The Case for Economic Depression, Credit Destruction

Economics / Great Depression II Jul 01, 2009 - 08:02 AM GMTBy: Moses_Kim

Periodically in history, the expansion of credit creates the illusion of prosperity that ends in the inevitable bust. When John Law seemingly struck gold by introducing fiat currency in France, he was hailed as a financial genius. Four years and an economic collapse later, he was humiliated, shunned, and exiled.

Periodically in history, the expansion of credit creates the illusion of prosperity that ends in the inevitable bust. When John Law seemingly struck gold by introducing fiat currency in France, he was hailed as a financial genius. Four years and an economic collapse later, he was humiliated, shunned, and exiled.

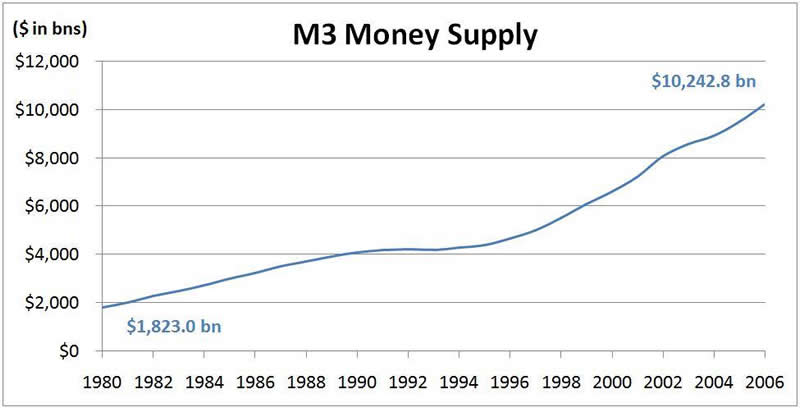

John Law is notoriously known as the world's first central banker. Over the years, the Federal Reserve has fine-tuned the process of credit creation in the image of John Law. Under Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve drastically lowered interest rates, which effectively meant that the money supply increased. With the help of an accommodating Federal Reserve, M3 money supply exploded.

This money found its way to real estate and stocks, fuelling a consumption binge that led to massive current account deficits. In a functioning gold standard, current account imbalances self-correct. However, in our fiat-based system- with the dollar as the reserve currency - current account deficits persist as foreigners use their acquired dollars to purchase Treasuries. This sterilization process holds inflation in check, while suppressing interest rates. Crudely, massive current account deficits served to reinforce the creation of credit and perpetuate the historic debt bubble.

Unfortunately, the bubble has started to deflate. Thus far, I believe we have only seen the early effects of credit destruction. To see how this depression will potentially play out, we will have to turn to the Great Depression and Japan's "Lost Decade" for guidance.

The Great Depression saw an enormous expansion in credit that led to the debt driven "Roaring Twenties". People were similarly under the illusion that a new era of prosperity was at hand, regardless of increasing debt obligations. The bubble eventually popped, and excessive margin on stocks led to the stock market collapse in 1929. Massive debt liquidation hindered economic growth for over a decade.

The current debt crisis dwarfs that of the Great Depression for many reasons. To begin, indebtedness is more widespread, spanning the government, consumer, and corporate sectors; whereas, during the Great Depression, debt was isolated to the government sector. The magnitude of debt is also greater. At the onset of the Great Depression, interest bearing debt was 170% of GDP; in 2008, total interest bearing debt reached 350% of GDP. This monumental debt burden doesn't even take into account unregulated derivatives, which are perhaps the biggest threat to our financial system. Warren Buffett called derivatives "weapons of financial mass destruction", and indeed they are. The collapse of Lehman almost brought down our whole financial edifice. The truth is, Lehman was a small player in the derivatives game. Anyone who thinks the threat of systematic collapse has been averted is underestimating the potential effect of over 500 trillion dollars in derivatives imploding as counter parties default.

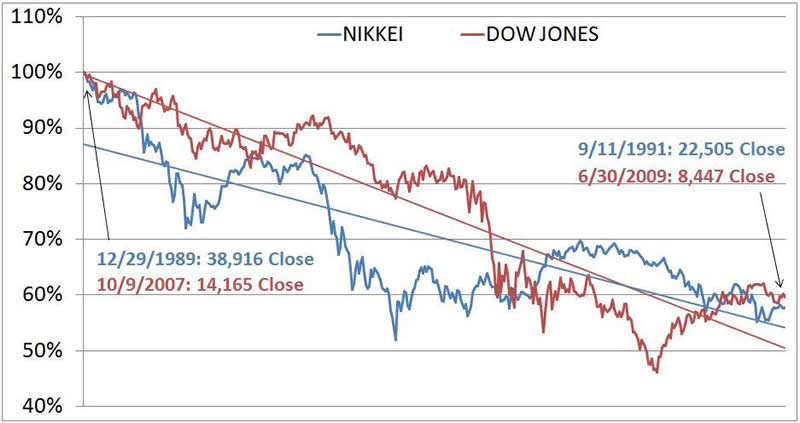

The "Lost Decade" in Japan provides another illustration of a collapsing debt bubble. The level of total household debt as a percentage of disposable income reached 130% prior to Japan's collapse. U.S. households reached similar levels of indebtedness last year before the start of the current crisis. Using stocks as a means of comparison, we can expect a downturn in the Dow in line with the Nikkei's 80% collapse. Although this may seem unfathomable, the Dow is certainly pointing to this possibility.

Like all bubbles, the U.S. debt bubble is ending. The recent 200 basis point rise in Treasury yields evidences our deteriorating financial position. Ultimately, rising yields are a reflection of an imbalance between supply and demand. Foreign governments, most notably the Chinese, are selling our long-term debt in favor of hard assets. This secular trend will prevail as long as we continue to run massive budget deficits and attempt to make up the difference through the printing press.

Economists and media pundits who are calling for an end to the "recession" this year plainly do not understand the nature of credit in our system. The sheer magnitude of credit destruction occurring right now is depressionary. The return to growth will be a long and painful process exacerbated by negative demographic trends. I will discuss the impact of demographics in greater detail in Part 3 of "The Case for Depression."

By Moses Kim

http://expectedreturns.blogspot.com/

Graduate of Columbia University with a B.A. in History. Student of the markets focused on long-term economic trends. I believe the markets are inefficient, and that these inefficiencies can be exploited to attain profitable returns.

© 2009 Copyright Moses Kim - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.