The Busted Myth Of War And Economic Growth

Economics / Economic Theory Jun 15, 2014 - 03:45 PM GMTBy: Raul_I_Meijer

A strange point of view is expressed in George Mason University economics professor Tyler Cowen’s NY Times article ‘The Lack of Major Wars May Be Hurting Economic Growth’, strange in more ways than just the obvious ones. Of course we find it counterintuitive to link growth to warfare. And of course we don’t like to make a link like that. But there’s a lot more here than meets the eye. For one thing, the age-old truth that correlation does not imply causality, something Cowen hardly seems to consider at all. Which is curious, and certainly makes his arguments carry a whole lot less weight, and interest. It makes his whole article just about entirely one-dimensional.

A strange point of view is expressed in George Mason University economics professor Tyler Cowen’s NY Times article ‘The Lack of Major Wars May Be Hurting Economic Growth’, strange in more ways than just the obvious ones. Of course we find it counterintuitive to link growth to warfare. And of course we don’t like to make a link like that. But there’s a lot more here than meets the eye. For one thing, the age-old truth that correlation does not imply causality, something Cowen hardly seems to consider at all. Which is curious, and certainly makes his arguments carry a whole lot less weight, and interest. It makes his whole article just about entirely one-dimensional.

Here’s an excerpt:

The Lack of Major Wars May Be Hurting Economic Growth

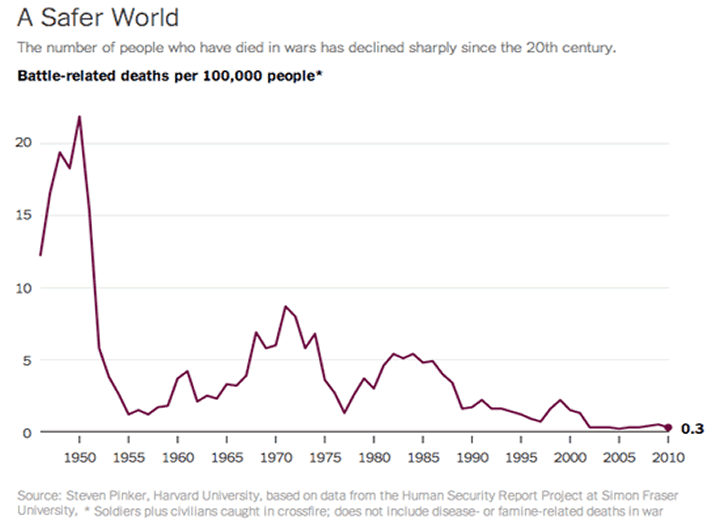

The continuing slowness of economic growth in high-income economies has prompted soul-searching among economists. They have looked to weak demand, rising inequality, Chinese competition, over-regulation, inadequate infrastructure and an exhaustion of new technological ideas as possible culprits. An additional explanation of slow growth is now receiving attention, however. It is the persistence and expectation of peace. The world just hasn’t had that much warfare lately, at least not by historical standards. Some of the recent headlines about Iraq or South Sudan make our world sound like a very bloody place, but today’s casualties pale in light of the tens of millions of people killed in the two world wars in the first half of the 20th century. Even the Vietnam War had many more deaths than any recent war involving an affluent country.

Cowen misses an elephant-sized potential culprit of the continuing slowness of economic growth: debt, in particular the exponentially fast growing debt levels that the – western – has seen since the 1970s. And which have grown to such proportions today that not including them in a list of possible causes is even suspicious.

Counterintuitive though it may sound, the greater peacefulness of the world may make the attainment of higher rates of economic growth less urgent and thus less likely. This view does not claim that fighting wars improves economies, as of course the actual conflict brings death and destruction. The claim is also distinct from the Keynesian argument that preparing for war lifts government spending and puts people to work. Rather, the very possibility of war focuses the attention of governments on getting some basic decisions right – whether investing in science or simply liberalizing the economy. Such focus ends up improving a nation’s longer-run prospects.

A curious argument is made here: a government’s focus on liberalizing an economy would bring more growth. While one might even be inclined to believe that in the present, as IMF-induced ideas of reform and liberalization are all the fad, what proof is there of it in historical records? For instance, did Germany, Japan, Russia and the US actually liberalize their economies in the late 1930s?

Tyler Durden has a respectable response to Tyler Cowen’s piece:

New York Times Says “Lack Of Major Wars May Be Hurting Economic Growth”

The fun part will be when economists finally do get their suddenly much desired war (just as they did with World War II, and World War I before it, the catalyst for the creation of the Fed of course), just as they got their much demanded trillions in monetary stimulus. Recall that according to Krugman the Fed has failed to stimulate the economy because it simply wasn’t enough: apparently having the Fed hold 35% of all 10 Year equivalents, injecting nearly $3 trillion in reserves into the stock market, and creating a credit bubble that makes the 2007 debt bubble pale by comparison was not enough. One needs moar! And so it will be with war. Because the first war will be blamed for having been too small – it is time for a bigger war. Then an even bigger war. And so on, until the most worthless human beings in existence – economists of course – get their armageddon, resulting in the death of billions.

Perhaps only then will the much desired GDP explosion finally arrive? Luckily for Cowen, he stops from advocating war as the ultimate panacea to a slow growth (at least for now: once the US enters a recession with another quarter of negative growth, one can only imagine what lunacy Krugman columns will carry). Instead he frames it as an issue of trade offs: “We can prefer higher rates of economic growth and progress, even while recognizing that recent G.D.P. figures do not adequately measure all of the gains we have been enjoying. In addition to more peace, we also have a cleaner environment (along most but not all dimensions), more leisure time and a higher degree of social tolerance for minorities and formerly persecuted groups. Our more peaceful and — yes — more slacker-oriented world is in fact better than our economic measures acknowledge.”

But Durden doesn’t bring up, let alone address, the debt situation either. Let’s go to the graph Cowen posted with his article, and then talk correlation and causality:

So yes, there were fewer battle related deaths. And over the past years, we’ve seen less economic growth. But how and why does that mean one leads to another? One more thing, before we continue, about debt: without having the ‘made for the hockey stick model’ exponential rise in debt levels basically ever since Nixon dumped Bretton Woods – or gold – in 1971, it should be awfully obviously clear to everyone that we would have much less economic growth, at least as far as it’s expressed in GDP numbers and the like. We have borrowed much of our growth since the 1970s, we just didn’t realize it at first, and many still don’t.

John Haskell in the Bangor Daily News has another reaction to Cowen in ‘War and Economic Growth’ , in which he claims, quoting Ezra Klein, that the reason government R&D spending is inefficient is that it’s tied up in military projects – I think his ‘defense’ is a very manipulative and misleading term to use in this context -. Still what neither do address is why that is. Though, granted, they do suggest that while it may be economically inefficient, it is ‘politically efficient’.

And yes, there is some possible link between that and my own idea that R&D spending is tied up in defense projects, because 1) that’s where it was in times the US did indeed go to war, and the idea stuck, because 2) this situation solidified the position of the military industrial complex, which knows just what politicians to target with which lobbyists. In fact, since Eisenhower warned the American people about it, it’s grown enormously and should today really be labeled the financial military political industrial complex. At least it now it truly deserves the moniker ‘complex’.

However that may be, Cowen’s is overall still a strange argument. Because a ‘lack of war’ is not the only thing that changed since the ‘glory days’ of economic growth. Ever since the ‘battle related deaths’ peak in the graph, which occurred in 1950, and the later and smaller peak in 1970, not only did debt rise exponentially, so did for instance the world population, which went from 2.5 billion in 1950 to almost double 3.7 billion in 1970 to almost double again 7.1 billion today. And while undoubtedly some part of that can be explained by a ‘lack of warfare’, then again, a probably much bigger part of it is due to better medicine, falling child death rates and longer life expectancies. I’m not claiming this leads to lower economic growth, that’s Cowen’s hobby horse, I’m just saying that fewer war casualties is just one stat that changed since WWII, and I find it far-fetched – I’m being polite here – to pick out one stat from a very long list and hammer it till you’re tired. Because he does that, and ignores so much else, Cowen and his argument have very little credibility.

And I can go on. Another thing that changed since 1950 is that people, certainly in the west, got a whole lot richer. Since about 1980 more and more of that was borrowed, but the feeling remained. And still does, because people are simply not told that they have become much poorer. And as long as the feeling persists, we might want to consider that maybe we have arrived at such a thing as enough economic growth after all. That maybe economic growth is just so yesterday, and peace is the new black.

Maybe the concept of economic growth belongs only in outdated economics textbooks, from whence spouts the notion that growth equals happiness, and therefore if war is the only way to achieve – strong – growth, we can be happy only when we wage war. Maybe people don’t want all that economic growth al that much, maybe they have a notion deep inside that they’re satisfied, that they have enough gadgets and frills, and they just want their kids to grow up to be happy, and absolutely not send them to war. And you can call that a ‘slacker’ attitude if you will – again a manipulative choice of words -, but that’s perhaps nothing but yet another misleading term.

There is no rational ground on which to believe that there is no possibility of people reaching a point of satiation when it comes to growth. The biggest problem there is seems more likely to be the system in which we live, which is still based on notions that no longer hold, on economics textbooks that are based solely on political preferences (economics is nothing but politics in disguise), and on groups that have held on to power, and expanded it, for 100 years or more, and whose grip on power depends on their ignorant foot soldiers believing in growth. Those groups may win the day and lead us into more and, given the “improvements” in weapons systems, more extreme warfare. But that doesn’t in any way lend credence to Tyler Cowen’s ‘war and growth’ ideas, especially when he refuses to acknowledge other growth correlations such as debt and population numbers, and thereby fails to establish any causality. This myth is busted.

By Raul Ilargi Meijer

Website: http://theautomaticearth.com (provides unique analysis of economics, finance, politics and social dynamics in the context of Complexity Theory)

Raul Ilargi Meijer Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.