The Keynesian Endgame

Economics / Economic Theory Apr 12, 2013 - 12:20 PM GMTBy: MISES

David Stockman writes: Even the tepid post-2008 recovery has not been what it was cracked up to be, especially with respect to the Wall Street presumption that the American consumer would once again function as the engine of GDP growth. It goes without saying, in fact, that the precarious plight of the Main Street consumer has been obfuscated by the manner in which the state’s unprecedented fiscal and monetary medications have distorted the incoming data and economic narrative.

David Stockman writes: Even the tepid post-2008 recovery has not been what it was cracked up to be, especially with respect to the Wall Street presumption that the American consumer would once again function as the engine of GDP growth. It goes without saying, in fact, that the precarious plight of the Main Street consumer has been obfuscated by the manner in which the state’s unprecedented fiscal and monetary medications have distorted the incoming data and economic narrative.

These distortions implicate all rungs of the economic ladder, but are especially egregious with respect to the prosperous classes. In fact, a wealth-effects driven mini-boom in upper-end consumption has contributed immensely to the impression that average consumers are clawing their way back to pre-crisis spending habits. This is not remotely true.

These distortions implicate all rungs of the economic ladder, but are especially egregious with respect to the prosperous classes. In fact, a wealth-effects driven mini-boom in upper-end consumption has contributed immensely to the impression that average consumers are clawing their way back to pre-crisis spending habits. This is not remotely true.

Five years after the top of the second Greenspan bubble (2007), inflation-adjusted retail sales were still down by about 2 percent. This fact alone is unprecedented. By comparison, five years after the 1981 cycle top real retail sales (excluding restaurants) had risen by 20 percent. Likewise, by early 1996 real retail sales were 17 percent higher than they had been five years earlier. And with a fair amount of help from the great MEW (measurable economic welfare) raid, constant dollar retail sales in mid-2005 where 13 percent higher than they had been five years earlier at the top of the first Greenspan bubble.

So this cycle is very different, and even then the reported five years’ stagnation in real retail sales does not capture the full story of consumer impairment. The divergent performance of Wal-Mart’s domestic stores over the last five years compared to Whole Foods points to another crucial dimension; namely, that the averages are being materially inflated by the upbeat trends among the prosperous classes.

For all practical purposes Wal-Mart is a proxy for Main Street America, so it is not surprising that its sales have stagnated since the end of the Greenspan bubble. Thus, its domestic sales of $226 billion in fiscal 2007 had risen to an inflation-adjusted level of only $235 billion by fiscal 2012, implying real growth of less than 1 percent annually.

By contrast, Whole Foods most surely reflects the prosperous classes given that its customers have an average household income of $80,000, or more than twice the Wal-Mart average. During the same five years, its inflation-adjusted sales rose from $6.5 billion to $10.5 billion, or at a 10 percent annual real rate. Not surprisingly, Whole Foods’ stock price has doubled since the second Greenspan bubble, contributing to the Wall Street mantra about consumer resilience.

To be sure, the 10-to-1 growth difference between the two companies involves factors such as the healthy food fad, that go beyond where their respective customers reside on the income ladder. Yet this same sharply contrasting pattern is also evident in the official data on retail sales.

* * *

That the consumption party is highly skewed to the top is born out even more dramatically in the sales trends of publicly traded retailers. Their results make it crystal clear that Wall Street’s myopic view of the so-called consumer recovery is based on the Fed’s gifts to the prosperous classes, not any spending resurgence by the Main Street masses.

The latter do their shopping overwhelmingly at the six remaining discounters and mid-market department store chains—Wal-Mart, Target, Sears, J. C. Penney, Kohl’s, and Macy’s. This group posted $405 billion in sales in 2007, but by 2012 inflation-adjusted sales had declined by nearly 3 percent to $392 billion. The abrupt change of direction here is remarkable: during the twenty-five years ending in 2007 most of these chains had grown at double-digit rates year in and year out.

After a brief stumble in late 2008 and early 2009, sales at the luxury and high-end retailers continued to power upward, tracking almost perfectly the Bernanke Fed’s reflation of the stock market and risk assets. Accordingly, sales at Tiffany, Saks, Ralph Lauren, Coach, lululemon, Michael Kors, and Nordstrom grew by 30 percent after inflation during the five-year period.

The evident contrast between the two retailer groups, however, was not just in their merchandise price points. The more important comparison was in their girth: combined real sales of the luxury and high-end retailers in 2012 were just $33 billion, or 8 percent of the $393 billion turnover reported by the discounters and mid-market chains.

This tale of two retailer groups is laden with implications. It not only shows that the so-called recovery is tenuous and highly skewed to a small slice of the population at the top of the economic ladder, but also that statist economic intervention has now become wildly dysfunctional. Largely based on opulence at the top, Wall Street brays that economic recovery is under way even as the Main Street economy flounders. But when this wobbly foundation periodically reveals itself, Wall Street petulantly insists that the state unleash unlimited resources in the form of tax cuts, spending stimulus, and money printing to keep the simulacrum of recovery alive.

Accordingly, the central banking branch of the state remains hostage to Wall Street speculators who threaten a hissy fit sell-off unless they are juiced again and again. Monetary policy has thus become an engine of reverse Robin Hood redistribution; it flails about implementing quasi-Keynesian demand–pumping theories that punish Main Street savers, workers, and businessmen while creating endless opportunities, as shown below, for speculative gain in the Wall Street casino.

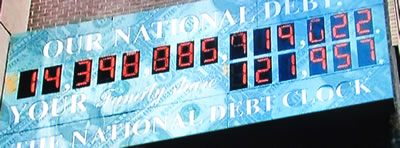

At the same time, Keynesian economists of both parties urged prompt fiscal action, and the elected politicians obligingly piled on with budget-busting tax cuts and spending initiatives. The United States thus became fiscally ungovernable. Washington has been afraid to disturb a purported economic recovery that is not real or sustainable, and therefore has continued to borrow and spend to keep the macroeconomic “prints” inching upward. In the long run this will bury the nation in debt, but in the near term it has been sufficient to keep the stock averages rising and the harvest of speculative winnings flowing to the top 1 percent.

The breakdown of sound money has now finally generated a cruel endgame. The fiscal and central banking branches of the state have endlessly bludgeoned the free market, eviscerating its capacity to generate wealth and growth. This growing economic failure, in turn, generates political demands for state action to stimulate recovery and jobs.

But the machinery of the state has been hijacked by the various Keynesian doctrines of demand stimulus, tax cutting, and money printing. These are all variations of buy now and pay later—a dangerous maneuver when the state has run out of balance sheet runway in both its fiscal and monetary branches. Nevertheless, these futile stimulus actions are demanded and promoted by the crony capitalist lobbies which slipstream on whatever dispensations as can be mustered. At the end of the day, the state labors mightily, yet only produces recovery for the 1 percent.

David Stockman was director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan, serving from 1981 until August 1985. He was the youngest cabinet member in the 20th century. See David Stockman's article archives.

© 2013 Copyright David Stockman - All Rights Reserved Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.