U-Turn or Perfect Storm? Globalization a Decade after the Financial Crisis

Economics / Global Economy Sep 10, 2018 - 08:20 AM GMTBy: Dan_Steinbock

A decade ago, globalization peaked. Today, it remains in the doldrums. Consequently, the Trump trade wars take place at a historical moment, when globalization may further stagnate or even fall apart.

A decade ago, globalization peaked. Today, it remains in the doldrums. Consequently, the Trump trade wars take place at a historical moment, when globalization may further stagnate or even fall apart.

On Friday September 7, President Donald Trump threatened to impose tariffs on $267 billion in Chinese goods, on top of the additional $200 billion that he said will likely be hit with import taxes in a matter of days.

If the tariff stakes would increase close to $500 billion, it could penalize Chinese GDP by 1.0%, but the US GDP, which is relatively more vulnerable, would suffer a net impact of 2.0% of GDP.

Worse, a full trade war would penalize global confidence, which could unsettle key stock indexes. The consequent uncertainty would lead to further downgrades of countries’ economic outlook. Global growth would suffer collateral damage. And as credit would take a hit, financial conditions in the West could deteriorate, and so would trade in the East.

If Trump remains loyal to his trade pledges, following China he would target other major economies that have a significant trade surplus with the U.S., including Germany, Italy and the EU, Japan and South Korea, Mexico and Canada and, over time, Vietnam and India.

If the Trump administration would expand its trade war as it has promised, it would achieve a perfect reversal of decades of postwar globalization in just months – and it would pave way to a perfect storm in the global economy.

Globalization at crossroads

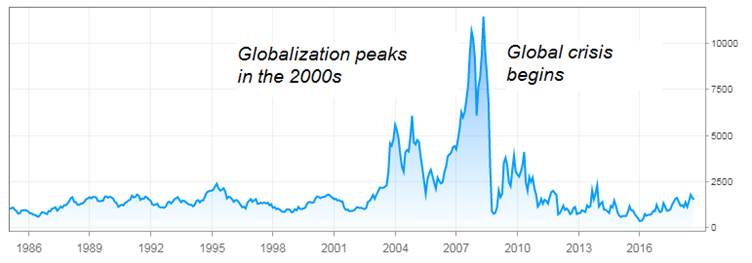

At the peak of globalization, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) was often used as a barometer for international commodity trade. The index soared to a record high in May 2008 reaching 11,793 points. But as the financial crisis spread in the advanced West, the BDI plunged by 94% to 663 points.

Even today, the BDI remains only around 1,500, some 90% below its peak, despite soaring financial markets (Figure).

Figure The Baltic Dry Index, 1986-2018

While the BDI can serve as a short hand for international trade, broader measures of global economic engagement offer equally dire visions.

Global economic integration is usually measured by world trade, investment, and migration. By the 1870s, capital and trade flows rapidly increased, driven by falling transport costs. But the first wave of globalization in the modern era was reversed by the retreat of the U.S. and Europe into protectionism between 1914 and 1945.

After World War II, trade barriers came down, and transport costs continued to fall. As foreign direct investment (FDI) and international trade returned to the pre-1914 levels, globalization was fueled by Western Europe and the rise of Japan. This second wave of globalization benefited mainly the advanced economies.

Following 1980 many developing countries broke into world markets for manufactured goods and services, while they were also able to attract foreign capital, thanks to offshoring in the West. This era of globalization peaked between China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and the global financial crisis in 2008.

After the global crisis, China and large emerging economies fueled the international economy, which was thus spared from a global depression. But as G20 cooperation has dimmed, so have global growth prospects.

Falling world investment

Before the global crisis, world investment soared to almost $2 trillion. A year or two ago, the UN predicted that global FDI flows were projected to resume growth in 2017 and to surpass $1.8 trillion in 2018. In contrast, I predicted that the improvement was unlikely and that world investment would either continue to stagnate or worse.

So what actually happened? Well, according to the most recent UN data, global flows of foreign direct investment fell by a whopping 23% in 2017. Cross-border investment in developed and transition economies dropped sharply, while growth was near zero in developing economies.

In effect, global FDI flows fell to $1.43 trillion – that is almost 20% below the pre-crisis peak around 2007-8. In turn, FDI flows to developing economies remained stable at $671 billion, seeing no recovery following the 10% drop in 2016.

This negative trend is not just a long-term concern for policymakers worldwide; it should be an alarm bell, especially as US rate hikes are likely to dampen the projections of many emerging economies and the collateral damage associated with US trade wars is likely to spread in global economy.

Undermined world trade recovery

In 2017, world merchandise trade recorded its strongest growth in six years. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the ratio of trade growth to GDP growth returned to its historic average of 1.5, far above the 1.0 ratio recorded in the years following the 2008 financial crisis.

"Trade growth in 2017 was the strongest since 2011,” said WTO Director-General Roberto Azevêdo in his opening message. "If we are to avoid this strong performance being compromised by a further escalation in tensions, we must seek to further enhance global cooperation."

Yet, that is precisely what is unlikely to happen in 2018. Azevêdo wrote his message before Trump’s tariff warnings took effect.

Historically, it may be useful to recall that, about a decade ago in July 2008 WTO then-Director-General Pascal Lamy declared that there was “unqualified public support for globalization.” Yet by that fall, trade depression halted most containers worldwide.

It does not follow that history will repeat itself, but it does rhyme. Trump’s tariff wars are penalizing a trade recovery that took a decade to materialize.

The slump of global finance

The soaring stock equity markets in the United States reflect less the strong fundamentals of the U.S. economy (America’s sovereign debt exceeds 106% of its GDP) than wishful thinking about U.S. leadership in the 21st century. Following the global financial crisis, there has been a dramatic fall in global finance as well.

Global debt has continued to swell since the crisis but has remained stable relative to world GDP since 2014; that is, at 169% of global GDP.

Indeed, gross cross-border capital flows-annual flows of FDI, purchases of bonds and equities, lending and other investment-have shrunk by -53% in absolute terms, returning to the level of global flows as a share of GDP last seen in the early 2000s.

The sharp contraction in gross cross-border lending and other investment flows explain half of the decline, and Eurozone banks are leading the retreat.

From geopolitical friction to migration crises

Since the advanced West subjected migration to greater control in the early 20th century, global migration—the third leg of globalization—has shrunk dramatically. Yet, the number of globally displaced people has surged.

Wars, other violence and persecution drove worldwide forced displacement to a new high in 2017 for the fifth year in a row. Overwhelmingly it is developing countries that are most affected. According to the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, 69 million people were displaced as of the end of 2017. Among them were 16.2 million people who became displaced during 2017. In other words, about 45,000 people are being displaced each day.

This represents the greatest global forced displacement since 1945.

As evidenced by recent migrant crises in Western Europe and Trump’s intent to build a wall against Mexico, sentiments against migration are hardening – precisely at the time when skill-based immigration would be vital to the future of advanced economies, which are rapidly aging and stagnating.

Beware of rising risks

So these are the prospects of globalization today. International commodity trade is now where it first was in the early 1990s, according to the Baltic Dry Index. Global investment is plunging. Trump’s tariff wars have potential to undermine a global trade recovery. Global financial flows are now where they first were 10-15 years ago.

The only highs in recent globalization stem from the surge of the number of globally displaced people.

As the IMF has warned, the ongoing cyclical recovery in global growth prospects is likely to wind down in a year or two. Thanks to the Trump administration’s tariff wars, the day of reckoning may take place much sooner.

Of course, globalization is no panacea. It has always been accompanied with winners and losers.

Yet, in the current status quo, when the growth drivers in major advanced economies are amid secular stagnation and consequently growth prospects are decelerating in emerging economies, external growth drivers are desperately needed.

Nevertheless – so it seems now – it is precisely those forces of world investment, trade, finance, and migration that are currently being undermined.

Dr Steinbock is the founder of the Difference Group and has served as the research director at the India, China, and America Institute (USA) and a visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more information, see http://www.differencegroup.net/

© 2018 Copyright Dan Steinbock - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

Dan Steinbock Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.