variables or exogenous events.

However, in this instance, it’s entirely conceivable that the largest traders and high speed traders, in particular, have an incentive to create their own arbitrage opportunity by artificially driving down the prices of individual securities and intentionally triggering the circuit breakers we’re talking about. In effect, they’re making their own profits at the expense of yours.

It’s hardly surprising that Virtu, Volant, and other high-frequency traders had their most profitable days since the Flash Crash of 2010. BATS Global Markets, one of the big three U.S. stock exchange operators, reported a record 1.3 billion orders processed… every one of them a revenue producer.

Mohit Bajaj, director of ETF trading solutions at WallachBeth Capital, LLC, put it succinctly: “ETFs were essentially another victim.”

I agree.

Yet, all is not lost – if you understand these four rules.

- ETFs are not stock replacements, so don’t trade them that way. Doing so only plays into the hands of market makers who want you to panic and who are ready, willing and able to profit when you do.

- ETFs are an allocation instrument created for Wall Street’s benefit. Don’t make the mistake of thinking about ETFs the way you think about individual companies. They are blunt instruments for tracking broad brush moves, not the laser like scalpels Wall Street would have you believe.

- Never use market orders for ETFs. Doing so only feeds high speed traders and arbitrageurs at your expense. Limit orders are the way to go, especially when it comes to trailing stops.

- You’re better off with mutual funds, especially when it comes to core investments. One of my favorites is the Vanguard Wellington Fund (VWELX), which has turned in plenty of double-digit returns since 1929 when it was created.

In closing, I wish I could tell you that there won’t be another Black Monday. But I can’t.

Until regulators decide to protect investors instead of Wall Street, this kind of nonsense is going to continue.

So recognize the game for what it is and don’t, under any circumstances, make it easy for Wall Street to win.

I’ll show you how.

Until next time,

Keith

Money Morning/The Money Map Report

©2015 Monument Street Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Protected by copyright laws of the United States and international treaties. Any reproduction, copying, or redistribution (electronic or otherwise, including on the world wide web), of content from this website, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of Monument Street Publishing. 105 West Monument Street, Baltimore MD 21201, Email: customerservice@moneymorning.com

Disclaimer: Nothing published by Money Morning should be considered personalized investment advice. Although our employees may answer your general customer service questions, they are not licensed under securities laws to address your particular investment situation. No communication by our employees to you should be deemed as personalized investent advice. We expressly forbid our writers from having a financial interest in any security recommended to our readers. All of our employees and agents must wait 24 hours after on-line publication, or after the mailing of printed-only publication prior to following an initial recommendation. Any investments recommended by Money Morning should be made only after consulting with your investment advisor and only after reviewing the prospectus or financial statements of the company.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.