The Economy When Capital Is Nowhere in Sight

Economics / Economic Theory May 11, 2011 - 01:05 PM GMTBy: Jeffrey_A_Tucker

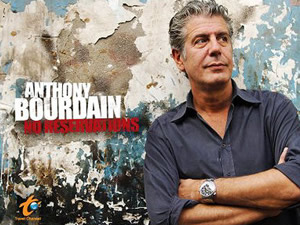

A Travel Channel episode of No Reservations, a cooking-focused show narrated by Anthony Bourdain, took viewers to Port-au-Prince, Haiti. I had heard that the show offered unique insight into the country and its troubles. I couldn't imagine how. But it turns out to be true. Through the lens of food, we can gain an insight into culture, and from culture to economy, and from economy to politics and finally to what's wrong in this country and what can be done about it.

A Travel Channel episode of No Reservations, a cooking-focused show narrated by Anthony Bourdain, took viewers to Port-au-Prince, Haiti. I had heard that the show offered unique insight into the country and its troubles. I couldn't imagine how. But it turns out to be true. Through the lens of food, we can gain an insight into culture, and from culture to economy, and from economy to politics and finally to what's wrong in this country and what can be done about it.

Through this micro lens, we gain more insight than we would have if the program were entirely focused on economic issues. Such an episode on economics would have featured dull interviews with treasury officials and IMF experts and lots of talk about trade balances and other macroeconomic aggregates that miss the point entirely.

Through this micro lens, we gain more insight than we would have if the program were entirely focused on economic issues. Such an episode on economics would have featured dull interviews with treasury officials and IMF experts and lots of talk about trade balances and other macroeconomic aggregates that miss the point entirely.

Instead, with the focus on food and cooking, we can see what it is that drives daily life among the Haitian multitudes. And what we find is surprising in so many ways.

In a scene early in the show set in this giant city after the earthquake, Bourdain and his crew stop to eat some local food from a vendor. He discusses its ingredients and samples some items. Crowds of hungry people begin to gather. They are doing more than gawking at the camera crews. They are waiting in the hope of getting something to eat.

Bourdain thinks of a way to do something nice for everyone. Realizing that in this one sitting, he is eating a quantity of food that would last most Haitians three days, he buys out the remaining food from the vendor and gives it away to locals.

Nice gesture! Except that something goes wrong. Once the word spreads about the free food — word-of-mouth in Haiti is faster than Facebook chat — people start pouring in. Lines form and get long. Disorder ensues. Some people step forward to keep order. They bring belts and start hitting. The entire scene becomes very unpleasant for everyone — and the viewer gets the sense that it is worse than we are shown.

Bourdain correctly draws the lesson that the solutions to the problem of poverty here are more complex than it would appear at first glance. Good intentions go awry. They were thinking with their hearts instead of their heads, and ended up causing more pain than was originally there in the first place. From this event forward, he begins to approach the problems of this country with a bit more sophistication.

The rest of the show takes us through shanty towns, markets, art shows, festivals, and parades — and interviews all kinds of people who know the lay of the land. This is not a show designed to tug at your heart strings in the conventional sort of way. Yes, there is obvious human suffering, but the overall impression I got was not that. Instead, I came away with a sense that Haiti is a very normal place not unlike all places we know from experience, but with one major difference: it is very poor.

By the time the show was made, the glamour of the postearthquake onslaught of American visitors seeking to help had vanished. One who remains is actor Sean Penn. Although he's known as a Hollywood lefty, he's actually living there, chugging up and down the hills of a shanty town, unshaven and disheveled, being what he calls a "functionary" and getting stuff for people who need it. He had no easy answers, and he had sharp words for American donors who think that dumping money into new projects is going to help anyone.

The people of Haiti in the documentary conform to what every visitor says about them. They are wonderfully friendly, talented, enterprising, happy, and full of hope. Like most people, they hate their government. Actually, they hate their government more than most Americans hate theirs. Truly, this is a precondition of liberty. There is a real sense of us-versus-them alive in Haiti, so much so that when the presidential palace collapsed in the recent earthquake, crowds gathered outside to cheer and cheer! It was the one saving grace of an otherwise terrible storm.

With all these enterprising, hard-working, and creative people, millions of them, what could possibly be wrong with the place? Well, for one thing, the earthquake destroyed most homes. If this had been the United States, this earthquake would not have caused the same level of damage. This led many outsiders to think that somehow the absence of building codes was the core of the problem, and hence the solution is more imposition of government control.

But the reality shows that this building-code notion is some sort of joke. The very idea that a government could somehow go around beating up people who provide shelter for themselves while failing to obey the central plan is simply laughable. Coercion of this sort would bring about no positive results and lead only to vast corruption, violence, and homelessness.

The core of the problem, says Robert Murphy, has nothing to do with a lack of regulations. The problem is the absence of wealth. It is obviously true that people prefer safer places to live, but the question is: what is the cost, and is this economically viable? The answer is that it is not viable, not in Haiti, not with this population that is barely getting by at all.

Where is the wealth? There is plenty of trade, plenty of doing, plenty of exchange and money changing hands. Why does the place remain desperately poor? If the market economists are correct that trade and commerce are the key to wealth, and there is plenty of both here, why is wealth not happening?

One can easily see how people can get confused, because the answer is not obvious until you have some economic understanding. A random visitor might easily conclude that Haiti is poor because somehow the wealth is being hogged by its northern neighbor, the United States. If we weren't devouring so much of the world's stock of wealth, it could be distributed more evenly and encompass Haiti too. Or another theory might be that the handful of international companies, or even aid workers, are somehow stealing all the money and denying it to the people.

These are not stupid theories. They are just theories — neither confirmed nor refuted by facts alone. They are only shown to be wrong once you realize a central insight of economics. It is this: trade and commerce are necessary conditions for the accumulation of wealth, but they are not sufficient conditions. Also necessary is that precious institution of capital.

What is capital? Capital is a thing (or service) that is produced not for consumption but for further production. The existence of capital industries implies several stages of production, or up to thousands upon thousands of steps in a long structure of production. Capital is the institution that gives rise to business-to-business trading, an extended workforce, firms, factories, ever more specialization, and generally the production of all kinds of things that by themselves cannot be useful in final consumption but rather are useful for the production of other things.

Capital is not so much defined as a particular good — most things have many varieties of uses — but rather a purpose of a good. Its purpose is extended over a long period of time with the goal of providing for final consumption. Capital is employed in a long structure of production that can last a month, a year, 10 years, or 50 years. The investment at the earliest (highest) stages has to take place long before the payoff circles around following final consumption.

As Hayek emphasized in The Pure Theory of Capital, another defining mark of capital is that it is a nonpermanent resource that must nonetheless be maintained over time in order to provide a continuing stream of income. That means that the owner must be able to count on being able to hire workers, replace parts, provide for security, and generally maintain operations throughout an extended period of production.

In a developed economy, the vast majority of productive activities consist in participation in these capital-goods sectors and not in final-consumption-goods sectors. In fact, as Rothbard writes in Man, Economy, and State,

at any given time, this whole structure is owned by the capitalists. When one capitalist owns the whole structure, these capital goods, it must be stressed, do him no good whatever.

And why is that? Because the test of the value of all capital goods is conducted at the level of final consumption. The final consumer is the master of the richest capitalist.

Many people (I've been among them) rail against the term capitalism because it implies that freedom is all about privileging the owners of capital.

But there is a sense in which capitalism is the perfect term for a developed economy: the development, accumulation, and sophistication of the capital-goods sector is the characteristic feature that makes it different from an undeveloped economy.

The thriving of the capital-goods sector was the great contribution of the Industrial Revolution to the world.

Capitalism did in fact arise at a specific time in history, as Mises said, and this was the beginning of the mass democratization of wealth.

Rising wealth is always characterized by such extended orders of production. These are nearly absent in Haiti. Most all people are engaged in day-to-day commercial activities. They live for the day. They trade for the day. They plan for the day. Their time horizons are necessarily short, and their economic structures reflect that. It is for this reason that all the toil and trading and busyness in Haiti feels like peddling a stationary bicycle. You are working very hard and getting better and better at what you are doing, but you are not actually moving forward.

Now, this is interesting to me because anyone can easily miss this point just by looking around Haiti where you see people working and producing like crazy, and yet the people never seem to get their footing. Without an understanding of economics, it is nearly impossible to see the unseen: the capital that is absent that would otherwise permit economic growth. And this is the very reason for the persistence of poverty, which, after all, is the natural condition of mankind. It takes something heroic, something special, something historically unique, to dig out of it.

Now to the question of why the absence of capital.

The answer has to do with the regime. It is a well-known fact that any accumulation of wealth in Haiti makes you a target, if not of the population in general (which has grown suspicious of wealth, and probably for good reason), then certainly of the government. The regime, no matter who is in charge, is like a voracious dog on the loose, seeking to devour any private wealth that happens to emerge.

This creates something even worse than the Higgsian problem of "regime uncertainty." The regime is certain: it is certain to steal anything it can, whenever it can, always and forever. So why don't people vote out the bad guys and vote in the good guys? Well, those of us in the United States who have a bit of experience with democracy know the answer: there are no good guys. The system itself is owned by the state and rooted in evil. Change is always illusory, a fiction designed for public consumption.

This is an interesting case of a peculiar way in which government is keeping prosperity at bay. It is not wrecking the country through an intense enforcement of taxation and regulation or nationalization. One gets the sense that most people never have any face time with a government official and never deal with paperwork or bureaucracy really. The state strikes only when there is something to loot. And loot it does: predictably and consistently. And that alone is enough to guarantee a permanent state of poverty.

Now, to be sure, there are plenty of Americans who are firmly convinced that we would all be better off if we grew our own food, bought only locally, kept firms small, eschewed modern conveniences like home appliances, went back to using only natural products, expropriated wealthy savers, harassed the capitalistic class until it felt itself unwelcome and vanished. This paradise has a name, and it is Haiti.

Jeffrey Tucker is the editor of Mises.org. Send him mail. See Jeffrey A. Tucker's article archives. Comment on the blog.![]()

© 2011 Copyright Ludwig von Mises - All Rights Reserved Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.