Does Economic Growth Cause Inflation?

Economics / Inflation Mar 16, 2011 - 10:30 AM GMTBy: Frank_Shostak

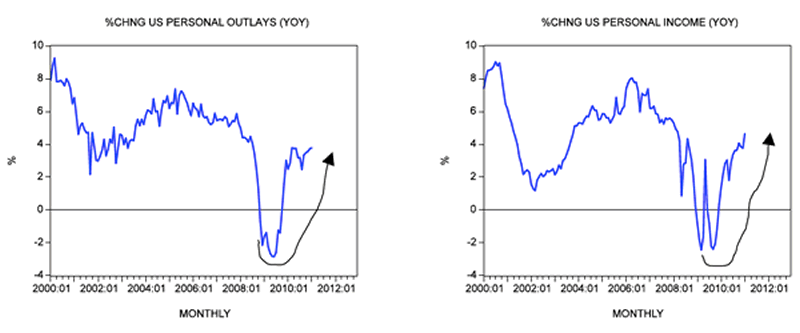

The yearly rate of growth of personal consumer outlays jumped from 2.5 percent in August last year to 3.8 percent this January.

The yearly rate of growth of personal consumer outlays jumped from 2.5 percent in August last year to 3.8 percent this January.

The growth momentum of personal income has been pushing ahead strongly since May last year.

Year-on-year, the rate of growth shot up from 1.8 percent in May to 4.6 percent in January.

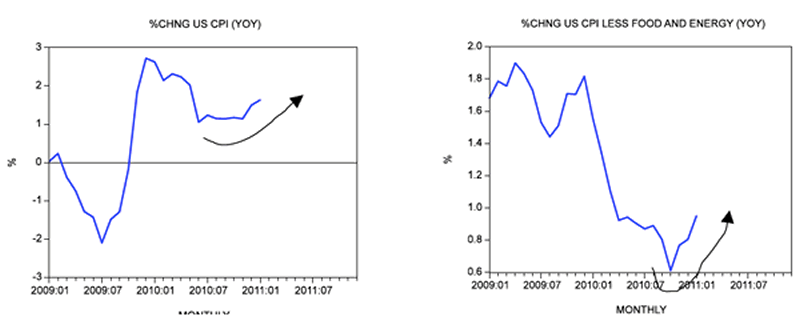

Most economists and various commentators, while expressing satisfaction that the US economy is starting to display signs of improvement, are also raising concerns that a further strengthening in the economy could trigger a higher rate of inflation. Indeed the growth momentum of both the consumer-price index and the consumer-price index less food and energy displays a visible strengthening. The yearly rate of growth of the CPI stood at 1.6 percent in January versus 1.1 percent in June last year. Meanwhile, the rate of growth of the CPI less food and energy stood at 1 percent in January against 0.6 percent in October.

Most experts are of the view that as the economy gains strength the Fed will have to step in at some stage and tighten its stance in order to keep the rate of inflation from getting out of control. Experts, however, caution that we are still not at this stage. The key reason is that the yearly rate of growth of the core consumer-price index, i.e., the CPI less food and energy, is well below the 2 percent target. According to experts, as long as this is the case the Fed should still be concerned with deflation rather than inflation. Hence, for the time being, experts assign a very low likelihood of the Fed tightening its stance soon. But why should economic growth be positively associated with a general increase in prices of goods and services?

Let us examine how prices in general could go up. The price of a good is the amount of dollars paid per unit of this good. So with all things being equal, an increase in the amount of dollars in the economy must lead to a general increase in prices of goods and services. Now, when we talk about economic growth, we mean an increase in the production of goods and services, i.e., an expansion in real wealth. Obviously then, for a given amount of money an increase in economic growth means a greater amount of goods and services, which must lead to a decline and not an increase in the prices of goods and services in general. (We now have more goods for the same amount of dollars.)

This simple analysis illustrates that an expansion of wealth, which promotes individuals' well being, cannot at the same time generate bad things such as a general increase in prices, which undermines people's living standards.

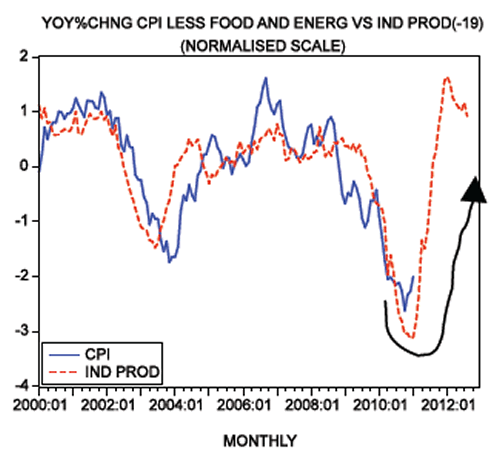

So, if what we are saying is correct, why are we currently observing a strengthening in the growth momentum of prices at the same time as a strengthening in economic growth? We suggest that from a strictly empirical perspective the yearly rate of growth of the CPI less food and energy is actually closely following the yearly rate of growth of industrial production lagged by 19 months. So from this relationship we can suggest that the growth momentum of the core CPI is likely to strengthen sharply in the months ahead.

But does the good correlation between the growth momentum of the core CPI and the lagged growth momentum of industrial production make sense? Again, why should more wealth, which raises people's living standards, also generate bad things such as a higher rate of inflation?

We suggest that the positive association between economic activity and price inflation is not on account of an expansion in real wealth but on account of an expansion of the money supply. The so-called total real economic growth cannot be quantified as such — it is not possible to add potatoes to tomatoes to obtain the meaningful total that would be required to calculate real economic growth. So-called economic growth is calculated from monetary turnover, which is deflated by a dubious price deflator. This means that what is labeled as economic growth is nothing more than the rate of growth of distorted monetary-turnover data.

According to mainstream thinking, the stronger the monetary pumping is, the stronger the pace of spending — and consequently the stronger the monetary income and the so-called real economy is going to be. In short, in this framework more money means more spending and this leads to stronger economic growth.

Contrary to this way of thinking, more money only undermines the process of real-wealth generation. This means that more money is bad news for the production of real wealth.

Consequently, with more money and less wealth, this means more money per unit of goods, i.e., a general increase in prices. Observe that what we have here is an increase in monetary turnover on account of monetary pumping, which is presented as a strengthening in real economic growth, and an increase in general prices on account of the monetary pumping. Hence, it is not surprising that we observe a positive association between the so-called strong economic activity and price inflation. Note again that the so-called strengthening in economic activity reflects the strengthening in monetary pumping. In fact what we have here is a situation wherein monetary pumping is positively associated with the strengthening of price inflation.

From here we can deduce that it is erroneous to suggest that stronger economic growth must lead to higher price inflation. As we have seen, on the contrary, stronger economic growth for a given money supply must lead to a fall in prices. Observe that the fall in prices here is the manifestation of real-wealth expansion. It means that a every holder of dollars can now have access to more real wealth, i.e., goods. Contrary to conventional thinking then, a fall in prices whilst real wealth is rising is great news.

A fall in prices whilst the economy is declining should also be regarded as good news because it reflects the liquidation of various bubble activities that undermine the process of real-wealth generation. (These bubble activities that have emerged on the back of previous loose monetary policy come under pressure as a result of a fall in the growth momentum of money.)

We can thus conclude that the so-called empirical positive association between economic growth and price inflation, which is labeled as the Phillips curve, and is regarded by almost all economists as natural law on par with the law of gravity, is a misleading concept. All that it describes is the fact that the variation in the rate of growth of the money supply must result in a variation in prices of goods and services over time. Now, as long as the machinery of wealth generation is still functioning, Fed policy makers can get away with the illusion that they can steer the economy by monitoring the Phillips curve.

However, once the wealth-generation machinery is severely damaged on account of the Fed's relentless tampering (its "counter-cyclical policies"), the illusion that the Fed can help the economy is shattered, and the economy sinks deeply into a black hole. Any attempt by the Fed to revive the economy by means of massive pumping only makes things much worse. Also, we find it extraordinary that Fed officials continue to push money on a massive scale at the same time as they try to assure the public that they are fighting inflation.

Conclusion

Most economists, while expressing satisfaction that the US economy may have entered a self-sustaining economic-expansion phase, are also concerned that a further strengthening in the economy could trigger a higher rate of inflation. Most experts are of the view that as the economy gains strength the Fed will have to step in at some stage and introduce a tighter stance in order to counter inflation. We suggest that it is questionable that genuine economic growth can lead to general price inflation.

Also, we maintain that the positive association between economic activity and price inflation is not on account of an expansion in real wealth but comes in response to the expansion in money supply. We maintain that, contrary to popular thinking, the recent strengthening in some key US economic data such as employment doesn't reflect economic strengthening but is simply a response to the strengthening of bubble activities that are setting in motion another economic bust.

Frank Shostak is an adjunct scholar of the Mises Institute and a frequent contributor to Mises.org. He is chief economist of M.F. Global. Send him mail. See Frank Shostak's article archives. Comment on the blog.![]()

© 2011 Copyright Frank Shostak - All Rights Reserved Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.