Should the Fed Pump Even More Money?

Interest-Rates / Quantitative Easing Jul 27, 2010 - 10:50 AM GMTBy: Frank_Shostak

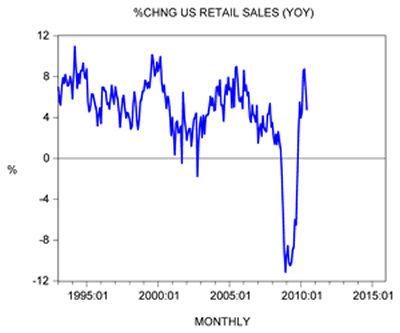

Some Fed officials and various commentators, such as Professor Paul Krugman, are of the view that the US central bank should be ready to consider additional steps to boost the US economy in the wake of a visible softening in key economic data. For instance, the yearly rate of growth of retail sales, after climbing to 8.5% in March, have fallen to 4.8% in June. The ISM manufacturing purchasing manager's index (PMI) fell to 56.2 last month from 59.7 in May.

Some Fed officials and various commentators, such as Professor Paul Krugman, are of the view that the US central bank should be ready to consider additional steps to boost the US economy in the wake of a visible softening in key economic data. For instance, the yearly rate of growth of retail sales, after climbing to 8.5% in March, have fallen to 4.8% in June. The ISM manufacturing purchasing manager's index (PMI) fell to 56.2 last month from 59.7 in May.

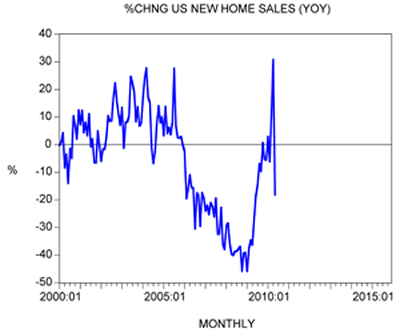

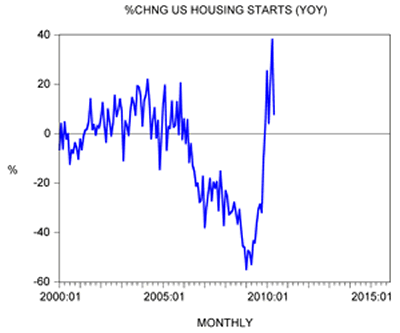

The housing market also shows visible weakening. The growth momentum of new home sales has plunged in May. The yearly rate of growth of sales fell to -18.3% in May from 30.8% in April. The growth momentum of housing starts also displays a visible decline. Year-on-year the rate of growth fell to 7.8% in May from 38.2% in the month before. Furthermore, in the week ending July 9, demand for loans to purchase homes, as depicted by the mortgage purchase index, fell 3.1% to 163.3, the lowest level since December 1996.

In his articles in the New York Times on the June 27 and July 11, professor Paul Krugman warns that without a dramatic fiscal and monetary stimulus the US economy is running the risk of falling into a prolonged depression.

According to Krugman things were different in 2008–2009:

In 2008 and 2009, it seemed as if we might have learned from history. Unlike their predecessors, who raised interest rates in the face of financial crisis, the current leaders of the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank slashed rates and moved to support credit markets. Unlike governments of the past, which tried to balance budgets in the face of a plunging economy, today's governments allowed deficits to rise. And better policies helped the world avoid complete collapse: the recession brought on by the financial crisis arguably ended last summer.[1]

Despite the stimulus, which Krugman labels as good policy, this wasn't sufficient to erase the still-enormous unemployment levels. Hence Krugman's view that more stimulus is required. Unfortunately, argues our New York Times columnist, policy makers are currently moving away from sound policies.

Around the world … Governments are obsessing about inflation when the real threat is deflation, preaching the need for belt-tightening when the real problem is inadequate spending.[2]

Krugman maintains that the current move towards more conservative policies, which he labels as hard-money and balanced-budget orthodoxy, has little to do with rational analysis. According to our professor, this type of thinking will lead to another economic depression and massive unemployment,

And who will pay the price for this triumph of orthodoxy? The answer is, tens of millions of unemployed workers, many of whom will go jobless for years, and some of whom will never work again.[3]

In the face of a weakening in the rate of growth of various price indexes, Krugman holds that the Fed should act swiftly to prevent the economy falling into a deflationary black hole.

Mr. Bernanke's "it" isn't a hypothetical possibility, it's on the verge of happening. And the Fed should be doing all it can to stop it.[4]

Keynesian Ideas Can Only Make Things Much Worse

Following in the footsteps of John Maynard Keynes, most economists — and Krugman in particular — hold that one cannot have complete trust in a market economy, which they see as inherently unstable. If left free, the market economy could self-destruct. Hence there is the need for governments and central banks to manage the economy. In the Keynesian framework, successful management of the economy depends on influencing the overall level of spending. It is spending that generates income. Spending by one individual becomes income for another individual, according to the Keynesian framework.

Hence the more that is spent the better it is going to be. What drives the economy then is spending. If during a recession consumers fail to spend, then it is the role of the government to step in and boost overall spending in order to grow the economy.

In the Keynesian framework of thinking, the output that an economy can generate with a given pool of resources — i.e., labor, tools, and machinery — and a given level of technology, without causing inflation, is labeled "potential output." Hence the greater the pool of resources, all other things being equal, the more output can be generated.

If for whatever reasons the demand for the produced goods is not strong enough, this leads to an economic slump. The inadequate demand for goods leads to only a partial use of existing labor and capital goods.

In this framework then, it makes a lot of sense to boost government spending in order to strengthen demand and eliminate the economic slump.

What is missing in this story is the question of funding. For instance, a baker produces ten loaves of bread and exchanges them for a pair of shoes with a shoemaker. In this example, the baker funds the purchase of the shoes by producing ten loaves of bread.

Note that the bread maintains the shoemaker's life and well-being. Likewise the shoemaker has funded the purchase of bread by means of shoes that maintain the baker's life and well-being.

Now, let us say the baker has decided to build another oven in order to increase the production of bread. In order to implement his plan, the baker hires the services of the oven maker.

He pays the oven maker with some of the bread he is producing. Again what we have here is a set-up where the building of the oven is funded by the production of a final consumer good, bread. If, for whatever reason, the flow of bread production is disrupted, the baker would not be able to pay the oven maker. As a result, the making of the oven would have to be aborted.

From this simple example we can infer that what matters for economic growth is not just the existing stock of tools and machinery and the pool of labor, but an adequate flow of final goods and services that maintain individuals' lives and well-being.

Now, even if we were to accept the Keynesian framework that the potential output is above actual output, it doesn't follow that the increase in government outlays and loose monetary policy will lead to an increase in the economy's actual output.

It is not possible to lift overall production without the necessary support from final goods and services or from the flow of real funding or the flow of real savings. (For instance, out of the production of ten loaves of bread if the baker consumes two loaves, his real saving or real funding is eight loaves.)

We have seen that by means of a final consumer good — the bread — the baker was able to fund the expansion of his production structure.

Similarly, other producers must have saved final real consumer goods — real savings — to fund the purchase of the goods and services they require. Note that the introduction of money doesn't alter the essence of what funding is. Money is just a medium of exchange. It is only used to facilitate the flow of goods, it cannot replace the final consumer goods.

The government as such doesn't create any real wealth, so how can an increase in government outlays revive the economy? Various individuals who are employed by the government expect compensation for their work. The only way it can pay these individuals is by taxing others who are still generating real wealth. By doing this the government weakens the wealth-generating process and undermines prospects for economic recovery. (We ignore here borrowings from foreigners.)

The only way fiscal and monetary stimulus could "work" is if the flow of real savings (i.e., real funding) is large enough to support (i.e., fund) government activities and activities that sprang up on the back of loose-monetary policy while still permitting a positive rate of growth in the activities of real-wealth generators. (Note that the overall increase in real economic activity is in this case erroneously attributed to the loose fiscal and monetary policies.)

If however the flow of real savings is falling, then, regardless of any increase in government outlays and monetary pumping overall, real economic activity cannot be revived. In this case, the more the government spends and the more the central bank pumps, the more will be taken from wealth generators — thereby weakening any prospects for a recovery.

When loose monetary and fiscal policies divert bread from the baker, he will have less bread at his disposal. Consequently the baker will not be able to secure the services of the oven maker. As a result, it will not be possible to boost the production of bread, all other things being equal.

As the pace of loose policies intensifies, a situation could emerge whereby the baker will not have enough bread to even maintain the workability of the existing oven. (For instance, the baker might not have enough bread to pay for the services of a technician to maintain the existing oven in good shape.) Consequently, his production of bread will actually decline.

Similarly, other wealth generators, as a result of the increase in government outlays and monetary pumping, will have less real funding at their disposal. This in turn will hamper the production of their goods and services and will retard — not promote — overall real economic growth.

As one can see, not only does the increase in loose fiscal and monetary policies fail to raise overall output, but on the contrary it leads to a weakening in the process of wealth generation in general. According to Ludwig von Mises,

there is need to emphasize the truism that a government can spend or invest only what it takes away from its citizens and that its additional spending and investment curtails the citizens' spending and investment to the full extent of its quantity. [5]

Money Supply and Economic Indicators

The so-called economic recovery, which Krugman and most commentators attribute to the success of loose fiscal and monetary policies during 2008–2009, is just a reflection of monetary pumping by the Fed.

Year on year, the rate of growth of the Fed's balance sheet (monetary pumping) climbed to 152.8% in December 2008 from 1.5% in February 2008. The pace of pumping remained very high during 2009, hovering at 125% from January to September. As a result, the yearly rate of growth of our monetary measure for the United States jumped to almost 33% in November 2008. From December 2008 to September 2009, the yearly rate of growth of AMS hovered at around 22%.

Since most economic indicators reflect monetary expenditure, obviously the stronger the monetary pumping is, the stronger most economic indicators become. This of course means that the expansion of various economic indicators reflects a weakening in the process of real-wealth formation. Yet most commentators, including Krugman, label monetary-driven expansion a good thing. (Note that this expansion is labeled "economic recovery.")

From this we can infer that a decline in the pace of pumping since September last year is behind the current decline of the rate of growth in various economic indicators. The decline in the rate of expansion slows down the rate of damage to the process of real-wealth formation. Hence the slowdown in the expansion should be regarded as good news for the economy. (Note that there is a variable time lag between changes in the monetary expansion and changes in various economic indicators.) The yearly rate of growth of Fed's balance sheet and AMS stood at 13.7% and 2.3% respectively in June.

Obviously the Fed can accelerate the pace of pumping by embarking on a very aggressive buying of assets. This pumped money, however, is unlikely to enter the economy as long as commercial-bank lending remains depressed. (We ignore the case of the Fed buying assets directly from nonbanks.) Now, even if pumped money enters the economy, it will only undermine further the process of real-wealth formation and make the already bad economic environment much worse.

The fact that banks are reluctant to go full ahead with the expansion of credit is indicative that the pool of real savings is in trouble; after all, the essence of credit is the lending of real savings. Lending is a transfer of real savings from a lender to a borrower by means of the medium of exchange, i.e., money.

The existence of banks enhances the use of real savings. By fulfilling the role of middleman, banks make it easier for a lender to find a borrower. When a bank lends money, it in fact provides the borrower with the medium of exchange that can be employed to secure the real stuff that is required to maintain people's lives and well-beings.

It is therefore futile to urge banks (as various commentators including Bernanke and Krugman are doing) to lend more if real savings are not there. If the banks are forced to expand lending while the pool of real savings is declining, this would mean that they have to expand credit "out of thin air." Needless to say, inflationary credit can only make things much worse.

Why Economic Cleansing Promotes Economic Growth

The conventional thinking headed by Krugman presents economic adjustment — "economic recession" — as something terrible, even the end of the world. In fact, economic adjustment is not menacing or terrible; from an economic point of view, it is nothing more than a time when scarce resources are reallocated in accordance with consumers' priorities.

Allowing the market to do the allocation always leads to better results. Even the founder of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Lenin, understood this when he introduced the market mechanism for a brief period in March 1921 to restore the supply of goods and prevent economic catastrophe. Yet for some strange reason, most experts these days cling to the view that the market cannot be trusted in difficult times.

If central bankers and government bureaucrats can fix things in difficult times, why not in good times too? Why not have a fully controlled economy to fix all the problems forever? The collapse of the Soviet Union's centralized system is the best testimony one can have that controls don't work. A better way to fix economic problems is to allow entrepreneurs the freedom to allocate resources in accordance with people's priorities. In this sense, the best stimulus plan is to allow the market mechanism to operate freely. Allowing the market to do the job will result in some activities disappearing altogether, and other activities in fact expanding.

Take, for instance, a company that has six profitable activities and four losing activities. The management of the company concludes that the four losing activities must go. To keep them alive is a threat to the survival of the company; these activities rob scarce funding from profitable activities. Once the losing activities are shut down, the released funding can now be employed to strengthen the winning activities. The management can also decide to use some of the released funding to acquire some other profitable activities. This is precisely what the government and central-bank stimulus policies prevent from happening.

Loose fiscal and monetary policies are not going to rescue the economy; they will only rescue activities that the economy cannot afford and that consumers do not want. These policies will sustain waste and promote inefficiency, draining resources from growth and efficiency. Remember: government is not a wealth generator; it can only take resources from A and give them to B.

Why Doing Nothing Is the Best Policy to Revive the Economy

Contrary to Krugman and other commentators, we suggest that the best economic policy for the Fed and the government is to do nothing as soon as possible. By doing nothing, the Fed will enable wealth generators to accumulate real savings. The policy of doing nothing will force those activities that add nothing to the pool of real savings to disappear. This will make the life of wealth generators much easier. As time goes by, the expanding pool of real savings will set a platform for the further expansion of various wealth-generating activities. So the sooner the Fed and the government stop tampering, the sooner an economic recovery will emerge.

We suggest that decades of reckless monetary and fiscal policies have severely depleted the pool of real savings. So, again, more of the loose policies cannot make the current situation better. On the contrary, such policies only further delay the economic recovery. Hence, contrary to Krugman, we can suggest that a move toward greater conservatism is a step in the right direction.

Also contrary to Krugman, the unemployment rate could be lowered rather quickly if the labor market were freed. What is required, however, is not the lowering of unemployment as such but the creation of an environment where individuals can earn incomes that will enable them to lift their living standards. The key for such an environment is to stop sabotaging the process of real-wealth generation by means of loose policies.

Conclusion

Contrary to Krugman and other mainstream economists, neither the Fed nor the government's loose monetary and fiscal policies can cause an expansion in the pool of real savings. In fact, loose policies only weaken the process of real-wealth formation, thereby weakening prospects for a sustained economic expansion.

If loose monetary and fiscal policies could have been instrumental for economic growth, then by now all the poverty in the world would have been eradicated. The only reason why loose monetary and fiscal policies have ever appeared to be effective is because the pool of real savings was expanding. However, once this pool becomes stagnant or declining, the illusion of the effectiveness of loose monetary and fiscal policies is shattered. The more aggressive the fiscal- and monetary-policy stance is, the worse the economic conditions become.

Now, if the pool of real savings is still OK, then there is no need for Krugman's policies to revive the economy — the pool will do it. If the pool is in trouble, Krugman's policies will only make things much worse, and we could end up in a prolonged economic depression. The best policy is to do nothing.

Notes

[1] Paul Krugman, "The Third Depression," New York Times, June 27, 2010.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Paul Krugman, "The Feckless Fed," New York Times, July 11, 2010.

[5] Ludwig von Mises, Human Action 3rd revised edition p. 744.

Frank Shostak is an adjunct scholar of the Mises Institute and a frequent contributor to Mises.org. He is chief economist of M.F. Global. Send him mail. See his article archives. Comment on the blog.![]()

© 2010 Copyright Ludwig von Mises - All Rights Reserved Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.