Return of Trade Tariff Wars

Economics / Global Financial System Oct 02, 2007 - 12:23 AM GMTBy: Gerard_Jackson

Kevin Rudd is signalling that a Labor Government would introduce another tariff regime. Rudd’s threat basically rests on two arguments, whether he knows it or not: The main one being that tariffs are needed to protect Australian manufacturing before it disappears. Then there is the subsidiary argument that tariffs are needed to protect jobs and real incomes. It is now time to give some basic economic facts another airing:

Kevin Rudd is signalling that a Labor Government would introduce another tariff regime. Rudd’s threat basically rests on two arguments, whether he knows it or not: The main one being that tariffs are needed to protect Australian manufacturing before it disappears. Then there is the subsidiary argument that tariffs are needed to protect jobs and real incomes. It is now time to give some basic economic facts another airing:

1. There can be no widespread persistent unemployment in a free market so long as there is sufficient land and capital available to employ people.

2. The view that free trade lowers real wages to the level of poor trading countries was scornfully dismissed by Professor Haberler who stressed that the argument that free trade “leads to an equalisation of factor prices is fundamentally false”. (Gottfried Haberler The Theory of Free Trade , William Hodge and Company LTD, 1950, first published in 1933, p. 38, pp. 194-95, pp. 250-51).

3. Wages can only be equalised if labour is mobile, i.e., there are no barriers to labour moving from low-wage countries to high-wage countries. Therefore, while free trade does not lower real wages an open borders policy would.

4. Wages are largely determined by the ratio of labour to capital: the more capital relative to labour, the higher wages will be.

5. Free trade causes countries to allocate factors of production to their most productive use thus raising total output and welfare.

The Treasury and the Reserve Bank pointed out some years ago that our then unemployment rate was not caused or aggravated by tariff cuts. Moreover, in a free labour market free trade brings about a more efficient allocation of labour and not persistent unemployment. Only when labour markets are prevented by wage-fixing from reallocating labour will unemployment emerge. Put another way, when the cost of hiring someone exceeds the value of that person’s output, he will not be hired. For example, if the daily value of a man’s output is $100 (and it is we as consumers that set the value, not capitalists) and a union demands $110 per day or nothing, then it will be nothing and the dole queue will grow longer. And this is what has been happening in Australia. Unfortunately it seems almost impossible to get this economic truth discussed in the Australian media, let alone accepted. (Even our conservative government seems unaware of this basic economic truth).

Even though the protectionists’ claim that free trade causes unemployment (as opposed to transitional unemployment which every economy continually experiences) has been shown by economic theory and empirical research to be without foundation. However, their accusation that free trade will lower real wages to the same level as our low-wage trading partners does deserve a considered reply, even though it too is without foundation.

What we may call, for the sake of the argument, the ‘equalisation theory’ seems on the surface to be quite reasonable. After all, do not market economists tell us that there is a tendency for the market to equalise the prices of all goods? True, they do. However, the vitally important proviso is that the good has to be mobile, i.e., transportable; the easier and cheaper it is to transport the good the greater will be the tendency toward price equalisation. It is obvious, for example, that it is the existence of immigration barriers that prevents workers from low-wage countries crossing into high-wage countries thus bringing about the international equalisation of wages.

There is also the argument that even though low-wage workers cannot migrate, exporting their products to high-wage countries will still have the effect of driving wages down. A more sophisticated version of this fallacy states that it will only be those employed in labour-intensive industries and whose products have to compete with cheap imports who will suffer significant wage cuts. (Ibid. pp. 250-51) Therefore importing cheap goods becomes a substitute for importing ‘cheap labour’. This view ignores the economic fact that wages in poor countries are largely determined by the ratio of labour to capital, just as they are in rich countries. Wages are low in poor countries because productivity is low, and this is low because workers have painfully little capital to work with.

Asia provides an excellent example of the truth that domestic productivity drives wages. A few years ago the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found that low wages in poor Asian countries are directly related to low productivity. This rather obvious finding also concluded, however, that their unit labour costs were actually close to the American level. This apparent paradox was the result of differences in productivity. So even though labour costs in the Philippines and Thailand, for example, were low relative to U.S. labour costs, they were high relative to the value of their product which.

Stephen Golub, an American economist, found that though Malaysian, Filipino, Indian and Thai manufacturing wages in 1990 were only about 15 per cent of the American level, so was average productivity. What is particularly interesting, though not surprising, is that Filipino, Indian and Malaysian unit labour costs exceeded the US level. Economic analysis makes it clear that Asian labour is not so ‘cheap’ after all. (Douglas A. Irwin Free Trade Under Fire , Princeton University Press, 2002, ch. 6). It should be clear that wage rates are determined by domestic conditions and not by international trade. In economic terms this means that it is rising productivity brought about by the use of more capital that increase real wages. (Paul Krugman, Pop Internationalism , The MIT Press, 1997, pp. 55-56).

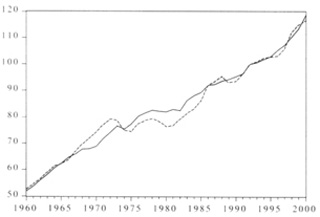

|

| Labor productivivity and labor compensation 1960-2000. Productivity is output per hour of all persons in the business sector. Data from the Council of Economic Advisers 2001, cited in Douglas A. Irwin's Free Trade Under Fire , Princeton University Press 2002, p. 96 |

|

| Real wages and labor productivity in manufacturing, South Korea 1972-93 (1987=100). Data from the World Bank Tables, cited in Douglas A. Irwin's Free Trade Under Fire , Princeton University Press 2002, p. 213. |

Despite economic theory and empirical evidence to the contrary, there are still those who preach that trade with poor countries is damaging the welfare of unskilled labourers in the West by depressing wages and causing unemployment. In 1992 International BusinessWeek published a lead article claiming that an increase in foreign trade was responsible for an “unprecedented surge in income equality between the most and least educated halves of the U.S. work force”. The argument that free trade with poor countries employing labour intensive techniques “would have a dramatic effect on lower-skilled workers” in the U.S. was forcefully put. It was predicted that poverty and unemployment would increase, the cost of welfare would rise and so would taxes, etc. The authors also tried to use the Stolper-Samuelson factor price equalisation theorem to support their dismal and, fortunately, baseless conclusions.

Before dealing with their claims on unemployment and falling incomes, we should first dispose of the authors’ theoretical justification for their conclusions. The equalisation theorem was developed from the Heckscher-Ohlin principle which basically stated that trading advantages between countries arose from their different factor endowments. Stolpert-Samuelson theorem extended it and stated that free trade will lead to factor prices being brought into line when the prices of their products are equalised. Therefore free trade becomes a substitute for factor mobility. So even though immigration laws prevent people from poor countries moving en mass to high-wage countries thus depressing wages, importing the products of their services will indirectly achieve the same effect.

Regardless of the authors’ support the equalisation theory does not hold up in the real world. Now the Heckscher-Ohlin principle led to the conclusion that factor equalisation between trading countries with different factor endowments would occur if they shared the same technology. But it was also assumed that the technology was almost perfectly divisible (perfect competition, homogenous capital and identical production functions were also assumed), meaning that it could be efficiently employed even on a tiny scale. Obviously, the key is in sharing the same technology. However, technology can only be applied through heterogeneous capital goods (investment) which cannot be perfectly divisible. This returns us to the Stolpert-Samuelson theorem which does not use the shared-technology restriction to support its conclusion that free trade will equalise factor incomes.

For a factor’s income (a wage for example) to be equalised in a situation where its mobility is confined to given areas, not only would it be necessary for the product of the ‘low-paid’ factor to (a) have free access to the other areas the high-wage factor would (b) also have to be specific. The reason for (b) should be obvious: the price of any factor cannot be driven down below the value of its alternative use. The price of labour is determined by the value of its marginal productivity; this in turn is determined by the size of the country’s capital structure. The smaller the capital structure relative to the population, therefore, the lower real wages will be and vice versa.

For American wages to fall in real terms the capital structure must either shrink or the labour force must grow faster than capital accumulation. The BusinessWeek article asserted that from 1979 to 1989 real pay and benefits for US factory workers fell by 6 per cent and that this confirmed the Stolpert-Samuelson theorem. Lestor Thurrow used similar logic to claim that the trade deficit had driven average wages down by 6 per cent by forcing a million people out of high-paying manufacturing jobs into low-paying services jobs. However, taking Thurrow’s figures at face value Paul Krugman showed that this alleged movement of labour could only have cut real wages by 0.3 per cent. I have already stated that labour would have to be specific for its wages to be forced down by low-wage imports until wage rates in both countries were equalised for the same type of labour.

To support the authors’ case imports from low-wage countries would have had to increase significantly; but such imports were only about 3 per cent of GDP at the time as opposed to 2 per cent in 1960. Moreover, if the Stolpert-Samuelson theorem seemed to be operating then the prices of traded goods produced by unskilled American labour would have fallen. This did not happen. Even if the prices of these goods had fallen, this would be in perfect keeping with free trade theory. Critics have forgotten that under comparative advantage factor combinations in each country are rearranged by price signals to increase total output. (I think that at this stage I should point out that the biggest threat to the wages of unskilled US labour is the presence of millions of illegal immigrants).

So if free trade did not cause falling real wages and increasing inequality, what did? Nothing. Richard Alm and Michael Cox, senior vice president and chief economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, did a statistical study in which they found that consumption — a good measure of economic welfare — had been rising through the 1970 and into the 1990s. (Alm and Cox, Myths of the Rich & Poor , Basic Books, 1999, ch. 5). So much for media reporting.

Oddly enough, once the Dems won the White House in 1992 the media lost all interest in wages and living standards. I wonder why?

How the Laffer curve really works

Does Australia’ s manufacturing decline hold a lesson for the US economy?

By Gerard Jackson

BrookesNews.Com

Gerard Jackson is Brookes' economics editor.

Gerard Jackson Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.