The Current Financial Crisis — and After

Economics / Credit Crisis 2010 Apr 09, 2010 - 02:22 AM GMTBy: MISES

Kevin Dowd writes: My main topic this morning is the resolution of the current financial crisis, and what might be done to fix the financial system and help avert another crisis in the future.

Kevin Dowd writes: My main topic this morning is the resolution of the current financial crisis, and what might be done to fix the financial system and help avert another crisis in the future.

If this sounds like good news, it is indeed. But you should beware of economists bearing good news on a beautiful Sunday morning: economics isn't known as the dismal science for nothing.

There is also the bad news — and then there is the very bad news.

There is also the bad news — and then there is the very bad news.

The bad news is that the authorities badly botched it, at massive cost to us all — except to the bankers, of course, who are laughing all the way to what is left of our banks. And we are not out of the woods yet, by any means, and the authorities' responses to the crisis are already sowing the seeds of a new, probably worse crisis down the road.

That is pretty bad, to be sure, but that's only a preamble to the very bad news. The really bad news is that, even if we get through our current problems in half-decent shape, there are some disturbing storm clouds on the horizon, and these are much more ominous than the current crisis itself.

Keynesian Economics

The first thing to appreciate is the power of ideas. And one point that this crisis has conclusively demonstrated is the enduring hold of Keynesian economics. People now forget that Keynesianism didn't work well, even in the 1930s; its short-term focus and its failure to deal with the monetary side of the economy led to inflation and, ultimately, to the miseries of stagflation in the '70s. Keynesianism's failure was then manifest, and it was rightly repudiated. Fiscal and monetary extravagance were then reined in, inflation was painfully brought down, and the economy boomed.

And then comes the next big crisis, and Keynesianism is suddenly respectable again —and back with a vengeance. We are now told that Keynesian solutions are the only solutions. And it's not just Keynesianism, but Keynesianism on a mass (or should I say, crass?) scale: massive fiscal stimulus, regardless of the cost; and loose monetary policy, regardless of the inflationary dangers.

This reminds me of an old joke: Keynes was once giving a lecture and noticed that one of his students had fallen asleep. So Keynes asked him a direct question, which woke him up. The startled student responded: "I'm sorry, Mr. Keynes, I didn't hear the question. But the answer is that we need more stimulus."

One size fits all, basically.

We have been here before. Writing in 1940, Friedrich Hayek gave perhaps the most perceptive critique of Keynesian economics ever mounted:

I cannot help regarding the increasing concentration on short-run effects … not only as a serious and dangerous intellectual error, but as a betrayal of the main duty of the economist and a grave menace to our civilisation.…

It is alarming to see that after we have once gone through the process of developing a systematic account of those forces which in the long run determine prices and production, we are now called upon to scrap it, in order to replace it by the short-sighted philosophy of the business man raised to the dignity of a science. Are we not told that, "since in the long run we are all dead," policy should be guided entirely by short-run considerations? I fear that these believers in the principle of après nous le déluge may get what they have bargained for sooner than they wish.[1]

Then, as now, a spending orgy is not what we need. What is needed is a considered response that addresses the structural problems ailing the economy. The key issue, in essence, is that the economy's financial engine has broken down, and this engine needs to be repaired before the economy can properly recover.

Resolving the Financial Crisis

So how do we fix the financial engine? The answer is that we need to restructure the balance sheets of the main financial institutions. And, as we all know, these balance sheets are best understood using the medium of — poetry:

A balance sheet has two sides.

A right-hand side and a left-hand side.

On the right, nothing is left.

And on the left, nothing is right.

Believe it or not, this little poem gives us the key to resolving the financial crisis. So let's have a look at a balance sheet:

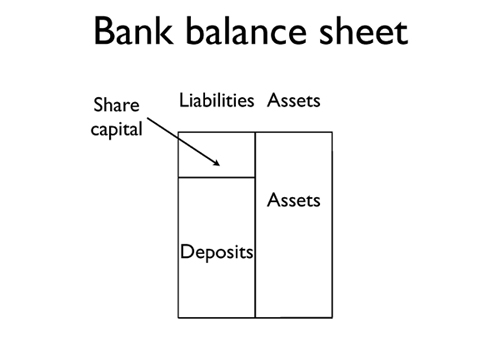

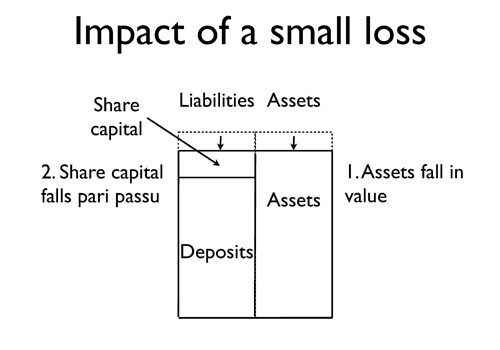

The right-hand side shows the bank's assets, which move up and down in value depending on whether the bank makes profits or losses. The left-hand side shows the claims on those assets, the liabilities. These liabilities consist of the bank's deposits and its share capital. This share capital is also a buffer that protects the value of the deposits and reassures depositors that their money is safe. So, for example, if the bank takes a loss, the loss is usually borne by the shareholders, but if the buffer is big enough, then the bank can absorb any reasonable loss and still have enough share capital left to be safe. This situation is illustrated in the next slide:

The bank makes a small loss, but can absorb it and still be safe.

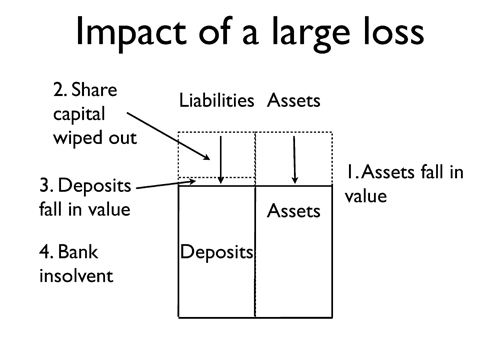

However, if the bank takes a very big loss, we get the following situation:

The bank's loss is now so high that the value of the bank's assets is not enough to pay off the depositors in full. In this case, the shareholders are wiped out completely, and depositors take a loss too. The bank is now insolvent — it can't meet its debts.

The problem now is how to get the bank back on its feet and operating again on a solvent, going-concern basis.

The answer is to rebuild the banks' balance sheets. There are good and bad ways of doing this.

The authorities chose the bad way. They panicked — what else could we have expected? And in their panic they injected massive amounts of taxpayer money into the banks, and in so doing threw our money into a virtually bottomless hole.

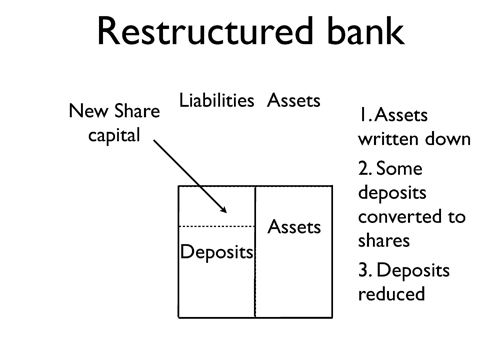

A much better way, by contrast, is to rebuild the banks' balance sheets following the precedents of traditional bankruptcy law. The bank would go into some form of temporary receivership, and three things would happen:

1. Its assets would be marked down in value to reflect the losses.

2. The liabilities would be marked down by the same amount.

3. The liabilities would be reorganized so that the bank would have a decent capital base again. This new share capital would come from the depositors, some of whose deposits would be converted into shares.

We might also wish to ring fence the smaller depositors to protect them — this would make the package easier to sell politically, but this is a detail.

The restructuring is shown in the next slide:

The bank's balance sheet is now much smaller, but the new capital base is large enough to make the bank safe again. The bank can then return to normal business but on a smaller scale.

There would be no taxpayer bailout, no propping up weak institutions, no too-big-to-fail, no humoring of the banks and their bonus culture, no prolonged period of crippling uncertainty, no fiscal profligacy, no loose money. Instead, we should have a quick, emergency-room operation on the economy's financial engine followed by a rapid return to normal market conditions. This is rather different from what actually happened.

Of course, I am not suggesting that the operation would be easy. In particular, it is very difficult to work out what the "true" value of the banks' assets should be — no one really knows what a toxic asset is worth. But fortunately, it is not necessary for the write-downs to be "realistic" or accurate. In fact, it is best if the write-downs are harsh and the valuations biased on the conservative side, and these could be based on formulas reflecting worst-case estimates of what different types of asset might be worth (i.e., zero in some cases). And if those valuations later turn out to be too low, it doesn't really matter: the banks' assets can be marked up again later.

The trick in all this is speed. We could close down the banks or limit their operations for a weekend or a few days, but not for months. A prolonged disruption of bank activities would cripple the payments system and the supply of credit to the broader economy, and this would be catastrophic. It is therefore essential that the operation be carried out quickly to minimize the disruption to bank activities — and not for the sake of the banks, but for the sake of everyone else.

Looking forward, we should be looking at a reform package with a number of key elements:

First, we should consider reforms of bankruptcy and insolvency laws to get the ER treatment "right" in the future: should any bank ever need emergency surgery again, this should be a straightforward, by-the-book process anticipated and thought through in advance, not some battlefield-surgery hatchet job.

Second, the financial-services industry needs serious reform. Hard to believe as it might be, there was once a time when the industry was conservative and respected, when it focused on providing straightforward financial "products" to its customers and did so well. We have got to get back to that. No more financial hydrogen bombs blowing up the financial system.

The key to this is corporate-governance reform. I am talking, not about tinkering with the number of nonexecutive directors or a new Sarbanes-Oxley, but radical reform to make the banks accountable and to rein in the moral hazards that have run rampant. And the key to good corporate governance is to remove limited liability: we should abolish the limited-liability statutes and give the bankers the strongest possible incentives to look after our money properly.

And, of course, there is our old enemy, the state. If I had my way, the state would be rolled back right: no deposit insurance, no capital adequacy rules, no financial regulation, no central bank, no monetary policy — in short, the restoration of a sound monetary standard.

Short- and Medium-Term Economic Prospects

I could easily spend the rest of my talk drooling over these wish-lists. But rather than do that, I would like to spend the rest of my time looking at our economic prospects. And our prospects are not too good. To save time, I will focus on the US, but much of what I say applies to some extent to other countries too.

Let's start with inflation.

If we look over the period 2006–2008, we see inflation of between 2% and 4% on a year-on-year basis, and the broader monetary aggregates expanding quite rapidly and growing at double-digit rates by the end of 2008. We also see an extraordinary growth in the narrowest aggregate, the monetary base, which grew 100% over 2008, a consequence of the highly dangerous and irresponsible policy of "quantitative easing."

From early this year, admittedly, we see monetary growth halting and prices falling a little. However, I wouldn't put too much emphasis in such a short downturn in the monetary growth rates, especially in a period where the demand for money is clearly falling due to the impact of the recession. Instead, we need to look over the broad period and consider the likely impact of the large amount of excess money that is already in the system. So, overall, combined with still-low interest rates, these figures indicate a loose monetary policy and the prospect of resurgent inflation once economic activity returns to normal.

Interest rates are low, due in part to "soft" monetary policy, but also due to a flood of hot money pouring into the allegedly safe US Treasury bond market. Low interest rates mean high bond prices, and there are signs that the T-bill market is undergoing a fair-sized speculative bubble. This bubble would seem to be very vulnerable — even a small rise in inflation could easily trigger a loss of confidence and a massive exit from the market. If that happens, market interest rates could rise sharply. And of course, we shouldn't forget that the prospect of massive federal deficits for years to come will also put upward pressure on interest rates. So interest rates are set to rise.

At the same time, the Fed faces a difficult dilemma: If it continues with its current monetary policy, then inflation will return, and probably with a vengeance. The worst thing that the Fed can then do is to put its foot down even harder on the monetary accelerator. This would push interest rates back down temporarily but lead to higher inflation and higher interest rates down the road — and, in all likelihood, to the return of stagflation and yet another massive boom–bust cycle.

But on the other hand, the best thing that the Fed can do is also the hardest thing for it to do: bite the bullet and put its foot on the monetary brakes. Such a policy would encounter massive political resistance — and risk pricking the bond-market bubble and stalling the nascent economic recovery.

In effect, the Fed now risks being hoist by its own petard, a consequence of its own past profligacy.

So the near-term outlook is not too good: the prospect of renewed inflation, even hyperinflation; higher interests rates; a bond-market crash; an uncertain and possibly stalled economic recovery; and the danger of a dollar crisis.

And for those of you who want any investment advice, my advice boils down to a choice between two positions: a cash position and a fetal one.

Long-Term Prospects: Deficits + Entitlements

But all these shorter-term worries pale compared to the long-term outlook.

Federal deficits will be more than 10% of GDP for years to come — these are extremely high.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. We also have to take account of the unfunded entitlements to which the federal government has committed itself: Medicare and Medicaid entitlements; and pay-as-you-go funding of Social Security, that is, state pensions paid for through current tax revenue, not funded in advance.

These are set to grow massively due to there being more retirees relative to workers, retirees being set to live longer, and old-age entitlements growing higher.

Let's look at some figures:

The cost of unfunded Social Security and Medicaid is over $100 trillion — and rising. This is about ten times bigger than the total existing debt of the United States, and it is about $330,000 per man, woman and child in the United States — or about $1.3m for a family of four. And rising.

So your average US family of four is facing a government-imposed bill of $1.3m on top of existing taxes! Change the sign around and they'd all be millionaires! Welcome to the age of the negative millionaire.

It is not surprising, then, that leading experts are now openly asking if the United States is bankrupt, and they are anticipating possible futures in which young, educated Americans flee the country in large numbers to escape crippling taxes — and, of course, in so doing, leave their fellow citizens with even greater per capita burdens to bear. A real case of "last one to leave please switch off the lights."

To quote one leading authority, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas:

I see a frightful storm brewing in the form of untethered government debt.… Unless we take steps to deal with it, the long-term fiscal situation of the federal government will be unimaginably more devastating to our economic prosperity than the subprime debacle and the recent debauching of credit markets. (Richard W. Fisher, 2008)[2]

For those of you who are young, the implications are personal. You have your college debts to pay off. It's hard to get a job, let alone a well-paying one. You can't get on the housing ladder because property is too expensive. Taxes are likely to be high and rising throughout your working life.

You won't have much left to pay for your own personal pension. And yet current projections suggest that you are likely to live well into your 90s or later, and there will be little left in the kitty for your state pension when you retire — assuming that you can retire at all. Pension experts are now talking about the end of retirement, and retirement ages are already starting to rise.

Historically speaking, a good retirement will be seen in the future as a 20th-century luxury, something that people before or since usually didn't get. And you came too late: whereas earlier generations had it easy, you can look forward to busting your gut all your life and working till you drop.

If you are not thoroughly depressed by now, then I am obviously not getting my message across.

You might object that this nightmare scenario is an unfair rip-off, and you would be quite right. Indeed, it might remind some of you of a Ponzi (or pyramid) scheme. A Ponzi scheme is essentially a scam. Someone sets up an investment scheme and gets other people to put their money into it. These people draw in others, and they in turn draw in more people, and so on. Each new intake imagines that their money is being invested on their behalf, but in reality the money is being creamed off by those already in the system.

The process continues for as long as enough new suckers come in, but at some point it becomes clear that the scheme cannot pay out. The supply of suckers then dries up and the scheme collapses. And collapse is inevitable. Those who come in early do well, those who come later do badly — and those who come in last lose everything.

I would suggest that the pensions/social security system — the system of intergenerational transfers in which the young get signed up by their elders, often before they are born — not only resembles but actually is an intergenerational Ponzi scheme, the biggest scam ever invented. And to you young people here, I am sorry to say, if you want to see who the suckers of this Ponzi scheme are, just look in the mirror.

So the system must inevitably collapse. The younger you are, the more you stand to lose. And the longer the scam goes on, the more it will cost you.

To you youngsters, I say: it's your choice how long you choose to put up with this. I say it's your choice because — with a bit of luck — those of us who are older will have departed the scene when these particular chickens come home to roost.

It's your choice.

You can play by the rules your elders would impose on you. You can expect to pay higher and higher taxes, work harder and harder to stand still, and get less and less back in return for yourselves — a life little different from slavery — and then the system will collapse anyway.

Or, alternatively, you can fight back. There is no law of nature that says you have to honor checks that other people write at your expense. You are not slaves — you are slaves only if you choose to submit to slavery. You can repudiate those checks.

I am very aware that we are in unchartered territory here, and the implications of what I am saying are revolutionary and certainly dangerous.

Let's be blunt about what I am suggesting. I am suggesting that if default is inevitable, and if default is more damaging the longer it is delayed, then it would be a good idea to consider embracing it. We should lance the boil, as it were, and kill off the scam — sooner rather than later.

Do you want a life of toil and slavery, followed by ultimate destitution, or do you want to stand up for yourselves and fight for the chance of a decent life? It's your choice.

Who was it that once told the workers of the world that they had nothing to lose but their chains?

I would like to end as I started, with the man of the moment, the prophet of the short-term, John Maynard Keynes. In 1930, Keynes wrote a delightful essay, "Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren," in which he peered into his crystal ball and mused about how economic life would be a hundred years hence, in 2030, now only a couple of decades away.[3]

Keynes anticipated the benefits of technological progress taking us gradually toward a state of economic bliss in which the problem of economic necessity would in essence be solved. He anticipated three-hour shifts and fifteen-hour working weeks, worked not so much out of need, but more for the sake of having something to do, and he worried about how people would mentally adjust to having so much spare time on their hands. We would be like the Biblical lilies of the field, who neither toil nor spin.

And, at long last, after millennia of struggle, real life would finally catch up with the traditional charwoman's epitaph. After a lifetime of unrelenting hard work, she went to her grave looking forward above all else to a very, very long rest:

Don't mourn for me, friends, don't weep for me never,

For I'm going to do nothing for ever and ever.

At least Keynes was right about one thing: all that spare leisure time is overrated. Thank you all.

Notes

[1] Friedrich A. Hayek, The Pure Theory of Capital, Chicago University Press, 1941, pp. 409–410.

[2] Richard W. Fisher, "Storms on the Horizon," Remarks before the Commonwealth Club of California. San Francisco, California, May 28, 2008.

[3] John Maynard Keynes, "Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren," reprinted in Essays in Persuasion, W.W. Norton reprint, 1963.

Kevin Dowd is a lifelong libertarian economist whose main work has been on free banking and financial laissez-faire. He has recently retired from the University of Nottingham in England and lives in Sheffield, England, with his wife and their two daughters. His next book (written with Martin Hutchinson), Alchemists of Loss: How Modern Finance and Government Intervention Crashed the Financial System, is due to be published by Wiley in May. See Kevin Dowd's article archives. Comment on the blog.![]()

This talk was first presented at the Paris Freedom Fest, September 13, 2009.

© 2010 Copyright Kevin Dowd - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.