Wave of Unemployment in the U.S. What to Expect and What to Do- Part2

Economics / Recession 2008 - 2010 Sep 10, 2009 - 04:23 AM GMTBy: Washingtons_Blog

Continued from Part 1 here

Continued from Part 1 here

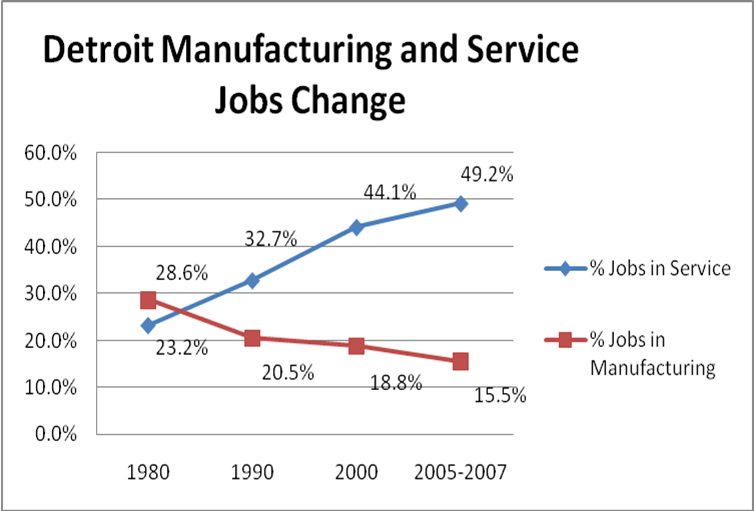

Decline in Manufacturing

As everyone knows, the manufacturing has shrunk in the United States and the service sector has grown. Even in a manufacturing center such as Detroit, manufacturing jobs have been declining for decades:

[75]

Indeed, according to professor of economics Dr. Mark J. Perry, manufacturing jobs have dropped to their lowest level since 1941, and are now below 9% of the workforce for the first time. [76]

Wayne State University's Center for Urban Studies argues:

For each job lost in the manufacturing industry, more spinoff jobs are lost than would be in other sectors. Each manufacturing job helps support a larger number of other jobs than do most other sectors. [77]

That means that the ongoing reduction in manufacturing jobs will adversely affect unemployment for the foreseeable future.

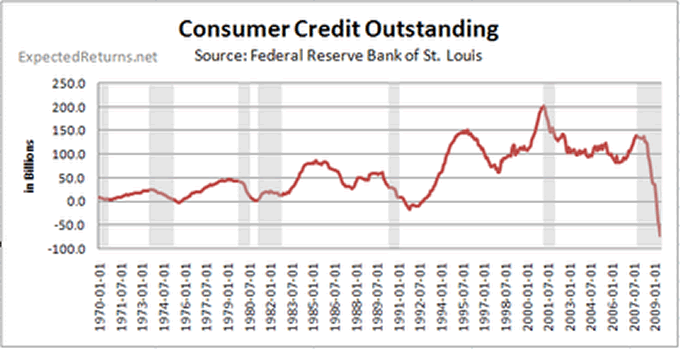

Destruction of Credit

The amount of credit outstanding has been reduced by trillions of dollars in the past year.

For example, the amount of consumer credit outstanding has plummeted:

"Will lenders deploy their new-found capital quickly, as the Treasury hopes, and unlock the flow of credit through the economy? Or will they hoard the money to protect themselves?

John A. Thain, the chief executive of Merrill Lynch, said on Thursday that banks were unlikely to act swiftly. Executives at other banks privately expressed a similar view.

'We will have the opportunity to redeploy that,' Mr. Thain said of the new capital on a telephone call with analysts. 'But at least for the next quarter, it’s just going to be a cushion.'

***

Lenders have been pulling back on credit lines for businesses, mortgages, home equity loans and credit card offers, and analysts said that trend was unlikely to be reversed by the government’s money.

Roger Freeman, an analyst at Barclays Capital, which acquired parts of the now-bankrupt Lehman Brothers last month [said] 'My expectation is it’s quarters off, not months off, before you see that capital being put to work.' ”[78]

And another New York Times article included the following quote:

“It doesn’t matter how much Hank Paulson gives us,” said an influential senior official at a big bank that received money from the government, “no one is going to lend a nickel until the economy turns.” The official added: “Who are we going to lend money to?” before repeating an old saw about banking: “Only people who don’t need it.”[79]

Reading between the lines, the bank officials are saying that they will not lend freely until the economic crisis is over.

As WLMLab Bank Loan Performance points out, outstanding loans in the United States have dropped $110 billion dollars quarter-over-quarter. [80]

McClatchy notes:

Over the course of 2008, the nation's five largest banks reduced their consumer loans by 79 percent, real estate loans by 66 percent and commercial loans by 19 percent, according to FDIC data. A wide range of credit measures, including recent FDIC data, show that lending remains depressed.[81]

Indeed, total seasonally adjusted consumer debt fell $21.55 billion, or at a 10.4% annual rate, in July 2009 alone. credit-card debt fell $6.11 billion, or 8.5%, to $905.58 billion. This is the record 11th straight monthly drop in credit card debt. Non-revolving credit, such as auto loans, personal loans and student loans fell a record $15.44 billion or 11.7% to $1.57 trillion [82]

In addition, the securitization market has largely collapsed, which in turn has destroyed a large proportion of the world's credit. As noted in an article in the Washington Times:

“Before last fall’s financial crisis, banks provided only $8 trillion of the roughly $25 trillion in loans outstanding in the United States, while traditional bond markets provided another $7 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve. The largest share of the borrowed funds - $10 trillion - came from securitized loan markets that barely existed two decades ago. . . .

Mr. Regalia [chief economist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce] said ... 70 percent of the system isn’t there anymore,’ he said.”[83]

The reason that seventy percent of the system "isn’t there anymore" is because the traditional bond markets and securitized loan markets (part of the "shadow banking system") have dried up. As the Washington Times article notes:

“Congress’ demand that banks fill in for collapsed securities markets poses a dilemma for the banks, not only because most do not have the capacity to ramp up to such large-scale lending quickly. The securitized loan markets provided an essential part of the machinery that enabled banks to lend in the first place. By selling most of their portfolios of mortgages, business and consumer loans to investors, banks in the past freed up money to make new loans. . . .

“The market for pooled subprime loans, known as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collapsed at the end of 2007 and, by most accounts, will never come back. Because of the surging defaults on subprime and other exotic mortgages, investors have shied away from buying the loans, forcing banks and Wall Street firms to hold them on their books and take the losses.”

Senior economic adviser for UBS Investment Bank, George Magnus, confirms:

The restoration of normal credit creation should not be expected, until the economy has adjusted to the disappearance of shadow bank credit, and until banks have created the capacity to resume lending to creditworthy borrowers. This is still about capital adequacy, where better signs of organic capital creation are welcome. More importantly now though, it is about poor asset quality, especially as defaults and loan losses rise into 2010 from already elevated levels.[84]

And McClatchy writes:

The foundation of U.S. credit expansion for the past 20 years is in ruin. Since the 1980s, banks haven't kept loans on their balance sheets; instead, they sold them into a secondary market, where they were pooled for sale to investors as securities. The process, called securitization, fueled a rapid expansion of credit to consumers and businesses. By passing their loans on to investors, banks were freed to lend more.

Today, securitization is all but dead. Investors have little appetite for risky securities. Few buyers want a security based on pools of mortgages, car loans, student loans and the like.

"The basis of revival of the system along the line of what previously existed doesn't exist. The foundation that was supposed to be there for the revival (of the economy) . . . got washed away," [economist James K.] Galbraith said.

Unless and until securitization rebounds, it will be hard for banks to resume robust lending because they're stuck with loans on their books.[85]

Not only has the supply of credit been destroyed, but the demand for many types of loans - such as commercial real estate loans - is also drying up.[86]

So there is simply much less credit flowing through the economic system than there was prior to 2007.

The New Normal - Lower Economic Activity

As chief economist for the International Monetary Fund, Olivier Blanchard, said:

This recession has been so destructive that "we may not go back to the old growth path ... potential output may be lower than it was before the crisis." [87]

All of the above trends force many economists to conclude that economic activity as a whole will be lower for many, many years. In other words, they say that "The New Normal" will be a much lower level for the economy.

Pimco CEO Mohamed El-Erian says elevated unemployment and record wealth destruction will keep growth at 2 percent or less for years. [88]

As Bloomberg writes:

The New Normal theory predicts that the recession will leave unemployment, forecast to reach 10 percent for the first time since 1983 early next year, higher for years. [89]

Indeed, the "overhang" of inventory [90]- that is, the inventory of unsold goods - in everything from housing [91 and 92] to cars [93] to consumer electronics [94] means that the newly reduced consumer demand is meeting up with very high levels of supply. This is a recipe for unemployment.

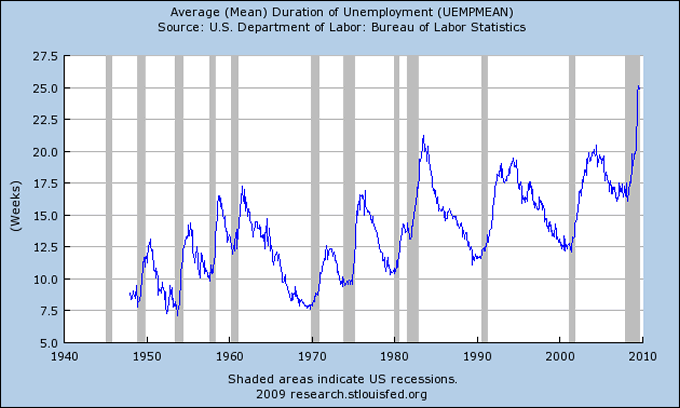

Many economists also point out that the length of time people are remaining unemployed is skyrocketing. As the Washington Post notes:

Another disturbing development was that the number of people out of work for 27 weeks or longer reached a record 5 million, accounting for a third of the unemployed. That suggests to some economists that those job losses were caused by structural changes in the economy and that many of those people won't be called back to work once the economy picks up. The longer people are out of work, the harder it becomes for them to find jobs and the more likely they are to exhaust savings or lose their homes to foreclosure. [95]

The following chart from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank shows that people are staying unemployed much longer than they have in any previous economic downturn since 1950:

[96]

As David Rosenberg writes:

The number of people not on temporary layoff surged 220,000 in August and the level continues to reach new highs, now at 8.1 million. This accounts for 53.9% of the unemployed — again a record high — and this is a proxy for permanent job loss, in other words, these jobs are not coming back. Against that backdrop, the number of people who have been looking for a job for at least six months with no success rose a further half-percent in August, to stand at 5 million — the long-term unemployed now represent a record 33% of the total pool of joblessness. [97]

[98: for graphical updates on the state of the economy, see charts from the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank posted at http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/data/updates/index.cfm?DCS.nav=Local]

Another Trend: Increased Productivity Means Less Jobs

All of the aforementioned economic trends point to lower levels of job creation, and thus higher unemployment.

In addition, the chief economist for MarketWatch, Distinguished Scholar of Economics at Dowling College (Irwin Kellner) points out that worker productivity is rising, and that increased worker productivity means less new people will be hired. [99]

Other Theories Regarding the Causes of Unemployment

The main cause of unemployment today is the economic crisis. For example, a report from the the National Industrial Conference Board pointed out in 1922 stated the obvious: depressions increase unemployment. [100]

The report also points out that seasonal variations, "immigration and tariff policies and international relationship" can affect unemployment figures. [101]

In fact, economists from different schools of thought ascribe different causes to unemployment. For example:

Keynesian economics emphasizes unemployment resulting from insufficient effective demand for goods and services in the economy (cyclical unemployment). Others point to structural problems, inefficiencies, inherent in labour markets (structural unemployment). Classical or neoclassical economics tends to reject these explanations, and focuses more on rigidities imposed on the labor market from the outside, such as minimum wage laws, taxes, and other regulations that may discourage the hiring of workers (classical unemployment). Yet others see unemployment as largely due to voluntary choices by the unemployed (frictional unemployment). Alternatively, some blame unemployment on disruptive technologies or Globalisation.

[102 and 103]

For example, many Americans believe that globalization has increased unemployment because "American jobs" have moved abroad. Certainly, the American government has encouraged multinational corporations based in the U.S. to move jobs overseas. But quick fixes may lead to new problems. For example, a new American protectionism could stifle trade, further weakening the American economy.

Similarly, some economists believe that inflation decreases unemployment. However, that is only true where the workers drastically underestimate the extent to which higher prices are decreasing the real value of their wages. Indeed, as the Cato Institute notes:

This reduction in unemployment cannot occur unless workers systematically underestimate the inflation rate. When workers are aware of the inflation rate and, for example, have their pay adjusted according to the cost of living, they will interpret wages properly and not be misled into thinking that a normal wage offer is a relatively high wage offer.

Rather than merely failing to decrease unemployment, inflation may actually increase the unemployment rate. Frequent concomitants of inflation, such as high interest rates and volatility and uncertainty in the financial and product markets, increase the risks inherent in business operations and thereby discourage the expansion of firms and the creation of jobs. [104]

Therefore, many "quick fixes" for unemployment may actually do more harm than good.

Isn't the Government Helping to Reduce Unemployment?

The government has committed to give trillions to the financial industry. President Obama's stimulus bill was $787 billion, which is less than a tenth of the money pledged to the banks and the financial system. [105]

Of the $787 billion, little more than perhaps 10% has been spent as of this writing. [106]

The Government Accountability Office says that the $787 billion stimulus package is not being used for stimulus. [107] Instead, the states are in such dire financial straights that the stimulus money is instead being used to "cushion" state budgets, prevent teacher layoffs, make more Medicaid payments and head off other fiscal problems. So even the money which is actually earmarked to help the states stimulate their economies is not being used for that purpose.

Indeed, much of the $787 billion was earmarked pork [108], not for anything which could actually stimulate the economy. [109]

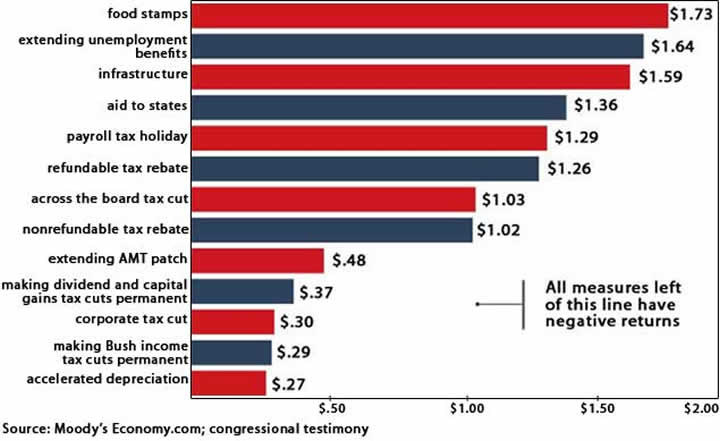

Mark Zandi - chief economist for Moody's - has calculated which stimulus programs give the most bang for the buck in terms of the economy:

But very little of the stimulus funds are actually going to high-value stimulus projects.

Indeed, as the Los Angeles Times points out:

Critics say the [stimulus money reaching California] is being used for projects that would have been built anyway, instead of on ways to change how Californians live. Case in point: Army latrines, not high-speed rail.

***

Critics say those aren't the types of projects with lasting effects on the economy.

"Whether it's talking about building a new [military] hospital or bachelor's quarters, there isn't that return on investment that you'd find on something that increases efficiency like a road or transit project," said Ellis of Taxpayers for Common Sense.

Job creation is another question. A recent survey by the Associated General Contractors of America found that slightly more than one-third of the companies awarded stimulus projects planned to hire new employees. But about one-third of the companies that weren't awarded stimulus projects also planned to hire new employees.

"While the construction portion of the stimulus is having an impact, it is far from delivering its full promise and potential," said Stephen E. Sandherr, chief executive of the contractors group.

It's unclear how many jobs will be created through the Defense Department projects. Most of the construction jobs are awarded through multiple award contracts, in which the department guarantees a minimum amount of business to certain contractors, and lets only those contractors bid on projects.

That means many of the contractors working on stimulus projects already have been busy at work on government projects.even the stimulus money which is being spent [111]David Rosenberg writes:

Our advice to the Obama team would be to create and nurture a fiscal backdrop that tackles this jobs crisis with some permanent solutions rather than recurring populist short-term fiscal goodies that are only inducing households to add to their burdensome debt loads with no long-term multiplier impacts. The problem is not that we have an insufficient number of vehicles on the road or homes on the market; the problem is that we have insufficient labour demand.[112]

Donald W. Riegle Jr. - former chair of the Senate Banking Committee from 1989 to 1994 - wrote (along with the former CEO of AT&T Broadband and the international president of the United Steelworkers union):

It's almost as if the administration is opting for a rose-colored-glasses PR strategy rather than taking a hard-nose look at actual consumer and employment figures and their trends, and modifying its economic policies accordingly.[113]

How Much Unemployment Do We Want?

On the one end of the spectrum, Article 23 of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares:

Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.[114]

In other words, the U.N. says that there should be essentially no unemployment for those who wish to work.

On the other end of the spectrum, some people - who make a lot of money during periods where the condition lead to high levels of unemployment - are comfortable with unemployment percentages reaching those in the Great Depression.

Societies should decide for themselves what level of unemployment they consider acceptable, and then demand policies which will accomplish that goal to the greatest extent possible. As discussed above, there are many factors which affect employment levels, and so solutions are complicated.

However, without an open and visible public policy debate about the issue, unemployment levels will either remain second order affects of policy choices concerning other elements of the economy, or will be decided behind closed doors by decision-makers who may or may not have the best public interest in mind.

Public Funding

As the above facts show, unemployment is a very serious problem in the United states, and world-wide. The policy responses of the U.S. and other Western governments has not been working. As discussed above, there is no simple solution.

Senator Riegle recommends a 4-part prescription, including:

Ensure that loans and credit facilities are readily available to the nation's small and medium size businesses and manufacturers.

Many of the top economists argue that we need to break up the giant banks which are insolvent in order to save the economy.[115] Fortune[116], BusinessWeek[117] and Federal Reserve governor Daniel K. Tarullo[118] have pointed out that breaking up the largest, insolvent banks would allow more competition from small to mid-size banks, and that such banks may actually make more loans to small businesses. More loans to small businesses would lead to more employment by those many small businesses.

In addition, the U.S. has largely been financing job creation for ten years. Specifically, as the chief economist for BusinessWeek, Michael Mandel, points out, public spending has accounted for virtually all new job creation in the past 1o years:

Private sector job growth was almost non-existent over the past ten years. Take a look at this horrifying chart:

Between May 1999 and May 2009, employment in the private sector sector only rose by 1.1%, by far the lowest 10-year increase in the post-depression period.

It’s impossible to overstate how bad this is. Basically speaking, the private sector job machine has almost completely stalled over the past ten years. Take a look at this chart:

Over the past 10 years, the private sector has generated roughly 1.1 million additional jobs, or about 100K per year. The public sector created about 2.4 million jobs.

But even that gives the private sector too much credit. Remember that the private sector includes health care, social assistance, and education, all areas which receive a lot of government support.

***

Most of the industries which had positive job growth over the past ten years were in the HealthEdGov sector. In fact, financial job growth was nearly nonexistent once we take out the health insurers.

Let me finish with a final chart.

Without a decade of growing government support from rising health and education spending and soaring budget deficits, the labor market would have been flat on its back. [119]

Raw Story argues that the U.S. is building a largely military economy:

The use of the military-industrial complex as a quick, if dubious, way of jump-starting the economy is nothing new, but what is amazing is the divergence between the military economy and the civilian economy, as shown by this New York Times chart.

In the past nine years, non-industrial production in the US has declined by some 19 percent. It took about four years for manufacturing to return to levels seen before the 2001 recession -- and all those gains were wiped out in the current recession.

By contrast, military manufacturing is now 123 percent greater than it was in 2000 -- it has more than doubled while the rest of the manufacturing sector has been shrinking...

It's important to note the trajectory -- the military economy is nearly three times as large, proportionally to the rest of the economy, as it was at the beginning of the Bush administration. And it is the only manufacturing sector showing any growth. Extrapolate that trend, and what do you get?

The change in leadership in Washington does not appear to be abating that trend...[120]So most of the job creation has been by the public sector. But because the job creation has been financed with loans from China and private banks, trillions in unnecessary interest charges have been incurred by the U.S.

Former Washington Post editor and author of one of the leading books on the Federal Reserve, William Greider, points out that governments actually have the power to create money and credit themselves, instead of borrowing it at interest from private banks:

If Congress chooses to take charge of its constitutional duty, it could similarly use greenback currency created by the Federal Reserve as a legitimate channel for financing important public projects--like sorely needed improvements to the nation's infrastructure. Obviously, this has to be done carefully and responsibly, limited to normal expansion of the money supply and used only for projects that truly benefit the entire nation (lest it lead to inflation)...

This approach speaks to the contradiction House Speaker Pelosi pointed out when she asked why the Fed has limitless money to spend however it sees fit. Instead of borrowing the money to pay for the new rail system, the government financing would draw on the public's money-creation process--just as Lincoln did and Bernanke is now doing.[121]By creating the credit itself - instead of borrowing from private banks and foreign nations - the American government could finance the creation of new jobs without incurring huge interest charges owed to the private banks and foreign countries which lent America the money. In other words, the U.S. government would itself create the new credit, just as Lincoln did to finance the civil war.

By financing new projects with credit created by the government itself, America might be able to pick itself up by its bootstraps and put its people back to work.

The same may be true for other countries as well.

Global Research Articles by Washington's Blog

© Copyright Washingtons Blog, Global Research, 2009

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Centre for Research on Globalization. The contents of this article are of sole responsibility of the author(s). The Centre for Research on Globalization will not be responsible or liable for any inaccurate or incorrect statements contained in this article.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.