The FED Won't Deflate or Even Seriously Disinflate

Economics / Inflation Mar 07, 2010 - 04:35 PM GMTBy: Michael_S_Rozeff

The FED, in my opinion, is a price taker in the security markets. While its control over the interest rate in the inter-bank market for reserves (Federal Funds) may be very large in the short run, it cannot and does not control interest rates in other markets, such as Treasury bills. These rates and yields are linked to world markets that are too large for the FED to control.

The FED, in my opinion, is a price taker in the security markets. While its control over the interest rate in the inter-bank market for reserves (Federal Funds) may be very large in the short run, it cannot and does not control interest rates in other markets, such as Treasury bills. These rates and yields are linked to world markets that are too large for the FED to control.

What does the FED control? By buying and selling securities, the FED controls the monetary base, consisting of currency plus bank reserves. It can and does inflate and deflate the size of the base. In turn, this influences growth in other monetary aggregates. These changes often have significant lagged effects on economic activity and various prices in the economy.

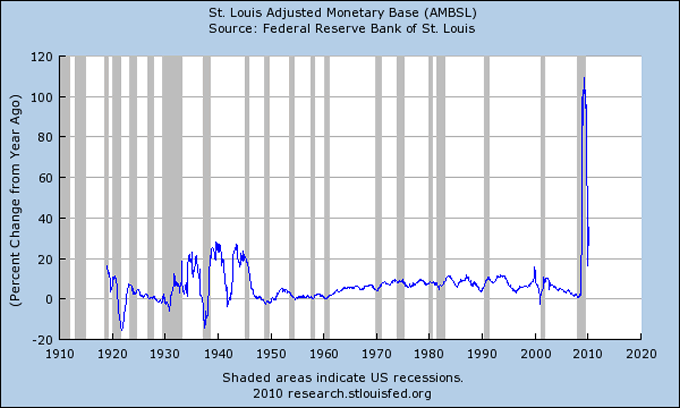

By looking at the data on the monetary base, we see the best signals of actual FED policy actions. The data series for the St. Louis adjusted monetary base (AMBSL) is my source of monetary data. The percent change from a year ago, monthly, seasonally adjusted is useful in seeing FED policy in action.

To gain some perspective on what lies ahead, it helps to look at the past. But one should not expect a duplication of the past, either in what the FED does or in what its effects are. Economic activity depends heavily on the actions of participants in the economy and they, in turn, depend heavily on their anticipations or expectations. The ways in which expectations are formed and acted upon vary at different times and epochs and with different kinds of political frameworks. This is why we cannot blindly use the past as a guide to the future when examining economic data.

To get some flavor of what goes on, let's go back to the outset of the data. The base grew at double digit rates from January 1919 to July 1919 and again from May 1920 to September 1920. In May 1928, the growth rate went negative and remained negative until June of 1929. It went negative again in December of 1929 and stayed negative until December of 1930. That deflation hit an annual rate of -5.8 percent in November 1930. In January of 1930, the FED launched an inflation that lasted until January of 1937. Double digit growth rates lasted from April 1934 to July of 1936, the highest rate reached being 23.0 percent.

After a deflationary episode in 1937-1938 that lasted 13 months, the FED resumed inflation with double digit growth in the monetary base. This lasted from May of 1938 to April of 1941, without respite. The highest rate reached was 28 percent. After another short spell of 18 months in which the base growth moderated and even went negative for 6 of those months, the double digit growth resumed. This time it lasted from November of 1942 to February of 1946, the highest annual rate being 26.9 percent.

Immediate postwar growth rates were much, much lower for the next 5 years. Indeed, growth rates in the monetary base stayed relatively moderate all the way until April of 1962 when they poked above the 4 percent level. They had stayed at or below 2.7 percent all the way from September 1953 to November of 1961.

After that, we enter a long period of high growth rates in the monetary base, usually not at double digit rates, but at rates of 6-9 percent. This period lasts from late 1961 to October of 2003. It's one very long period of inflation in the base that lasts 42 years!

This long period is evident on the graph, although it is compressed or dwarfed by what happened in the last two years.

After 2003, an interesting thing happened. As in past episodes, the FED stopped inflating and began deflating (actually merely disinflating) for an extended period of time. The drift downward in the line of growth shows that. The data tell us that the rate of growth of the base fell quite steadily to a low of 0.7 percent in April 2008. This deflation occurred in the last few years of Greenspan's reign and the first two years of Bernanke's. It's similar to other such deflations that have occurred before during the FED's history, which can readily be observed on the graph as multi-year periods in which rates of growth fall back to the zero line. In most of these cases, recessions follow, and that is what happened in 2008 and continues.

In the FED's deflationary periods (which often include merely periods of lower inflation or disinflation), the FED only needs to cease buying securities or slow the rate of purchase in order that the growth rates recede to zero. If they actually sell securities, they make the growth rate decline more steeply. If we look at the FED's balance sheet in October 2, 2003, it has Reserve Bank Credit of $727,180,000, while on April 24, 2008, it's $868,439,000. This shows what the data on growth show, namely, that the FED reduced growth rates of the base but didn't take them below zero.

The last time that the FED produced real deflation, i.e., negative rates of growth in the base, was in December 2000 and then only for two months. Before that, there is an isolated month at September 1954 in which the annual growth rate was -0.2 percent. We have to go back to 1948-1950 before we find many months of actual deflation. Although this article does not address the reasons why the FED deflates or disinflates when it does or how it determines the size of the deflation, one thing is clear, which is that the FED has not deflated in any significant and/or sustained manner in the last 60 years. At most, we observe some periods of disinflation or lower rates of growth in the monetary base.

The latest multi-year disinflation is associated, as usual, with a recession and then a renewed FED inflation or reflation, as it is often termed. This time around, the growth rates of the base have gone to historically high levels, reaching a maximum to date of 109.3 percent in May 2009. The February 2010 year over year growth rate is 35.3 percent. These growth rates are likely to keep on coming down.

The U.S. Treasury has announced that it is reinstating the Supplementary Financing Program to the tune of $200 billion. The Treasury is selling sell t-bills at a rate of $25 billion for 8 weeks and depositing the funds at its account with the FED. This lowers bank reserves by that amount. This action lowers the monetary base, until such time as the Treasury draws out the funds and spends them. The Treasury therefore has become at present a major element in the FED's exit strategy. This maneuver buys time for the FED as it seeks ways to dispose of its mortgage-backed securities. This move is costly to the Treasury, as it must pay interest on the bills it issues while it leaves funds vegetating at the FED; plus it has to keep rolling this debt over if it intends to aid the FED for longer than 8 weeks. It also uses up part of the debt limit.

Since most of the bank reserves have not been loaned, the effect on the economy is minimal. The effect on the banks is that they lose some interest paid on reserves. However, there is no guarantee that all of this will play out as a decrease in the monetary base, because the FED can always buy more securities and counteract the Treasury's action. Still, it is to be noted that in the latest reporting week, the Treasury rebuilt its balances by some $26 billion and bank reserves fell by $30.9 billion, showing the efficacy of the Treasury's action.

The Supplementary Financing Program notwithstanding, since the latest episode of disinflation has been associated with such a deep recession, it is hardly to be expected that the FED will soon bring the growth rates back to zero or even bring them to a figure within striking distance of zero. Even less likely is that they would keep the rates of growth at a low figure for a sustained period as they did between 2003 and early 2008. If they did, it would set in motion renewed recessionary shocks that the U.S. financial system is in no condition to withstand.

My bottom line is this. I do not expect a sustained Fed-caused deflation in the monetary base to occur at all, as none has occurred for 60 years. I do not even expect a sustained disinflation in the monetary base to occur as occurred between late 2003 and early 2008, for that would worsen the existing recession. I expect the growth in the base to moderate temporarily due to the Supplementary Financing Program, but at most that will do no more than bring the monetary base back to very high levels prevalent only a few months ago.

Furthermore, as time passes, the FED will not only act according to its custom but be under pressure to intensify acting in its usual inflationary mode, even barring any of many monetary emergencies that seem ever more likely to crop up now that the excesses of 60 years of excessive money and credit creation are weighing upon the economic system and weighing upon a long list of institutions.

Michael S. Rozeff [send him mail] is a retired Professor of Finance living in East Amherst, New York. He is the author of the free e-book Essays on American Empire.

© 2009 Copyright Michael S. Rozeff - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.