When Pro Players Fritter Away Millions

Personal_Finance / Pensions & Retirement Feb 05, 2015 - 06:49 PM GMTBy: Dennis_Miller

By Dennis Miller

By Dennis Miller

How is it possible for one man to burn through $400 million and wind up filing for bankruptcy, $27 million in the hole? Boxer Mike Tyson made it happen, and he’s in good company among professional athletes. Yet other professional athletes parlay their sizable earnings into nest eggs that grow and last.

Why the two divergent paths?

Today I’m speaking with Hank Sargent, who works at one of the top player agencies in the country to answer that very question.

First, a bit of background is in order. Hank was my son’s roommate and teammate on a college national championship baseball team. While he never played professionally, he’s been involved in professional baseball for over 25 years. He’s also the only person I know with a World Series ring from an NCAA championship team and a major league baseball championship team.

Now, let’s jump to it.

Dennis Miller: Hank, will you share a little about your background?

Hank Sargent: As you know I had a wonderful experience during my collegiate career at Florida Southern College. Knowing my playing days were numbered, I focused my energies toward coaching. Upon graduation I was fortunate to secure the Head Assistant position at my alma mater.

At that time, the program was really flourishing and numerous players were entering professional baseball. A lot of scout traffic came through our program. Ultimately, that led me to a 15-year scouting career with the Montreal Expos, Cincinnati, and Anaheim at various levels—from area scout to cross-checker and finally associate scouting director.

In 2004 I was offered an opportunity to move into a different sector of the industry; I partnered with a close friend and now serve as a baseball agent. We have a wide range of clients, including many household names and some that will soon be in the Hall of Fame.

Basically, I’m a life coach for professional baseball players, helping them navigate the journey from amateur to big leaguer.

Dennis: For most people, their peak earning years are during their 50s and 60s, when they’re more mature and understand the pressing need to save. The opposite is mostly true for your clients; their peak earning years are often in their 20s.

I know you work closely with your clients to help them translate early financial success into a lifetime portfolio. How do you convince these young folks to save, invest, and not spend it all?

Hank: First and foremost, a professional athlete typically has a small window of high earnings. Encouraging safe and conservative investments is our approach. We treat athletes almost as if they were elderly because their assets need to last.

With the new agreements in place there is a limit on signing bonuses for top draft picks. A first-round pick, in round numbers, could receive a $3 million contract. Our first challenge is to help them understand that they did not win the lottery. No matter how good they may be, there are no guarantees they will make the major leagues or sign a huge free-agent contract. As a Cub fan, I know you are familiar with Mark Prior, a pitcher that was picked number 2 in the draft. He had huge potential; however, injuries cut short his career and his earnings were a small fraction of what they could have been.

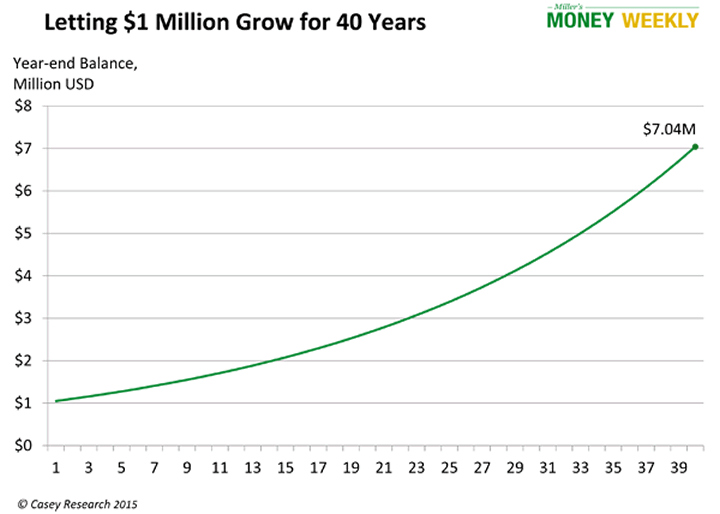

One thing I try to impress upon them is the value of compound interest. It makes a huge difference if they begin saving immediately. If a player signs at age 20 and invests $1 million of his signing bonus, at a compound interest rate of 5%, it will be worth over $7 million when he’s 60. Many say their goal is to be set for life, and part of our job is to show them how to do it.

Throughout a player’s career, we encourage them to budget for a special purpose and then stash the rest away. They have to realize that their peak earning years happen when they’re young, and in less than a decade they may be over; they must start saving immediately.

Dennis: You have clients from all walks of life. Many of the Dominican players sign their first contract at a very young age and have little formal education. I think Sammy Sosa was a 14-year-old shoeshine boy when he signed his first contract, and he made well over $100 million in his career. Then there are college players that are better educated.

One of my son’s high school teammates was an Academic All-American in college football and earned a degree in finance. He played for 14 years in the NFL and has two Super Bowl rings. I know he immediately invested his original signing bonus and has done quite well.

While helping a client build financial security is always your goal, each situation must vary. The pressure from family and friends on these kids with newfound wealth must be tremendous. What are some of the different approaches you use to help the entire spectrum?

Hank: You are absolutely correct. Most people don’t understand how a player agency works. Until the player signs their first major league contract, the agency receives no compensation. We may work for a client for several years while they are in the minor leagues, with no compensation.

We’re very specific with our target recruits. We are regionalized geographically and have strict criteria for the caliber of baseball player we look for. Our focus is typically on the top two to three rounds of the draft each year. We typically stay in the southeast region of the country, and we always directly involve the parents of our recruits.

Understanding an athlete’s family dynamics is critical because it affects your ability to be a good advisor. Each player will be in a different station of life at key junctures of his career. “High school bonus babies” are still connected to their parents. College players may be more independent or have a significant other in the mix. The bottom line is, being familiar with each client’s family dynamic helps us plan a more specific strategy for protecting his assets.

Dennis: You mention involving the entire family. I believe a lot of basic beliefs are set before a young person enters high school. Chicago sportswriters used to joke about Kyle Orton when he was the Bears’ quarterback. They said the team parking lot was fully of fancy cars— Range Rovers, BMWs, Hummers, you name it. In the last parking spot was a Toyota Prius that belonged to the quarterback. His choice of automobiles said something about his values and priorities.

How do you guide clients who may not have had much mentoring at home?

Hank: As a boutique agency we can limit the number of clients and truly get to know them. As for mentoring, it starts with simple direction: stay humble; stay true to who you are; stay within your means; stay within your present contract; and stay on a budget.

This sounds extremely elementary, but at the end of the day, athletes are creatures of habit. They like simple and direct. Most high school signees and many collegiate players have never balanced their checkbook or paid a credit card bill. Starting with simple budgets and life skills can really help. Quite honestly, lots of this is simply parenting.

Dennis: One final question. For every $100 million ballplayer there are a dozen who make a fraction of that. Are there major differences you can spot between those who hold on to their money and those who don’t?

Hank: For me, it starts and stops with three easily recognizable elements. Upbringing is by far the most important. The core values of a player will determine his direction and success in handling money.

Common sense is a close second. Athletes typically get hit from all sides once they’ve accumulated some wealth and stardom. The ability to make sensible decisions and to be secure in those choices has tremendous value in protecting your assets.

The third element combines intellect and integrity. Making good decisions typically requires having all of the information, but the ability to decipher the information correctly is the real key. And to bring this full circle, integrity allows the athlete to stay true to himself and his professional goals.

Dennis: Hank, thank you for your time. I have one final thought… Though a 35 year-old closing out his baseball career isn’t your traditional retiree, the Miller’s Money team has developed a nifty tool that your players might find helpful. We named it the Retirement Income Calculator, but you can use it at any age to project how long your portfolio will last. It’s easy to adjust to your personal circumstances, whether you plan to retire at age 35, 65, or 95. Readers can access a complimentary version here.

Hank: Thanks, Dennis. This was fun, and I’ll pass that along.

Casey Research Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.