Bush Economic and Housing Boom was Fueled by Credit Expansion

Economics / US Economy May 26, 2008 - 10:51 AM GMTBy: Gerard_Jackson

America's sluggish economy has the ever-so patriotic Democrats and their media playmates drooling over the prospect of a recession and rising unemployment. Those political activists who have the brazen effrontery to call themselves journalists have been gleefully drawing unfavourable comparisons between the economy under Bush and the Clinton boom, painting the former as a dreadful record of lousy growth, stagnant wages and tax cuts for the rich.

America's sluggish economy has the ever-so patriotic Democrats and their media playmates drooling over the prospect of a recession and rising unemployment. Those political activists who have the brazen effrontery to call themselves journalists have been gleefully drawing unfavourable comparisons between the economy under Bush and the Clinton boom, painting the former as a dreadful record of lousy growth, stagnant wages and tax cuts for the rich.

Honest journalists — of which there are very few — recognise that the economy has gone through a boom under the current administration. Nevertheless, some of them feel that things are not quite right. What they fail to note is that things are never quite right in a boom. It's the nature of the beast and something that they fail dismally to understand.

Robert Shiller has been making noises about the housing market and sub-prime lending, which has turned some minds to Shiller's book Irrational Exuberance . This work caused something of a controversy in popular economic circles, particularly in the financial press. Shiller correctly points out that the Dow Jones Index more than tripled in five years, leaping from 3,600 in 1994 to over 11,000 by 1999. Unprecedented and, in his opinion, unsustainable.

Examining the sustainability side he noted that during this great leap in the Dow the nation's GDP rose by less than 30 per cent, of which about 50 per cent is accounted for by inflation. Therefore the real increase in GDP was only about 15 per cent. Although corporate profits rose by nearly 60 per cent, this picture was not particularly bright when we consider that profits came from a recessed base. Looked at historically, profits were not high. Moreover, from an economic perspective were very few real profits anyway. This view is supported by Shiller's observation that the rise in the Dow "is not matched by real earnings growth".

He drew attention to the 1920s bull market which came to an end with the 1929 crash. (In fact, it was terminated in December 1928 when the Fed froze the money supply). Coming to price earnings ratios we find that for 2000 they averaged 45 times earning while they were 35 times earnings for 1929. That earnings ratios are completely out of kilter are not only obvious but a clear danger signal. But this always happens in these circumstances. He also refers to 1901 and 1966 as other major peaks in the market.

But pointing to major peaks in market activity tells us nothing about causes. Let us begin with the 1901 peak, which had its origins in the 1890s. Great amounts of gold began to flow into America in 1896 leading to a considerable expansion of bank credit and this fuelled a boom and triggered a stock market take-off. Now the increase in massive amounts of credit also sparked a merger mania, just as it did from 1924-1929, that largely occurred in the years 1899-1902. This is also the period that saw the market peak in 1901. In 1903 the economy had gone into a depression. It was no coincidence.

The end of the First World War witnessed a contraction in the American economy which was quickly reversed by rapid monetary growth that brought about the 1919-20 boom. The Fed applied the monetary breaks causing the 1920-21 financial crisis which became the sharpest contraction in American history. The recovery gave America the 1920s boom and the infamous 1929 crash. The 1966 market peak followed the same pattern. Rapid credit expansion fuelled the boom in stocks while a monetary tightening caused them to drop.

It is no great insight to point out that earnings ratios plummeted once these markets crashed, even dropping to zero during the great depression. This is what happens during depressions. The trick is explaining the forces at work and not to confuse symptoms with causes.

Each of these boom periods was preceded by rapid credit expansion. Each crash was preceded by monetary tightening. Looked at in this light the so-called business cycle becomes a monetary roller-coaster. That Greenspan raised interest rates by nearly two per centage points between June 1999 and May 2000 should have been seen as a red alert, as it was clearly an attempt to rein in credit.

Unfortunately Shiller is wedded to the fallacy that consumption drives the economy because it is about 66 per cent of GDP. The trouble here is that GDP ignores spending between stages of production. Once this spending is taken into the situation is reversed. Focussing on consumption led him into the error of thinking that the sub-prime debacle will slash house values and thus reduce consumer spending and hasten a recession.

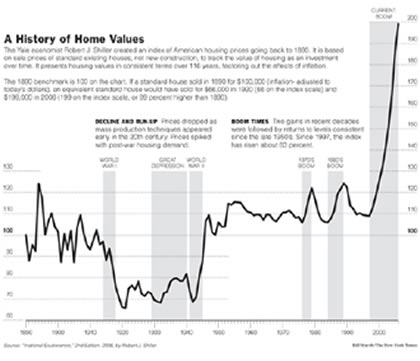

But values — including those in real estate — are not purchasing power. It is production and production alone that creates purchasing power. Therefore, if real estate values did dive this in itself would cause "aggregate demand" to contract. Ironically, the following chart, which comes from the second edition of Irrational Exuberance , makes my point.

In his book Shiller rightly points out that the decline in house price up to 1920 was the result of increased productivity in the building trade. Yet, since WWII house prices have continually trended upward despite increasing productivity. So why did prices more than counter the downward pressure on prices that rising productivity generated? The answer is Keynesianism. Booms are fuelled by credit expansion, otherwise known as "easy money" policies. By continually expanding credit the Fed has inexorably driven up house prices. And this is exactly what Shiller's chart shows.

As a postscript I should point out that the preceding view is largely in keeping with the monetarists' explanation of booms and busts. And yet there are fundamental and irreconcilable differences between the monetarists and the Austrians. The latter examines and stresses the microeconomic consequences of credit expansion, explaining why so-called price levels are not measures of inflation and how, even where the price level is 'stable', a depression can still come about.

By Gerard Jackson

BrookesNews.Com

Gerard Jackson is Brookes' economics editor.

Copyright © 2008 Gerard Jackson

Gerard Jackson Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.