Stock Market Stuck as Investors Demand Risk Premium for Buying

Stock-Markets / Stock Markets 2010 Jun 14, 2010 - 05:56 AM GMTBy: Money_Morning

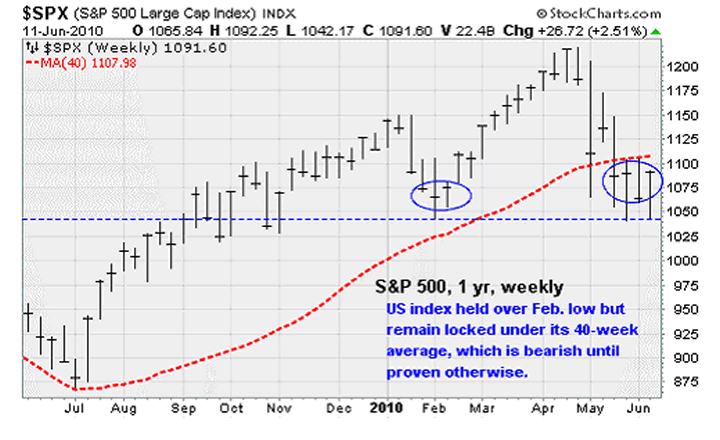

Jon D. Markman writes: Stocks rose worldwide over the past week by 2% to 5%, swelling with sudden courage after positive economic reports from China and shaking off some worsening news in the United States about retail sales and jobs.

Jon D. Markman writes: Stocks rose worldwide over the past week by 2% to 5%, swelling with sudden courage after positive economic reports from China and shaking off some worsening news in the United States about retail sales and jobs.

Yet results in the past month are still heavily negative, ranging from -5.5% for U.S. stocks and -8.5% for Europe. China has suddenly become the most buoyant region, up 1.5% in the past month.

The variation in one-week and one-month results illustrate perfectly how investors are showing that they are hopeful but unconvinced that recent strength in GDP growth and corporate income advances are sustainable, and therefore won't buy stocks heavily until prices are so cheap that they discount worst-case scenarios. They want a high risk premium, in other words, before buying -- sort of like demanding a 72-month warranty before buying an expensive car.

This is a problem because the risk argument is not easily refutable. Most of the threat is coming from Europe, so there is very little that U.S. policymakers or corporate leaders can do or say to allay the fears. Meanwhile, policy makers, regulators and bankers in the capital-rich countries of Germany, France and the UK are about as coordinated as the raindrops in a hurricane. We may be waiting in vain for them to give a credible, united all-clear signal.

Two types of events can turn around a condition like this: a) Prices get so low that they discount even the worst-case scenarios and greed-mad buyers cannot help but buy stocks; or b) policymakers take credible steps to allay fears that are acting like paralyzing rays from a stun gun.

In March 2009, both happened. Stocks were already super-cheap when the turnaround came, but the spark of upside ignition came when the world's government leaders and central bankers all said that they would begin working together to guarantee big financial companies' loans and stimulate spending, and the United States launched the campaign to "stress-test" the banks' balance sheets.

Now we have a more grave situation, unfortunately. U.S. officials have eroded the credibility they won last year with repetitive missteps, and European officials have done nothing to show the world that they will work together to guarantee loans, with German and UK policymakers in particular at each others' throats. And worse, this time the debts are far larger than the ones we fretted about in 2009 because they are on the balance sheets of both banks and governments.

Credit analyst Satyajit Das told us three weeks ago that there's just not enough money to repay all Europe and U.S. debts, and we are beginning to see the wisdom of that view. After you've already spent more than $1 trillion moving private debt to the public books, how do you come up with another $1 trillion to move them off the public books?

Das said maybe Martians could show up to move the debt onto intergalactic balance sheets, but I doubt even Siths or Jedis are interested in helping.

The longer that risks from European credit troubles are allowed to fester the longer the intermediate-term downturn will hem in sporadic short-term bursts of optimism. Absent new data that allays the fears and encourages investors to chill out, the beatings will continue until morale improves.

Fed Model Shows Stocks Undervalued

By a lot of old-fashioned valuation metrics, stocks are an absolute screaming buy. That's because the recent decline has not been a reaction to prices that are perceived to be too high but to risks that are perceived to be too high. It's almost as if investors just can't get the images of the 2008-2009 decline out of their heads. It's like accident victims that cringe at the sound of any skidding car.

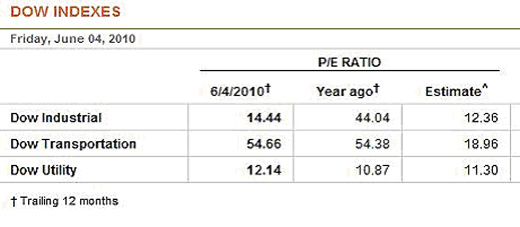

A common valuation model for stocks is called the Fed model. Developed at the Federal Reserve and widely taught in business schools, it argues that the U.S. market is fairly valued when the earnings yield of Dow Jones Industrials companies' earnings in the following year are equal to the yield of a 10-year Treasury note. This is because stocks and bonds are considered to be alternatives. If one is cheaper than the other, then it is expected to get the bulk of future investment.

Dust off your old valuation handbooks and you'll find that the earnings yield is the inverse of the price/earnings ratio, expressed as a percent. For the Dow Jones Industrials, the forward P/E is 12.36, while the P/E on trailing 12-month earnings is 14.4. If you have a Wall Street Journal online subscription, you can view the table above at this page in the Market Data Center.

Divide 1 by 12.36 and you get 8.09%. Divide 1 by 14.4 and you get 6.9%. Compare those to a 10-year yield of 3.2% and you can see that under the Fed model, the Dow should be more than twice as high, at 24,800, while the S&P 500 Index should be around 2,600.

Even if the forward estimates are too high by half, the indexes should still be at least 50% higher than their present values, according to this simple model that has proven to be a valuable guide for many years. The bottom line is that, at present, the expected return of U.S. stocks should be seen as so much higher than the expected return on bonds that they should attract investors by the droves.

So why are stocks stuck? It's the risk premium, which centers now on both European credit risk and Chinese banking system fears. Investors simply seem to believe that the risk of credit contagion from Europe and Asia infecting the United States is so great that they won't buy until prices discount worst-case scenarios.

This is more than a little odd because U.S. bond traders themselves -- who know the most about credit -- are not nearly as concerned. Bond prices have softened a touch in the United States but they are not nearly as bad as they were last time that stocks fell off a cliff. High-yield bonds are a bit off their highs, but nothing outrageous like the late summer of 2008.

Credit analyst Brian Reynolds is telling clients that he thinks the current correction still has a ways to go because bears are banging on derivative products in a way that makes equity investors think that things are a lot worse than they really are. Perceptions can become a kind of reality in the world of securities until enough time goes by that investors realize they are unfounded.

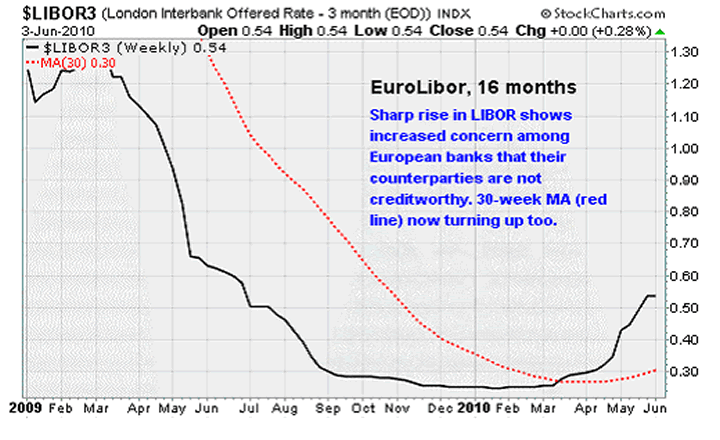

The real problem, though, is that credit really is in bad shape in Europe, as evidenced by the rising Euro-Libor rate, shown above. This is the rate that European banks charge each other for loans. When they are worried they might not get paid back on time, the rate goes up. It's currently at very low levels from a historical perspective because rates everywhere are depressed, but it's way up from late last year.

The Libor and European bond markets are saying that German, French, British, Spanish, Austrian and Belgian banks really are in the soup when it comes to their loans, as they were never stress-tested in 2009 like U.S. banks and are known to be carrying much more toxic assets on their balance sheets. A New York Times article titled, "Debtors Prism" this month argued that there is $2.6 trillion in sovereign and corporate debt issued by Greece, Spain and Portugal alone, and no complete accounting of which European banks own it and how much of it is at risk.

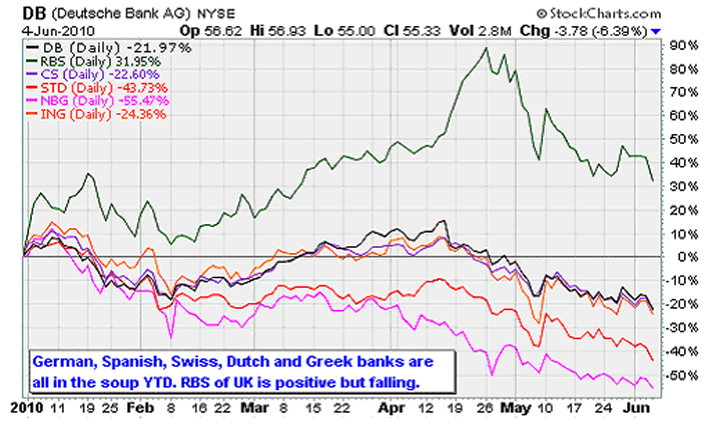

Transparency is almost non-existent, but you can bet that the majority of it is owned by the usual suspects: Deutsche Bank AG (NYSE: DB), Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (NYSE ADR: RBS), ING Groep N.V. (NYSE ADR: ING), Banco Santander SA (NYSE ADR: STD), HSBC Holdings plc (NYSE ADR: HBC), Credit Suisse Group AG (NYSE ADR: CS), UBS AG (NYSE: UBS), Lloyds Banking Group plc (NYSE ADR: LYG) and Barclays plc (NYSE ADR: BCS).

It's kind of amazing that even after all this time the corrosion of European banks' underlying structure from the mid-2000s lending debacle is still not fully understood. Now add the new concerns over sovereign debt to the lingering 2008-vintage fears over commercial debt, and you can see why the Continent is cracking.

The bottom line is that while U.S. regulators like the Fed and SEC, as faulty as they are, teamed up effectively to root out the bulk of the problems at American banks and expose them to the light, the same has not been done in Europe -- and that has put Continental economies in peril.

So while U.S. growth is probably sufficient to support a rising stock market at this time, the same cannot be said with conviction about Europe. And until Europe gets its act together, U.S. banks and corporations will suffer from guilt by association -- and thus their shares will be weighed down by a heavy risk premium.

One More Minute on Europe

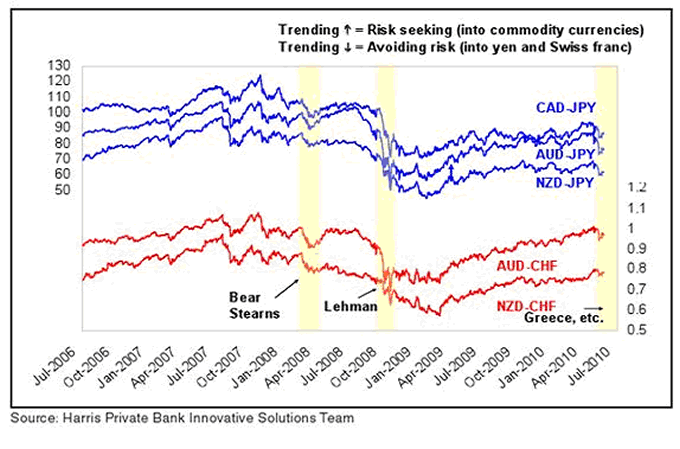

BMO Capital Markets analysts report that the rule of thumb for the last three years has been to look out below any time the yen, Swiss franc or US dollar was trending higher. So make no mistake: the attack on the euro currency has eroded the ''risk on'' commodity currencies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand -- crushing their values in a way that last occurred amid the demise of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.

The chart above which depicts this phenomenon is fascinating, though it may take awhile to understand. The top three blue lines are, in order, the Canada Dollar / Japanese Yen pair; the Aussie Dollar / Yen pair; and the New Zealand Dollar / Yen pair. The bottom red lines are Aussie Dollar / Swiss Franc and New Zealand Dollar / Swiss Franc.

When investors wish to take risk via a "carry trade," they buy the high-yielding Canadian, Aussie and Kiwi dollar and sell low-yielding yen. When they wish to avoid risk and reverse the carry trade, they sell the Aussie and Kiwi dollar and buy Swiss francs. At present, you can see that the "risk-off" trade now dominates because the blue lines are starting to trend higher and the red lines are falling.

BMO analysts add that although many economic indicators coming from the European Union are fine, there is growing realization that GDP growth on the Continent will stall out. Year-over-year registrations for new cars, for example, were able to rebound to +27.5% back in November 2009, but the figure has been unwinding ever since. Auto sales are now down 10.2% from this time last year, indicating that Europe is having difficulty growing the economic data now that the comparable figures of last year are no longer at depression levels.

A worsening economy in Europe at a time when U.S. conditions are relatively steady is bullish for the dollar and thus bearish for the carry trade. That in turn is deflationary, and thus bearish for stocks. It's all connected.

Week in review

Monday: No major economic releases.

Tuesday: The NFIB Small Business Optimism Index increased to 92.2 for May from 90.6 previously -- the best reading since Lehman Bros. imploded back in September 2008. Still, it wasn't all sunshine and lollipops: The important index components for job creation and capital expenditures plans remained at recession levels.

Wednesday: The Federal Reserve's Beige Book report stated that economic activity continued to improve in all twelve Fed districts. Consumer spending was singled out as a particular area of strength compared to April's report.

Thursday: Initial weekly jobless claims remained troublingly high at 456,000 versus expectations for 448,000. The four-week moving average for claims increased for the fourth straight week to the highest level in three months. If we don't see progress on this front soon, there'll be real trouble.

Friday: The consumer was the center of attention today after May retail sales came in well under expectations. Sales fell 1.2% for the month, led by a decline in building materials and garden supplies, versus the 0.4% expansion analysts were expecting. The negative news was tempered somewhat by word that consumer confidence strengthened to the best levels since early 2008. Also, it's worth keeping in mind that retail sales are up 5.7% since the recession unofficially ended last June. Deutsche Bank economist Joseph LaVorgna notes that given the pact of improvement in jobless claims (-24% year over year), consumer spending should hold up nicely in the coming quarters.

The week ahead

Monday: No major economic releases.

Tuesday: The Empire State Manufacturing Survey will provide an update of manufacturing activity in the state of New York.

Wednesday: Reports on housing starts, inflation via the Producer Price Index, and industrial production.

Thursday: Another read on inflation courtesy of the Consumer Price Index. Also, the latest economic leading indicators will be released.

Friday: No major economic releases, but it is a quadruple witching session as options and futures for June expire.

[Editor's Note: As this market analysis demonstrates, Money Morning Contributing Writer Jon D. Markman has a unique view of both the world economy and the global financial markets. With uncertainty the watchword and volatility the norm in today's markets, low-risk/high-profit investments will be tougher than ever to find.

It will take a seasoned guide to uncover those opportunities.

Markman is that guide.

In the face of what's been the toughest market for investors since the Great Depression, it's time to sweep away the uncertainty and eradicate the worry. That's why investors subscribe to Markman's Strategic Advantage newsletter every week: He can see opportunity when other investors are blinded by worry.

Subscribe to Strategic Advantage and hire Markman to be your guide. For more information, please click here.]

Source: http://moneymorning.com/2010/06/14/stock-market-risk-premium/

Money Morning/The Money Map Report

©2010 Monument Street Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Protected by copyright laws of the United States and international treaties. Any reproduction, copying, or redistribution (electronic or otherwise, including on the world wide web), of content from this website, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of Monument Street Publishing. 105 West Monument Street, Baltimore MD 21201, Email: customerservice@moneymorning.com

Disclaimer: Nothing published by Money Morning should be considered personalized investment advice. Although our employees may answer your general customer service questions, they are not licensed under securities laws to address your particular investment situation. No communication by our employees to you should be deemed as personalized investent advice. We expressly forbid our writers from having a financial interest in any security recommended to our readers. All of our employees and agents must wait 24 hours after on-line publication, or 72 hours after the mailing of printed-only publication prior to following an initial recommendation. Any investments recommended by Money Morning should be made only after consulting with your investment advisor and only after reviewing the prospectus or financial statements of the company.

Money Morning Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.