The Mysterious Case of the Commodity Conundrum, Securitization of Commodities and Systemic Concerns (Part 2)

Commodities / Derivatives Apr 23, 2008 - 03:16 AM GMTBy: Mack_Frankfurter

Part 1

"The theories which I have expressed there, and which appear to you to be so chimerical, are really extremely practical—so practical that I depend upon them for my bread and cheese." — Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Scarlet (1888)

"The theories which I have expressed there, and which appear to you to be so chimerical, are really extremely practical—so practical that I depend upon them for my bread and cheese." — Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Scarlet (1888)

The mysterious case of the commodity conundrum is sure to elicit passionate debate on either side of the equation—is the commodity boom due to speculation or fundamentals? By the time you read this, a battle in this dispute will have taken place on April 22, 2008 with the CFTC roundtable on agricultural markets.

Academic Mountebanks

Modern finance, or “market fundamentalism” as George Soros calls it, is based on a little known assumption called “rational expectations equilibrium,” from which financial models are derived.

Admittedly, models are only an abstraction from reality. Expecting such models to be exactly right is unreasonable, and it is generally understood that neoclassical economic models have inherent limitations. Such systems are based on perfect competition, assume that the economy is stable, and that markets naturally return to equilibrium after a disturbance.

Hence, such models maximize utility and/or profits in a world of constraints based on the choices of “rational” economic agents. By definition then, these models relegate speculators to the role of that very agent which maintains equilibrium. Hence, markets are “informationally efficient.”

Paradoxically, if historical market data is assumed to represent equilibrium and “the future is merely the statistical reflection of the past,” then one could inversely argue that perfect competition minimizes these models' usefulness as a mechanism from which to make speculative decisions.

In other words, rational expectations compel such models to simply validate that market price data is equated to equilibrium; unless the opposite is true—that markets are in fact imperfect and rational expectations is untenable, which in turn undermines the veracity of these models.

This is where post-Keynesian ideas, including the theory of reflexivity and behavioral finance, originate. Such view takes the stance that markets are complex, messy and uncertain, and exhibit behavioral tendencies related to the “wisdom of crowds” and “madness of crowds.” Further, economic fundamentals and market prices create a feedback loop, each influencing the other.

Philosophically, the “rational expectationalists” believe the economy naturally reverts to equilibrium, and seek “beta” in the wisdom of crowds ; while the “reflexive behavioralists” believe that the world is in a state of constant disequilibrium, and seek “alpha” opportunities in the madness of crowds .

This may be an oversimplification, but it sets the framework for the discussion that follows…

As noted in a June 2006 Senate Subcommittee on Investigations Staff Report, titled The Role of Market Speculation in Rising Oil and Gas Prices: A Need to Put the Cop Back on the Beat , “Recent academic research indicating that commodity futures have performed as well as stocks and better than bonds, with less risk, also has boosted expenditures on energy commodity futures.”

Setting such academic studies aside, the buried truth is that the academic legacy of empirical tests using a variety of asset pricing models, including the CAPM, hedging-pressure hypothesis, or arbitrage pricing theory, have produced inconsistent results as to whether there is, in fact, positive expected returns from speculating in the futures market. This legacy goes back to Keynes.

So what changed in the prevailing wisdom of academics? The current mantra is that there are three, sometimes four, sources of return that come from “investment” in commodities.

First, there is the “collateral yield” which references the fixed income yield that emanates from the “de minimis” good faith deposit required to trade derivatives. Second, is the “spot return,” which relates to the change in pricing of the underlying commodity—a straight forward concept. Third, is something called the “roll yield or return” which according to hardassetsinvestor.com is “ a bit more complicated to understand, but it is absolutely critical to your returns .” And occasionally there is reference to a fourth source, a “strategy return,” relating to “how one weights and rebalances the components of a commodity index.”

Our working paper takes issue with the concept of the roll yield. To begin with, the roll yield is derived from a water-down definition of backwardation and contango, which is based on, what Hilary Till in her book “Intelligent Commodity Investing” describes as, the “term structure of the futures price curve.” We are not alone; Erb and Harvey (2006) also debated this notion.

This current convention then became fodder for the fantasies of various papers including a much cited Yale University paper on commodity futures by Gorton and Rouwenhorst (2004), proponents of the roll yield. And because this paper is briefly mentioned by Jim Rogers in his book “Hot Commodities,” a perpetuated myth evolved around this deficient theory into the investor mindset.

Now, if one takes a close look at the study which underlies Gorton and Rouwenhorst's conclusion, it becomes obvious that the model they use supports a fictional trade that cannot be duplicated in real life. Rather than rolling the futures contract forward, they roll the futures contract backward to “prove” their thesis. This is facilitated with the idea that the expected future spot price is a pre-determined static constant, when in fact the “expected future spot price,” which is the lynchpin to Keynes' theory of normal backwardation, is an unknown, to be discovered, in the future, at the time that the futures contract converges with the spot price. This is best illustrated through examples.

Futures contracts unlike securities are instruments with a finite life, and terminate on pre-specified dates when the futures contract converges with the spot price. At that point delivery of the underlying cash commodity is made between commercial participants. A wheat futures contract, for example, has delivery contracts for March, May, July, September and December. As a matter of practice, most speculators do not allow their positions to enter the delivery period, and a perpetual long futures position will require a trader to “roll” the contract from one contract month to the next.

As a the real world example, let's say that a trader goes long a March futures contract at $100, subsequently rolls that contract into a July futures contract 60 days later by liquidating the March contract at $120, and then reentering the long position via a July futures contract at $121, whereupon sixty days later exists the position altogether and liquidates the July contract at $111.

The long March futures contract trade results in a $20 realized gain and the long July futures contract trade results in a $10 realized loss. Very simply, the net gain of $10 is then divided into the original investment amount of $100 for a 10% return. This is straightforward and logical.

On the other hand, the model for calculating the roll yield or roll return is not possible in the real world, but seeks to prove something on the basis of a fictional trade.

Again, let's say that a trader goes long a March futures contract at $100, and 60 days later liquidates the March contract at $120. The academics referred to this as the “spot return” and the net gain of $20 is then divided into the original investment of $100 for a 20% return.

At the same time the trader purchased the March futures contract, let us assume that the July futures contract was trading at $90. The roll return model then subtracts this $90 July futures contract price in the past from the current $120 March contract liquidation price (not possible in the real world). The academics call this the “excess return” and the net gain of $30 is then divided into the $90 July contract price (why not the $100 denominator?) for a 33% return.

As a result, the “arithmetic” roll return is equal to 33% minus 20%, that is13%... Huh?

It is clear that the model aims to statistically identify an approximation of excess returns from historical price data, but even Till (2007) states that roll returns “related to the term structure of each futures contract [is] meaningfully so only at long investment horizons.” Till also states “the convention of separating out futures-only return into spot return and roll return is solely for performance-attribution purposes.”

In fact, there is an inherent flaw in the roll return model. Accordingly, and as a direct challenge to other researchers who posit the existence of the roll return purported from empirical tests, we argue that such excess returns are actually leveraged returns as a function of the model itself!

Furthermore, if one is familiar with the Black-Scholes option pricing model, in essence roll yield proponents are using a similar paradigm, without acknowledging that that the expected future spot price is not a static constant (i.e., strike price), but rather an unknown, to be discovered, in the future, at the time that the futures contract converges with the spot price.

Hypothetically, the term structure of the futures price curve may indicate backwardation and contango, but classical commodity pricing theory relates these concepts to the relationship between a specific futures contract price and that specific contract's “expected spot futures price.”

Expanding on Kaldor's (1939) ideas about “supply-of-storage,” Working (1948) observed that since storage costs are normally higher the longer a commodity is stored, the futures price at increasingly distant delivery dates will ordinarily be higher than at earlier dates, and that the difference will be the cost of storage. As a consequence, the natural slope of the term structure of the futures price curve indicates contango, such that the spot price is below subsequent futures prices.

So how can it be that Keynes (1930) idea of “normal backwardation” is assumed to be the so-called prevalent constitution of the commodity futures market? Classical theory propositions that backwardation, which occurs when the futures contract is priced lower than the spot price, is a result of “congenital weakness” and of “convenience yield,” an indicator of scarcity.

In combination, storage cost (which includes costs such financing, insurance, transportation, etc.) and convenience yield is expressed as the cost-of-carry which is derived from Kaldor's (1939) equation: futures price minus spot price equals storage costs minus convenience yield. Conversely: convenience yield equals spot price minus futures price plus storage costs. As a result, the expected spot futures price should theoretically equal the current spot price plus the cost-of-carry.

The funny thing is that this creates a problem with circular logic. The conundrum is called “causal relativity.” In order to calculate the model, one needs a constant as a reference, but the proposed constants—the futures price and the spot price—are actually variables, continually changing as a function of the price discovery process within the commodity markets.

The problem is made complicated for outright speculators because they cannot on a macro level truly know whether storage costs or convenience yield has increased or decreased due to a change in fundamentals, or whether an arbitrage opportunity exists because of anomaly in the cost-of-carry.

In other words, while the arbitrage model does eventually force convergence of the futures and spot prices upon settlement, the reflexivity of these relationships before settlement can also skew market direction in one way or another based on the participant's behavior.

Classical commodity theory provides different variations on the formula used to calculate the futures, spot and convenience yield relationships. Our working paper, in order to better frame the circular logic conundrum suggests the use of an error term such that the formula looks like this:

F t = S 0 ( o ± y ± ε ) t , where F t is the futures price, S 0 is the spot price, o is the storage outlay, ± y is the convenience yield or inconvenience yield (a term we introduced in our working paper), and where ± ε is a random error term with y determinable as a separately calculated variable; or

F t = S 0 ( o – y · ε ) t , where ε is a random error factor from which ± y can be inferred, but is only determinable as a function of whether ε is either ≥1, or ≤1, or whether ε equals 0, in which case the cost-of-carry consists of storage outlay only without any convenience yield attribute.

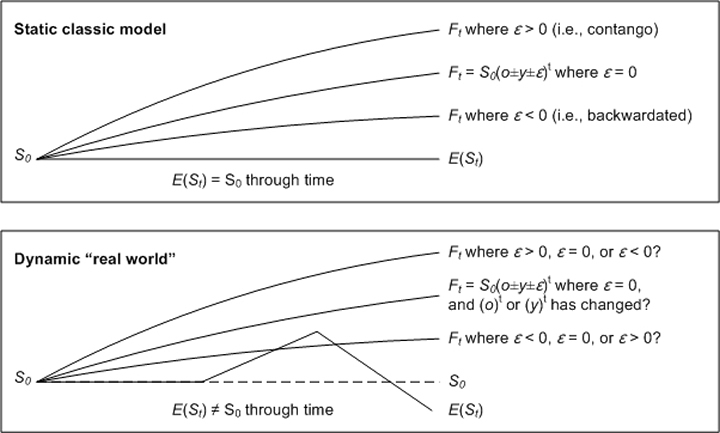

A picture is worth a thousand words and so we provide the following diagram to reveal the reflexive interaction and complexity of these concepts. (Note: for simplification the graphic below uses the first formula above, where E ( S t ) equals the expected spot future price.)

The diagram illustrates how it is possible to have a positive sloping term structure of the futures price curve, which is usually referred to as contango market conditions, resolved to Working's (1948) empirical observations about the relationship between futures prices and storage costs, while at the same time also exhibit either backwardated or contango market conditions.

The central problem with forward pricing, as this analysis reveals, is that it is difficult for any individual speculator, much less a crowd of speculators, to authoritatively state that the markets are backwardated or contango. Specifically, the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorem raises the specter that generalized assumptions about the cost-of-carry may be inconsistent with the intrinsic operating context and micro-economic assumptions of an individual bona fide hedger.

In other words, ExxonMobil, because it is a bona fide hedger, is able to determine whether the futures market is contango relative to its known storage costs and customer requirements; likewise, Chevron-Texaco, which may have the same or different economic assumptions, can be backwardated because the convenience yield it provides to its customers may require it to “carry stocks beyond known immediate needs and take [its] return in general customer satisfaction.”

The ironic twist is that the Wall Street paradigm of multiple betas has ported the alpha decision to the investors. If there is a persistent source of return at this stage in the commodity bull, it is likely now being paid by consumers (society) in the form of inflation. For this, the U.S. Treasury is not without blame.

But what if it is a zero-sum game? How do you know if/when you are not the greater fool? Wall Street has a bad habit of taking retail for the sucker. Come to think of it, these ideas are not mutually exclusive.

Our research indicates that commodity pricing models have inherent shortcomings in being able to pinpoint a definitive source of structural risk premium within the complexity of the real world global macro economy. Further, commodity pricing is observable materialization of behavioral finance, where risk, return, leverage and skill operate un-tethered from the anchor of beta , such as that which may be assumed by investors when “investing” in a commodity-linked ETF.

We hypothesize that the classic “arbitrage pricing theory” contains circular logic, and as a consequence, its natural state is disequilibrium, not equilibrium. We extend this hypothesis to suggest that the term structure of the futures price curve, while indicative of a potential roll return benefit or detriment, in fact implies a complex series of “roll yield permutations” as described by our working paper.

Similarly, the “hedging response function” elicits a behavioral risk management mechanism, and therefore, corroborates social reflexivity. All of these models are inter-related, and each reflects certain qualities and dynamics within the overall futures market paradigm.

In the final analysis, perhaps this commodity bull market may simply be a real world incarnation of the Thomas theorem: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

“Life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind of man could invent.”

End of part two of a three part series. To be continued...

By Mack Frankfurter

http://www.cervinocapital.com

Every effort has been made to ensure that the contents have been compiled or derived from sources believed reliable and contain information and opinions, which are accurate and complete. There is no guarantee that the forecasts made, if any, will come to pass. This material does not constitute investment advice and is not intended as an endorsement of any specific investment. This material does not constitute a solicitation to invest in any program offered by Managed Account Research, Inc. or any commodity trading advisor mentioned in the article, including any program of Cervino Capital Management LLC which may only be made upon receipt of its Disclosure Document. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Investment involves risk. Investing in foreign markets involves currency and political risks. The risk of loss in trading commodities can be substantial.

Author's Background:

Michael "Mack" Frankfurter is a co-founder and Managing Director of Operations for Cervino Capital Management LLC, a commodity trading advisor and registered investment adviser trading from Los Angeles , California . Mr. Frankfurter is also the Chief Investment Strategist and an Associated Person of Managed Account Research, Inc., an independent Introducing Broker focused on advising its clients in managed futures investments. In addition, he is a Managing Partner of NextStep Strategies, LLC which provides consulting services to companies in the financial industry. Occasionally, he pens articles as a freelance financial writer.

Copyright © 2006-2008 Michael “Mack” Frankfurter, Author. All Rights Reserved.

Michael “Mack” Frankfurter Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.