Why Innovation Needs Big Government

Economics / Government Intervention May 31, 2011 - 04:57 AM GMTBy: Ian_Fletcher

Most people realize that the Federal budget deficit and the trade deficit are serious problems. Unfortunately, as I have argued previously, few people grasp the importance of another big deficit in our economy, without which it will be extremely hard to fix the first two: our innovation deficit.

Most people realize that the Federal budget deficit and the trade deficit are serious problems. Unfortunately, as I have argued previously, few people grasp the importance of another big deficit in our economy, without which it will be extremely hard to fix the first two: our innovation deficit.

Simply put: despite appearances to the contrary, our economy is not innovative enough. And it’s costing us, big-time.

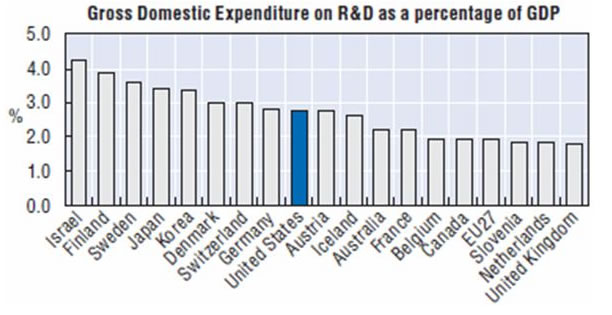

Despite our smug self-image as a global innovation leader, the U.S. actually only ranks in the middle of the pack for resources committed to innovation. See the chart below. (Source.)

Of course, spending money on problems isn’t everything. But it is also true that you generally get what you pay for. So unless our R&D is somehow more efficient dollar-for-dollar than that of other nations, we’re not setting the pace here.

Our other big problem, of course, is that even when we do succeed in out-innovating other nations, we often can’t hang onto the industries we create. In fact, we have a long record of originating technologies and then “losing our birthright” of commercial dominance in them. To give just a few examples:

high-fidelity sound systems

color television

digital watches

videocassette recorders

semiconductor memories

semiconductor production equipment (like steppers, the machines that “print” computer chips onto silicon)

flat panel displays

robots

lithium-ion batteries

advanced ceramics (turbine blades, not coffee mugs)

The weakness of our innovation performance is masked for the time being by the fact that innovations often have long lead times between the stages of the so-called “technology life cycle.” That is, decades can pass between the beginning and the end of the following process:

1. The key underlying science is discovered or key technology invented.

2. The first (exotic and expensive) commercial applications appear.

3. The technology gradually achieves adoption in all uses where it is appropriate.

4. The know-how to build the technology diffuses so much that it becomes a low-cost commodity product that any reasonably competent nation can make.

As a result, a nation that was once on the forefront of innovation can still be harvesting technological positions it previously planted years later. We’re coasting.

This coasting effect is enhanced by the presence of so-called “standards lock-in” protecting the oligopolies of companies like Microsoft and Intel. Microsoft’s products are, as anyone who uses them knows, in many ways abysmal: its desktop operating system delivers a user experience that is no faster or more reliable than the one sold a dozen years ago. People keep using it because of their need to interface with the installed base of other Microsoft users. Intel is less of a technological laggard, but it still commands a fat market share, and premium prices, based on the difficulty of computer manufacturers adapting to the use of alternative chips.

Other lesser-known companies and industries enjoy similar effects. But these effects are a wasting asset which will not last forever. They are vulnerable to both gradual encroachment and to sudden technology shocks that render their existing products obsolete overnight.

Another factor masking America’s innovation decline is the short-term gains from offshoring, which can make declining tech companies seem to boom as they ramp up profits by inexorably selling off their crown jewels. When a company offshores the least-productive, and least profitable, parts of its supply chain, both its productivity and profitability must, by definition, go up, in the short run. In the long run, however, this can lead to an insidious logic according to which, in the words of aerospace engineer Dr. L. J. Hart-Smith, who wrote a prescient critique of how Boeing was slowly outsourcing itself to death, the company decides “to outsource everything except a little Boeing decal to slap on the nose of the finished airplane.”

So how can we restore America’s innovation engine?

As I argued in a previous article, the key bottleneck in America’s innovation system isn’t, as many Republicans seem to think, that the government hamstrings would-be innovators with excess regulation or taxes their profits to death. Outside a few industries with big risks to the environment (nuclear energy) or public health (pharmaceuticals), the regulatory burden is, in fact, relatively light. Neither does our government impose confiscatory taxation on successful innovators.

Instead, the key bottleneck in our innovation supply chain is what we can call useful unpatentable ideas. (The more sophisticated term is “infratechnologies.”) These are technological innovations which cannot themselves be commercialized. But innovations that can be commercialized and sold for profit cannot take place without them. As a result, the private sector tends to neglect them.

To take one example: nanotechnology is probably the first major technology since the steam engine in which the U.S. is not the dominant player, research in this area being divided roughly equally between the U.S., Europe, and the Far East. And commercial nanotech companies depend, according to Greg Tassey of the National Institute of Standards and Technologies, upon the following infratechnologies:

• Techniques for measuring the shapes, dimensions, and electrical characteristics of the

various molecules making up nanoscale devices.

• Techniques for manipulating and measuring the spin of individual electrons.

• Scientific and engineering data for characterizing the fundamental physical behavior

and long-term reliability of new nanoelectronic materials.

Note that the words “techniques” and “data” figure prominently in the above descriptions. As noted, these are not (usually!) things that can be directly commercialized or patented. Nor are they academic pure science that the National Science Foundation will fund.

Reigning neoclassical economics assumes (often without realizing it) that new technologies grow automatically from advances in pure science. It also assumes that these new technologies automatically commercialize themselves. But if, as noted, there are important gaps in the “innovation supply chain,” this isn’t true. Pure laissez faire doesn’t work well in technology any better than it does in other areas of economics.

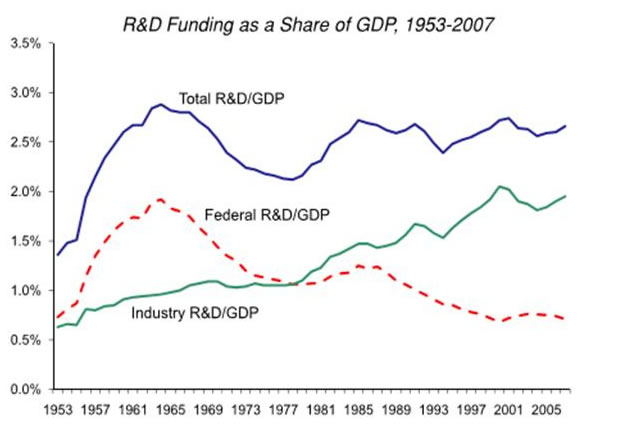

Back in the golden age of the American economy , the Federal government used to fill these gaps much better than it does today. In 1965, it funded 65 percent of all American R&D. But it has been walking away from this task for decades, as the chart below makes clear. (Source.)

One big problem for the U.S., as opposed to other countries, is that our publicly-funded R&D is dominated by mission-oriented agencies—NASA, the Defense Department, the National Institutes of Health, etc. These are fine institutions, but none of them is organized around the economic objective of increasing our GDP. They are all organized around non-economic missions: explore space, defend the nation, cure illness.

Other nations tend to focus R&D funding on what will improve their economies. For example, Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institute has one mission: technology development and commercialization. (One consequence is that private industry contributes about a third of its budget; leveraging money this way is key.) It is no accident that while our Defense Department produces 0.1 patent (an imperfect measure for infratechnology research, but it’s what’s available) per million dollars, ITRI generates twenty times that. (Source.)

Proposals have been made to remedy America’s shortfall in this field. In 2008, the liberal Brookings Institution and the industry-funded Information Technology and Innovation Foundation proposed a National Innovation Foundation along the lines of the existing National Science Foundation.

Beyond this, what else could we do? Here are some suggestions:

· Raise the average level of research and development (R&D) in manufacturing to six percent. This would be roughly a fifty percent increase from today. It wouldn’t push the entire manufacturing sector into the ultra-high R&D category characteristic of true high technology, but it’s a good benchmark of what level we need for the sector to be innovative across the broad range of categories we need.

· Shift American R&D more towards long-term “breakthrough” research, as opposed to short-term research oriented to next week’s product launch.

· Because long-term research is, by its nature, more speculative, encourage a “portfolio” approach in which many projects are pursued, only a few of which will reach fruition in any given time-frame, as opposed to a “bet the house” approach on one or two things.

· Increase the efficiency of America’s R&D spending by supporting a number of policies to this end, like regional technology clusters, supported in part by state governments. Some states are already doing this part on their own.

Ian Fletcher is the author of the new book Free Trade Doesn’t Work: What Should Replace It and Why (USBIC, $24.95) He is an Adjunct Fellow at the San Francisco office of the U.S. Business and Industry Council, a Washington think tank founded in 1933. He was previously an economist in private practice, mostly serving hedge funds and private equity firms. He may be contacted at ian.fletcher@usbic.net.

© 2011 Copyright Ian Fletcher - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.