What Next For The Euro-Zone?

Economics / Eurozone Debt Crisis Jul 04, 2012 - 08:43 AM GMTBy: Victoria_Marklew

The European Union has just completed its 20th "make or break" Summit in a little over two years, and actually managed to beat expectations. Two key agreements were reached on June 28-29: expanding the remit of the two bailout funds - the temporary European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and permanent European Stability Mechanism (ESM) - to include sovereign debt purchases and eventually direct banking sector support; and creating a unified banking regulator for the Euro-zone under the auspices of the European Central Bank (ECB). These apparently-small steps are actually quite far reaching. The Summit outcome also indicates that, faced with really significant risks - in this case, unsustainable funding pressures on the Spanish and Italian sovereigns - the politicians are still willing to make some of the compromises necessary to support the Euro-zone. In our opinion, this combination of muddle-through and compromise in the face of crisis will lead to a closer fiscal union over the coming years. However, we also think that the likelihood that Greece will not be a member of the Euro-zone by end-2013 has risen to over 60%.

The European Union has just completed its 20th "make or break" Summit in a little over two years, and actually managed to beat expectations. Two key agreements were reached on June 28-29: expanding the remit of the two bailout funds - the temporary European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and permanent European Stability Mechanism (ESM) - to include sovereign debt purchases and eventually direct banking sector support; and creating a unified banking regulator for the Euro-zone under the auspices of the European Central Bank (ECB). These apparently-small steps are actually quite far reaching. The Summit outcome also indicates that, faced with really significant risks - in this case, unsustainable funding pressures on the Spanish and Italian sovereigns - the politicians are still willing to make some of the compromises necessary to support the Euro-zone. In our opinion, this combination of muddle-through and compromise in the face of crisis will lead to a closer fiscal union over the coming years. However, we also think that the likelihood that Greece will not be a member of the Euro-zone by end-2013 has risen to over 60%.

How Did We Get Here?

Before looking at the developments of recent weeks, we'll start by taking a step back and reminding ourselves of how we got to a time where debt pressures and concerns about potential Euro-zone collapse have dominated the headlines for two years straight.

When the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was first being planned back in the early 1990s, then-European Commission President Jacques Delors and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl had envisaged it as part of a wider political union, the logical culmination of the ever-wider and deeper trading bloc now known as the European Union. Even the Bundesbank, Germany's central bank, argued at the time that monetary union would not work without political union. But it quickly became apparent that Europe was not ready for this, so EMU's architects settled for a monetary union only and assumed that macroeconomic convergence would inevitably lead to closer fiscal and political union. The Maastricht Treaty (which came into force in November 1993) set the groundwork for EMU. It included the criteria that EU states would have to meet in order to adopt the new common currency, with specific targets for inflation, fiscal deficit and debt ratios to GDP, currency stability and nominal interest rates. The aim of Maastricht was to ensure that there would still be price stability within the Euro-zone even with the inclusion of new members.

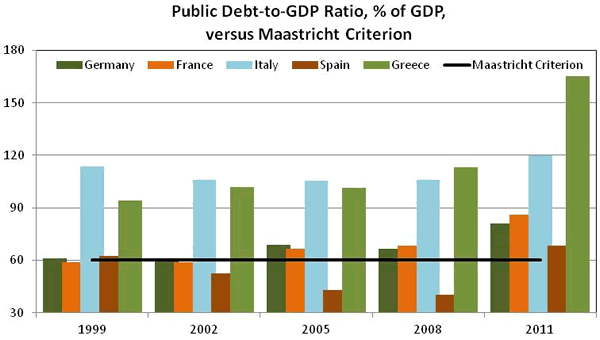

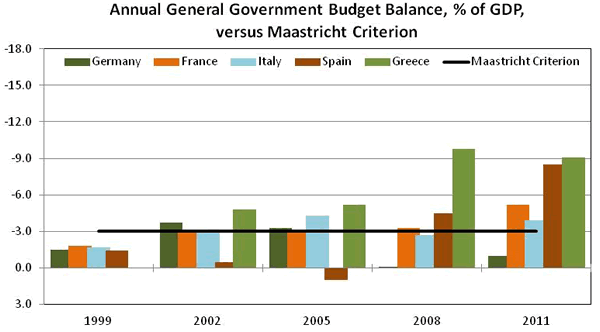

To ensure that members kept to their prudent ways even after joining, the EU then approved the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) in 1997. This called for fiscal monitoring by the European Commission and the Council of Ministers, and stipulated that Euro-zone members would have to maintain an annual general government deficit no higher than 3% of GDP and a national debt lower than 60% of GDP (or at least "approaching" that value - a fudging of the requirements so that high-debt Belgium and Italy would still be allowed to join the 'zone with the assumption that they would keep reducing their debt ratios). The Pact called for a series of increasingly-stringent warnings for violators, culminating in sanctions against offenders. The unspoken intent behind Maastricht and especially behind the SGP was "don't saddle the prudent members with the consequences of Italian and Greek profligacy."

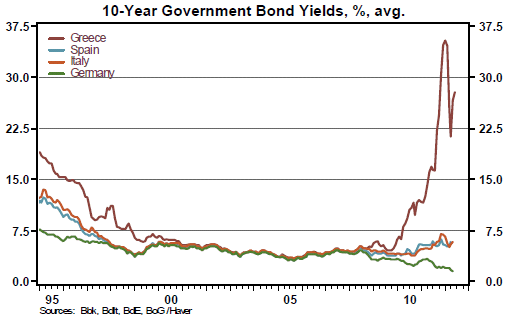

With the launch of the euro in 1999, the markets also bought into the convergence story, acting as if there was effectively a common Euro-zone bond market and a federal Europe. Lower yields led to a flood of cheap credit into the "converging" countries such as Greece (which joined in 2001), Portugal and Spain, despite the fact that their economies were nowhere near as competitive as the likes of Germany and the Netherlands. The result was a massive increase in public and private debt in many countries.

Meanwhile, it quickly became apparent that the SGP was unenforceable - largely because the two countries that had been among its strongest proponents, France and Germany, went on to run "excessive" deficits for some years. These two also have a large proportion of the votes in the Council of Ministers, the body that has to approve sanctions. In March 2005 the Council amended the Pact, saying it was responding to criticisms of insufficient flexibility while making the pact more enforceable. The 3% deficit and 60% debt ceilings were maintained, but the decision to declare a country in excessive deficit could now be more loosely interpreted, taking into account the longer-run "cyclically adjusted" budget, any prolonged periods of slow growth, and the possibility that the deficit is related to "productivity-enhancing procedures" - in other words, enough wiggle room to waive Paris and Berlin's violations and to ensure that real sanctions would never be applied.

Data: Eurostat

Progress In The Last Two Years

The prevailing wisdom says that the slow European decision-making process over the past two years has not resulted in any real changes. Certainly there have been no "decisive" moments of rapid institutional change but there have been a series of incremental steps that have brought us to the point that debate about a true fiscal union is no longer a pipe dream.

The revelations about the true state of Greece's fiscal picture that began in December 2009 triggered the subsequent EU-IMF bailout for that country and put the focus of markets and policy-makers firmly on the issue of European debt levels. As a result, consensus has developed around the need for fiscal consolidation and a number of countries have implemented constitutional amendments that aim at balanced budgets. In recent months debate has coalesced around the need for closer fiscal union. The December 2011 intergovernmental fiscal agreement - accepted by 25 of the 27 EU members and now wending its way through various national approval processes - calls for reinforcement of the existing rules on excessive deficit procedures, making them more automatic; as well as a requirement to submit draft budgets to the European Commission for approval. In effect, this marks a return to the original Stability and Growth Pact parameters. The carrot is that countries must sign up to the agreement if they want to get access to any form of funding support from the ESM.

Meanwhile, the creation of the temporary EFSF in 2010, and the February 2011 agreement to create a permanent successor ESM, marked a major step forward. The EFSF is a limited liability corporation registered in Luxembourg. Euro-zone states guarantee a pre-arranged amount of assets that the EFSF holds, allowing the Fund to then issue bonds or other debt instruments on the capital markets. The permanent ESM will also be based in Luxembourg but will be an intergovernmental institution, with a Board of Governors made up of the Euro-zone's finance ministers (the "Eurogroup"). The Mechanism will have a core capital base of €80 billion that will be paid in by Euro-zone members in stages (with an additional €620 billion in callable capital), allowing it a total lending capacity of €500 billion. Lending decisions and their terms will be made by "mutual agreement" by the Board.

The one European institution that does appear to have acted in a decisive manner has been the ECB, which has significantly pushed the bounds of its remit. In the past two years it has widened considerably the range of collateral that it will accept from banks for its funding operations; has pledged to supply 'zone banks with unlimited liquidity (recently extending that pledge until early 2013); and most controversially, has bought the debts of stressed sovereigns in the secondary markets. It was this latter step that prompted the resignations last year first of Bundesbank President Axel Weber in April and then of the ECB's Chief Economist Juergen Stark in September, in protest that the purchases broke the taboo against monetary financing of governments.

Toward A European Federation?

Many current EU leaders (but not all) say they want "more Europe" but they disagree on what that might look like and on how to get there. In broad terms, Berlin exemplifies the view that there should be more control and oversight before it will accept a greater sharing of the burdens. Paris belongs to the camp that wants more "solidarity" (sharing of burdens) before more control - similar to the positions of their respective governments 20 years ago.

Germany envisages closer fiscal coordination whereby a country that does not meet the rules loses control over its policies to a European authority that has the power to impose tax hikes and/or spending cuts. France, Italy and Spain are in favor of debt mutualization and of moves toward a banking union with a common deposit guarantee and EU-wide bank resolution fund. But France in particular is less than enthusiastic about ceding policy-making powers to Brussels. It is not clear whether any of these proposals would apply to the wider EU or whether they might be applied only to the Euro-zone. But among the non-Euro-zone countries, the UK wants nothing to do with a centralized banking regulator. Similarly, Czech PM Necas has firmly ruled out support of a banking union, fearing that unified regulation would remove the ability of Czech regulators to oversee and limit capital and asset flows between Czech banks and their foreign parent companies.

And of course fiscal policy - the right to tax and spend - is fundamental to a modern government's sense of self. Shifting even a small portion of that power to a central body represents a major step toward a federal Europe. Would any French president allow an institution in Brussels to judge its policy settings? It might, if the only alternative appeared to be the collapse of the euro itself.

What Do The Voters Think?

From its earliest inceptions in the 1950s, each stage of the European unification project has been based on an assumption that limiting membership to democracies would be enough to ensure that the overall edifice is democratic. In the early post-war years there was also an unspoken agreement that allowing for broad-based voter input could encourage "populism" - raising the specter of Nazi- and communist-style manipulation of mass voting blocs. This elitist view held that enlightened democratically-elected leaders could do what is best for the people. Voters mostly went along with this as long as each step of the European project did not appear to have much obvious (negative) impact on their daily lives. Even so, French voters only backed the Maastricht Treaty by 51.05% in a September 1992 national referendum, and in recent years most governments have gone out of their way not to subject the various EU treaties and agreements to national votes.

Not surprisingly, European parliamentary election turnouts have been declining steadily across the EU since direct elections were introduced in 1979. Today, it's probably fair to say that an increasingly large proportion of EU voters equate "Europe" with faceless bureaucrats and immoral bankers who force ordinary folks to swallow spending cuts and tax hikes. There has also been a marked increase in support for extreme-right parties in recent years, with their habitual xenophobia morphing into anti-euro sentiments.

It is finally dawning on national leaders that the voters are getting antsy - nine of the Euro-zone's 17 national governments have seen a change in leadership in the past three years and questions about sovereign bailouts, debt mutualization and even the survival of the euro itself have become part of the national political debate. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble has said that his country will eventually have to hold a referendum on the future of the European Union, in particular over whether to transfer more rights to Brussels. The German Constitutional Court has repeatedly warned that the German parliament should have a greater say in decisions related to the various bailout mechanisms. Newly-elected French PM Jean-Marc Ayrault has said that national parliaments should provide more democratic control if Europe adopts more integrated economic governance as the European parliament alone is not sufficient.

Will The Euro-Zone Survive?

The EU's modus operandi of the past two years has been one of "muddle through" while trying to keep the 'zone intact - but we think that the likelihood that this will continue has dropped to around 30% and it is no longer our base case. The slow pace of reaction in Europe's capitals has worsened the risk of unintended consequences, including a credit strike that leads to wider Euro-zone collapse. But we think it has also increased the probability that, sometime before end-2013, Greece will default on its debts and leave the 'zone.

Governments are deeply divided over what "Europe" means, markets are pressing for swift action that is highly unlikely to be forthcoming except in extremis, and voters appear utterly disillusioned over the whole mess. Given this set of circumstances, there is a not-insignificant risk that the 'zone could be undone within the next three years thanks to some combination of national political pressures and creditor fatigue - there has already been a pronounced "re-nationalization" of funding markets. A wider Euro-zone collapse could mean anything from the withdrawal of a few countries (perhaps Greece, Portugal and Spain); to the retention of only a euro-core built around Germany and a handful of others; to a total collapse and recreation of 17 separate currencies. A wider collapse would likely mean real GDP contraction of anywhere from 5% to 10% or higher for the former 'zone members.

However, the likelihood of this scenario unfolding in one form or another is still small - we'd hazard a guess at less than 10%. The EU in general and the 'zone in particular have successfully created close, extensive financial and trade linkages between their members. It would take an enormous shock to dissolve the Euro-zone as a whole. In addition, there is still widespread political support in ruling circles for the Euro-zone to continue. The creation of the EU in its various stages was a political decision and so was the creation of the Euro-zone. Austrian Finance Minister Maria Fekter reminded her parliament before the most recent Summit that "Europe is our guarantor of peace." Heading into the Summit, Italy and Spain publicly and unequivocally warned that their ability to fund their sovereign obligations was at stake. Faced with this stark risk, the outcome of the Summit itself - Germany accepting what are effectively the first steps toward debt sharing and a common banking regime, while France, Italy and Spain back off on pressure for more rapid and full-scale debt mutualization - is indicative of the kind of political support that still exists for the Euro-zone.

It is unlikely that a national leader will want to go down in history as having been responsible for the collapse of the euro. But that doesn't mean that the current 17 will still be members in three years' time. The past six months have seen a marked shift in the rhetoric from not only commentators and market players but also EU political leaders. A new consensus appears to be building that the 'zone can survive without Greece as a member.

What Might "Grexit" Look Like?

A few years ago, Athens admitted that it had fudged the numbers in order to meet the Maastricht criteria and win (delayed) admittance to the Euro-zone. This was hardly a surprise to most commentators - the decision to let the Greeks join in 2001 was clearly based more on political considerations that on the state of the Greek economy. But with their voters increasingly restive and cheap credit a thing of the past, the rest of the 'zone can no longer afford to overlook Greek transgressions. Hence, the "revelations" about the true state of the Greek national finances have increasingly hardened opinion in other European capitals, particularly over the past six months. Contrast the sound-bites about how much progress has been made by Portugal, Ireland, and even Spain in their various reform programs, with the increasingly-snippy comments about how far Greece still has to go.

With the ECB having set the precedent of being more flexible about what it will fund and how, the EU leadership agreeing to expand the remit of the EFSF/ESM bailout funds, and a hefty write-down of private sector holdings of Greek sovereign debt having passed off fairly smoothly in March, the probability that the Euro-zone will be reduced to 16 members by end-2013 has risen to over 60%.

Although the recent Greek election resulted in a "pro-euro" coalition government in Athens, and as much as 75% of Greek voters say they want to stay in the Euro-zone, 52% also cast their vote for parties opposed to the reforms needed to stay in the 'zone. No-one really knows what might trigger a "Grexit" or how the process would unfold. However, our base case is that, sometime in the next 18 months, the lending "troika" of the EU, ECB, and IMF will declare that Greece has failed to meet the terms of its aid program and will suspend financial assistance. It is also quite possible that this will be triggered after a sustained period of political turmoil and uncertainty in Greece and a succession of "emergency" aid measures on the part of the EU. Once financial assistance is finally suspended, Greece's funding situation would quickly become unsustainable. Capital flight out of the country would increase sharply, culminating in the declaration of a full debt default, some form of currency/capital controls and the announcement that Greece is withdrawing from the Euro-zone.

Outside Greece, a lot of commentators have started to talk about an "orderly" Greek exit. Such an event is likely to be anything but orderly for ordinary Greeks. The value of their savings would plummet along with a depreciating new drachma; imports would become scarce and expensive; hyperinflation would be a real risk. Depending on how the process unfolds, the rest of the EU would probably allow Greece to remain in the wider EU - if they didn't, the prognosis for Athens would be even worse thanks to loss of access to the free trade area.

"Orderly" really applies to the impact of a Greek withdrawal on the other members of the EU and in particular their ability to take decisive action to contain the negative effects. The ECB would likely have to flood the banking system with cash and prop up bond prices again. The end-June Summit agreed that the EFSF and ESM will be allowed to buy the sovereign bonds of distressed members in the primary and secondary markets and, once a common banking sector supervisory body is in place, will be able to lend directly to 'zone banks. The next six months will see plenty of wrangling over the details of these decisions and Euro-zone members will likely have to increase the size the permanent ESM at some point. The risk of untoward developments remains high. Nevertheless, once these mechanisms are in place - and the aim is to do so by end-2012 - contagion effects from a Greek exit could be contained more easily, without boosting individual sovereign debt levels and without needing endless Summits to come up with an agreed response.

Adding up the ECB's holdings of Greek sovereign bonds, the amount of debt owed by the Bank of Greece within the European banking system, and the debts owed to other EU members thanks to the loans made as part of the bailouts, it appears that the Greek government owes the rest of the EU close to €300 billion. Greek companies and households owe international banks somewhere around €90 billion (as of end-2011). Most of these debts would likely never be repaid in the event of a default and "Grexit." Between these defaults, and a drop in confidence and rise in funding costs for the remaining 16, an "orderly" Greek exit could result in Euro-zone real GDP contracting at least 2% in the first year. Recovery in subsequent years would depend on the process remaining "orderly."

Faced with the alternative of widespread market contagion and a collapse of confidence in the euro itself, even the Bundesbank may be willing to go along with "decisive" steps. That certainly seems to be the thinking in a number of Europe's capitals, where it is increasingly assumed that governments will be able to sell closer union to their voters if it doesn't include the profligate Greeks and if the alternative is chaos. The EU does have a track record of making substantial leaps forward during a time of crisis, but the consequences of getting it wrong this time around are enormous.

By Victoria Marklew

The Northern Trust Company

Economic Research Department - Daily Global Commentary

Victoria Marklew is Vice President and International Economist at The Northern Trust Company, Chicago. She joined the Bank in 1991, and works in the Economic Research Department, where she assesses country lending and investment risk, focusing in particular on Asia. Ms. Marklew has a B.A. degree from the University of London, an M.Sc. from the London School of Economics, and a Ph.D. in Political Economy from the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of Cash, Crisis, and Corporate Governance: The Role of National Financial Systems in Industrial Restructuring (University of Michigan Press, 1995).

Copyright © 2012 Victoria Marklew

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of The Northern Trust Company. The Northern Trust Company does not warrant the accuracy or completeness of information contained herein, such information is subject to change and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.