Macro Musings: Northern Rock Exposure

Stock-Markets / Global Financial System Sep 26, 2007 - 11:05 AM GMTBy: Justice_Litle

BY NOW YOU HAVE probably heard about Northern Rock—the UK mortgage bank that got, er, rocked.

BY NOW YOU HAVE probably heard about Northern Rock—the UK mortgage bank that got, er, rocked.

"It was a very British bank run," portfolio manager Tim Price reports. "The queues were orderly, but the emotional impact will scar people for generations."

What's remarkable is how long it's been since the last one. Northern Rock was Britain's first bank run since 1866.

To put that stretch of time in perspective, 1866 was the year dynamite and root beer were invented… the year Jesse James committed the first daylight bank robbery in Liberty, Missouri… the year that Canadian parliament met for the first time.

It's been a while, eh?

Symptoms and Causes

In comparison to the Brits, American bank runs are almost old hat. The run on the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust—considered the largest U.S. bank failure in history—was just 23 years ago. (Will the size record be broken before decade's end? Knock on wood…)

America is a land of bigness. (Big houses, big cars, big mortgages, and so on.) Texans in particular like to brag how everything is bigger where they come from. (This ticks off Alaskans no end.)

In regard to housing problems, though, the scope of America's bubble could look modest in comparison to other pops-in-progress.

Different markets will show different symptoms. Northern Rock, for example, didn't overdose on NINJA loans (no income, no job, no assets). Mortgage structures in the UK aren't quite as loopy as that.

No, the problem with Northern Rock—the UK's fifth largest mortgage bank—was reckless expansion fueled by easy credit. (Now that strikes a familiar chord.)

Three quarters of the bank's funding came from outside sources. For every pound sterling lent out, a mere 25 pence was backed by deposits. The hyper-aggressive lender got as stretched as its borrowers. When credit markets seized up, there was nowhere to turn.

The trouble with lenience

The bank run was not just a disaster for Northern Rock. It was also a public relations disaster for the Bank of England, and a black mark for Britain's Financial Services Authority.

Angry questions flew. How could a lender be so reckless? Where were the watchdogs who are supposed to keep banks safe? Why didn't the powers that be act sooner, before the panic spread?

The Bank of England managed to badly embarrass itself. Mervyn King, Britain's top central banker, might as well have advertised a clinic… "How to destroy credibility in two easy steps." First, take an irrationally hard line with no room for compromise. Second, cave in completely as the crisis deepens.

Post intervention, the old question looms. Should every lender with "too big to fail" status be saved at taxpayer expense? Bloomberg columnist Mark Gilbert captures the gist:

`Dear customer, congratulations on your new Hokey-Cokey Bank Plc deposit account! You'll enjoy substantially higher interest rates than you can get anywhere else, because we'll be betting your life savings in the local casino. Should the roulette ball land on red rather than black, no worries! The U.K. government guarantees your money!''

The economic term for this problem is "moral hazard."

Moral hazard is the risk of financial institutions behaving badly. If taxpayers foot the bill when things go kablooey, there is little reason not to go for broke.

Bailout-happy governments thus wind up encouraging a sort of "socialism for the rich," as Jim Grant puts it, in which risky bets are financed by the treasury. It's like flipping a coin. Heads and Wall Street wins… tails and taxpayers lose. (Keeping in mind, too, that inflation is a hidden regressive tax.)

More northern news

At least the Brits can take solace in their currency.

The pound has cracked US $2.00… a level not seen since 1992. (Londoners will find Manhattan charmingly cheap these days—not so the other way round.)

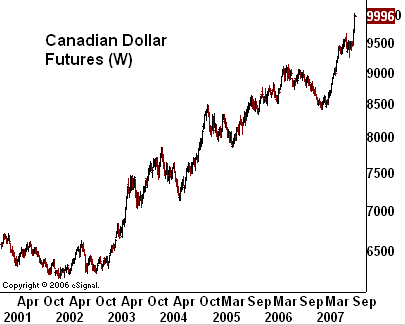

Furthermore, the Canadian dollar (aka the Loonie) is trading roughly at parity with the greenback. This last happened in 1976.

It's not a big psychological deal to see the pound above two bucks. Europe has been expensive (from an American standpoint) for a while now, and the yanks don't pay as much attention to what's happening "across the pond."

But the Canuck Buck at $1.00… now that's different. Canada is America's number one trading partner. There is a lot of commerce… a lot of border crossing (on the longest shared border in the world)… a lot of talk.

If the Loonie can trade at parity, why can't it go even higher? And how low can the greenback sink? An important mental threshold may be breached here.

A friend in need

If moral hazard is a problem for central banks at home, it is an even bigger problem abroad.

The United States, you see, has a credit addiction much like Northern Rock's.

The British mortgage bank fueled its expansion by aggressively tapping the capital markets. The US has fueled the growth of recent years by tapping other countries' wallets. (If a financial institution can stake its existence on outside funding, why not an empire?)

For Northern Rock, the credit lines disappeared just when needed most. The same thing could happen to the United States… and if it does, the dollar will tell the story.

People and institutions have credit ratings assigned to them. John Q. Public's credit rating helps determine how much interest he pays for that mortgage or auto loan. Corporate ratings determine how cheaply a company can borrow funds. Debt ratings are supposed to tell investors how risky a particular bond is.

The United States government doesn't have a true credit rating. Uncle Sam's "default risk" is pegged at zero… which makes an odd kind of sense, as the payment is just worthless paper anyway. It's a confidence game. The linchpin is psychology.

The dollar's exchange rate in the open market, then, is a sort of proxy for America's perceived creditworthiness in the eyes of the rest of the world.

As the dollar falls… and falls… and then falls some more… the various "deposit holders" sitting on mountains of dollars have to start pondering their options.

Take the Saudis for example. Their currency, the Saudi riyal, has just hit 21 year highs against the dollar. Should they just sit around and let their greenback pile shrink further? Or should they quietly get a move on?

I think I'll go ahead and panic, thanks

Some believe the dollar can't collapse… that it just wouldn't be rational. The central bankers of the world are too level-headed to dump their holdings en masse.

Question, then--since when are bank runs rational? Would a currency run be so different?

When Continental Illinois depositors withdrew $10 billion in six days in 1984, were they being "rational?" Were the lines… sorry, queues… of Brits snaking around the block to get their money out of Northern Rock "rational?"

Actually it's a trick question. The panicked depositors were being rational in a way. They were acting to save their own skins—in full knowledge that they might not be saved otherwise.

Britain's version of FDIC insurance (bank deposit protection) is nowhere near as generous as America's, and the prospect of having funds locked up for months was very real. If you or I had funds in Northern Rock (or Continental Illinois in 1984), we probably would have cut and run too. It was only when the authorities agreed to fully and unequivocally ride to the rescue that things calmed down.

Of course, there is no FDIC insurance for central banks… no higher authority to turn to when an empire's credit line goes crunch.

Bank runs may not be rational on the whole, but they possess a compelling logic on the ground. When it becomes every man for himself… or every country for itself… collaboration goes right out the window.

If it happened to a British bank for the first time in 141 years, it can happen to the dollar too.

Profitably Yours,

Justice_Litle

http://www.consilientinvestor.com

Copyright © 2007, Angel Publishing LLC and Justice Litle

Justice Litle is the editor and founder of Consilient Investor. Consilient Investor is a broad ranging collection of articles ( written by yours truly) on markets, trading and investing... and big ideas related to such. It is also home to the Consilient Circle, a unique trading and investing service.

Justice_Litle Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.